The Aussie towns destroyed by China’s economic slowdown

THESE Aussie towns were booming. But now, they’re plagued by closed businesses, plummeting property prices and fleeing residents.

A SLOWDOWN in China and shrinkage in the consumption of coal are tearing holes in the fabric of once-booming mining towns in Queensland’s Bowen Basin.

At the peak of the coal boom in 2011, the Bowen Basin boasted 48 operational coal mines and more than 50 mining projects.

Driven by rocketing demand from Asia, coal and iron-ore insulated the country from the worst of the GFC, and temporarily turned Australia into the world’s largest exporter of coal. Japan is the biggest buyer, with China in second place buying another 23 per cent. As the world’s largest importer and consumer of coal, China and its promise of perpetual economic growth was the linchpin upon which the Australian coal industry pegged its prosperity.

By 2012, oversupply of the commodity, coupled with Chinese efforts to diminish dependence on the most polluting of all fossil fuels saw coal prices start to head south. Last month, thermal coal fell to $73 per tonne (compared to $166 per tonne in 2011), while the commodity price for a tonne of metallurgic coal fell to $135, from $380.

Coal’s free fall has sent shock waves through the Bowen Basin. Half a dozen mines have been closed, a third of those that remain operational are running at losses and more than 1,200 mining jobs were axed last year alone. And new mine closures and job losses loom heavily on the Central Queensland’s blood-red horizon.

SHOCK AND AWE

“The future is not positive — a lot of people have taken their kids out of the school here and relocated to the coast,” says Terry Benson, an unemployed mine worker at Dysart, a community established in 1973 for workers at the nearby Norwich Park and Saraji coal mines. “When I go to the shopping centre on Saturday morning, the place is deserted. Half the shops are closed.”

Dysart made headlines in 2011 when the Real Estate Institute of Queensland reported it had the most expensive medium rent in the state at $1,200 per dwelling per week. But the market hit hard times in 2012 when the BHP Billiton Mitsubishi Alliance closed Norwich Park and sacked the entire workforce of 490. When another 240 jobs were cut at nearby Saraji coal mine last September, the market all but collapsed. Today, asking prices for three-bedroom homes in Dysart start at $150 a week.

Things aren’t much better in Moranbah, the basin’s largest mining town. Three years ago, old weatherboard homes in Moranbah fetched rents as high as $2,000 a week, their driveways flush with speedboats, race cars, dirt bikes and Harley Davidsons. Today many of those trophies of success and excess are parked on the nature strip on Mills Avenue — Moranbah’s main street — with telltale for-sale signs sticky taped to their windscreens.

“In 2011 more than 200 properties changed hands in this town,” says principal of AH Realty, Annemarie Haywood. “People were paying up to $1 million for houses that didn’t even have grass in the backyard. Now those investors are desperate to sell before the bank takes their properties. We have mortgagee sales every second week in Moranbah.

“This town has seen so much pain. There is not one business in town that is not struggling. Truck drivers during the boom were making $135,000 a year. Now, if they are lucky enough to have jobs, they work for half that much.”

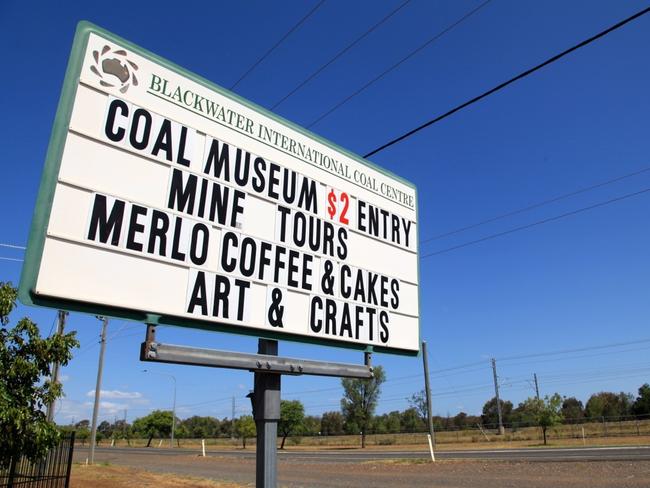

Then there’s Blackwater, which is ground zero of the Chinese economic slowdown in Central Queensland. It’s a fly-bit, dust-covered semi-ghost-town where storefronts are boarded up with metal grates and weeds grow from plots earmarked for long-forgot housing estates. Blistering heat adds a near absolute sense of desolation to the place.

“Things are terrible now,” says Linda O’Liffe, a lifelong resident of Blackwater who tries to sell tea cosies and coal figurines made in China from a booth inside The Australian Coal Museum. “We’ve had downturns in the past but they usually lasted 12 months or less,” she says, peering around an empty lobby. “This is the longest downturn I’ve ever seen.”

THE BLAME GAME

Moranbah is also where Kent Hagarty of ABC Drilling and Mining Products got his start as a driller in the mines in the 1990s. “It was the biggest boom we’ve ever seen and probably will ever see,” he says. “Everyone in drilling geared up,” he says.

But with exploration work in coal now stagnant, Hagarty has had to retool his rigs and go searching for other minerals in the basin — gold, nickel and copper. He’s also had to sack 20% of his workforce.

He adds: “All this bad news definitely puts you on edge. You just got to keep thinking that it’ll pass, that demand for coal will come back. The problem is there’s a glut because coal mines popped up everywhere when the price was up. I think there could have been more regulation to prevent that from happening.”

But intervention by the Australian Government would have been futile according to Peter Maguire, mayor of Emerald, a 19th century railway town founded in agriculture. Emerald’s economy is tied to mining and its townspeople have not proven immune to coal’s downturn. In an industrial estate on the outskirt of town, there are rows of gargantuan Kamatsu mining trucks with payload capacities exceeding 300 tons, as dormant as the speedboats on Moranbah’s Mills Avenue.

“If you’re looking for someone to blame there are three different levels of government,” Maguire says. “We don’t have the answers at the local level of government and the state and federal governments are not spending any new money on infrastructure right now. The high value of the Australia dollar is more to blame than anything else.”

READING TEA LEAVES

Global head of economics at Macquarie Bank Richard Gibbs says Australia’s coal industry is facing a double whammy because supply is increasing after a decade of heavy investment while demand is shifting down.

“The supply curve has a very long gestation period, is very expensive to scale down and cannot be finetuned as much as mining companies would like to,” Gibbs explains. “Ergo you’ll always get these downward parts of the economic cycle where mining companies overshoot the mark. So the million-dollar question is, is the downshift in demand terminal? I think it is.”

Gibbs is adding his voice to the chorus of commentators discounting Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s claim that coal is an “essential part” of our economic future. “I think we’re moving towards a coal-free future and what we’re seeing in the Bowen Basin is material evidence of that.”

A new Chinese law banning the use of coal with high levels of sulphur and ash in areas around its largest cities to counter air pollution backs Gibbs up. The Bureau of Resource Economics warns the new law alone could reduce Australia’s thermal coal exports to China by one sixth. Coupled with a pledge to produce 15 per cent of its power from renewables by 2020 and advancements in micro nuclear reactors, China is closely approaching an infliction point known as peak-coal where long-term structural shift away from coal as a commodity sets in.

But the long-term fundamentals of Australian coal exports remain sound according to the all-powerful peak body the Minerals Council of Australia. “You only need to look at demand,” says executive director for coal Greg Evans. “China will continue to be overly reliant on coal for base load power supply and steel production. China is only part of the story. Japan is still the leading market and we have long-term stable markets in South Korea and Taiwan.”

The council backs its stance with a flurry of theories and figures, starting with research by The International Energy Association that global coal trade will increase 40% by 2040 and Australia will capture the lion’s share of growth. So there is reason to hope mining communities in the Bowen Basin may return from the dead.

Yet hope left town long ago for people like Terry Benson in Dysart, who wiles away his time at the Jolly Collier Hotel, and Linda O’Liffe, the dame of Blackwater. “Going back a few years, that highway outside was buzzing with cars and trucks and trains,” she says. At night, you’d see a long line of headlights. Now even the town is pitch black at night because half the houses are empty. It’s like things were when I was a kid here in the 1950s, before mining started.”