China vowed to reduce steel output but hasn’t – is it part of a sinister plan?

China has said one thing, but is doing something different – spelling good news for Australia. But it could all be part of a sinister plan.

Amid a backdrop of rising tensions between Beijing and Canberra, the price of iron ore has continued to skyrocket in recent weeks and currently sits at an all-time high.

Despite Beijing’s various threats and trade actions against all manner of Aussie industries from shellfish to barley, this single factor has resulted in trade flows between Australia and China continuing to reach record highs.

This really is quite strange given the commentary that has been coming out of Beijing in the past six months.

China vowed to reduce steel output

At the end of last year, China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) stated that China “must resolutely” reduce steel output to below 2020 levels of production.

Unsurprisingly at the time, the price of iron ore dropped more than 5 per cent, on the expectation from commodity traders that steel production restrictions would be put in place by Beijing to reduce steel output.

Then at the start of April, Chinese industry regulators and the Ministry of Industry once again reaffirmed that annual steel production would be cut. They went on to state that they would jointly investigate excess steel production that went against Beijing’s order.

In reality, things couldn’t be more different.

RELATED: ASX sets 14-day high after iron ore surge

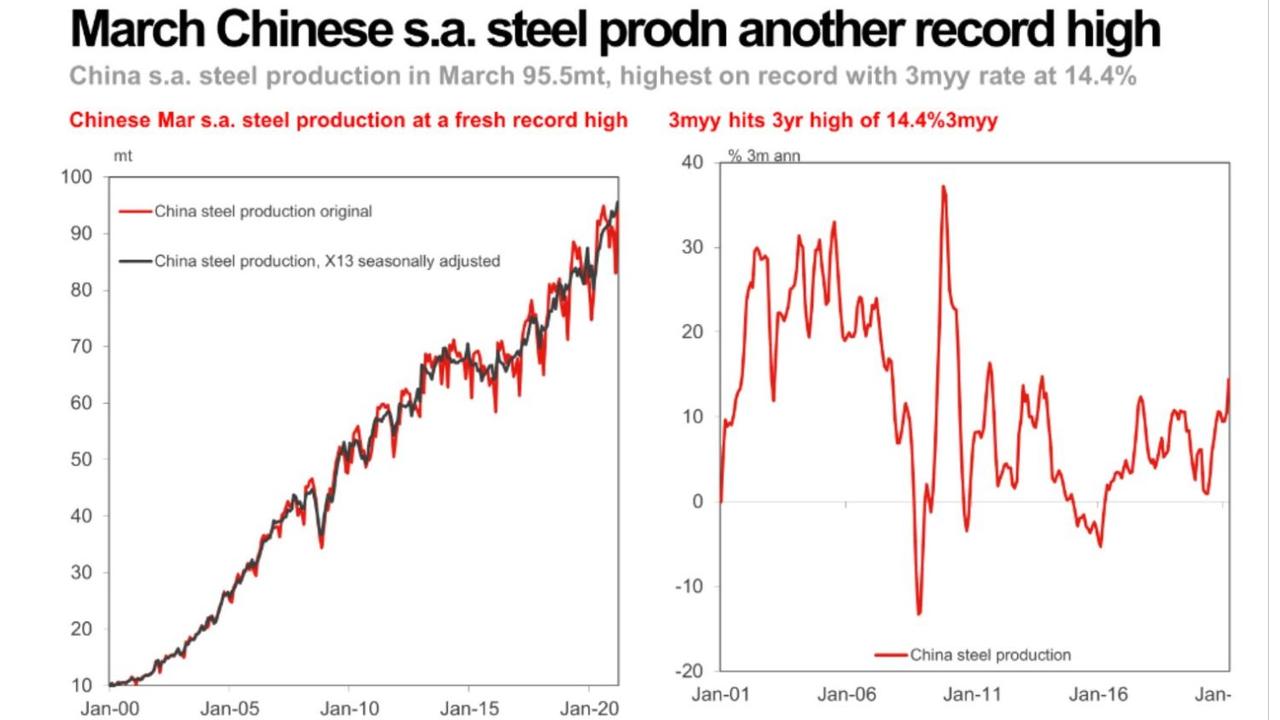

According to figures from Bloomberg and Westpac, Chinese steel production is actually at a record high. More than that, steel production is currently growing at 14.4 per cent on an annualised three-month basis.

As a result, China’s reliance on Australia for iron ore has only continued to grow in recent months, as the reality of a tight supply of ore in the global market continues to bite.

Needless to say, Beijing’s pledge to cut steel production to curb carbon emissions is not looking too good.

With Chinese steel makers currently making enormous margins off their production, Beijing achieving a cut in overall steel production without more serious intervention currently seems rather unlikely.

RELATED: Next battleground with China

This is where things get even stranger.

According to a report from Bloomberg, the Chinese government is likely to reduce the number of special local government bonds in order to reduce various budget deficits. These special local government bonds are mostly used for steel heavy infrastructure spending.

A survey of economists concluded that the total issuance of these special bonds would drop by around 7.9 per cent in 2021, the first drop in overall issuance in at least six years.

As the debt burden of local government in China continues to bite, we have arguably already seen a result of this belt tightening.

Beijing has ordered a halt to work on two major high speed rail projects worth 130 billion Yuan (around $25 billion Australian dollars) as a result of rising concerns about debt levels.

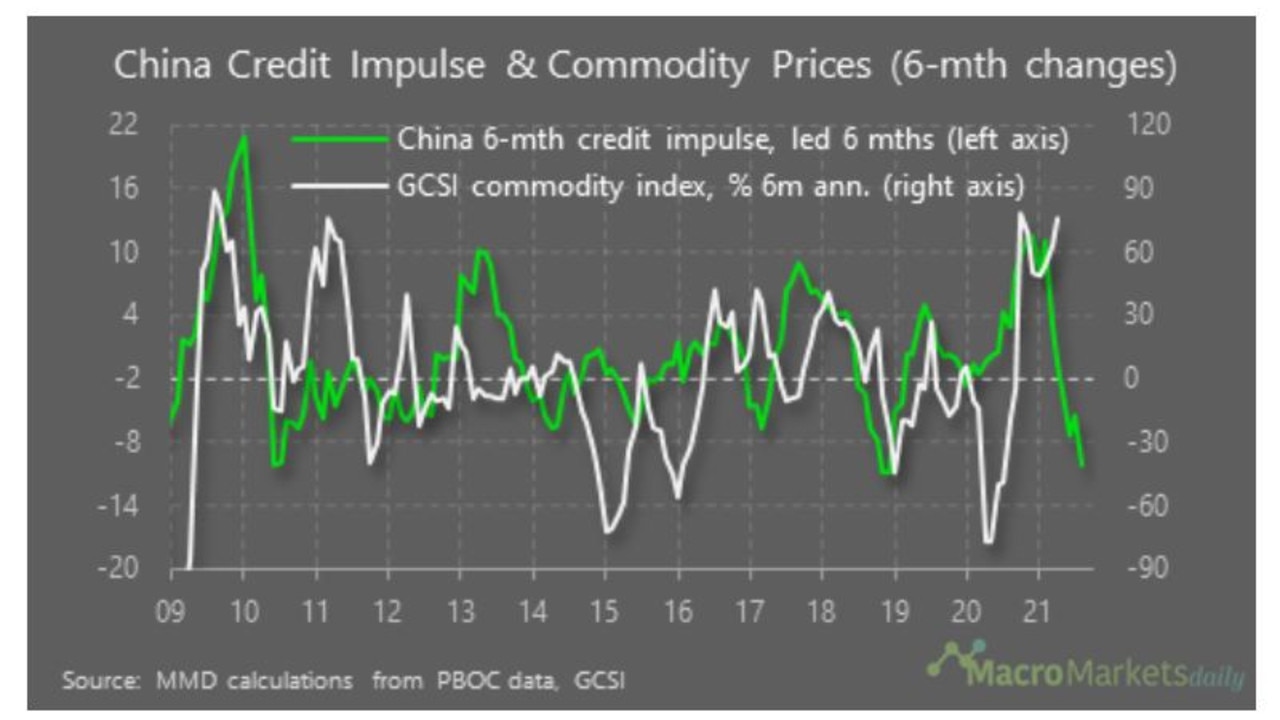

This reduction in the growth rate of China’s debt load has already shown up as a significant contraction in China’s credit impulse, which has historically been linked with commodity prices.

RELATED: Copper, iron ore prices hit record high

But what we have seen so far is the polar opposite, commodity prices continuing to soar higher and demand for steel remaining strong.

As a result of this strong demand, as of May 1, Beijing has implemented taxes on steel exports and cut tariffs on importing raw steel materials.

China’s secret stockpiles of steel

Despite accusations of China “dumping” steel in multiple markets around the globe in recent years, now all of a sudden Beijing seemingly can’t get enough of steel and other commodities.

In September last year, Bloomberg reported that Beijing was planning on building a vast strategic reserve of commodities, after witnessing the impact of the coronavirus crisis and deteriorating diplomatic relations with the US and its allies.

In the drafting of the plan for these secretive stockpiles, which may be the world’s largest, Beijing seeks to build a plentiful enough stockpile to withstand supply disruptions and any possible eventuation.

With purchases of commodities and the size of reserves held by the National Food and Strategic Reserves Administration all secret, if Beijing were stockpiling vast quantities of steel and commodities, we wouldn’t necessarily be aware of it.

Given Beijing is prioritising greater levels of self-reliance in its latest five year plan, amid rising tensions with the United States and major commodity producers like Australia, it would not be surprising to see Beijing taking this opportunity to add to its vast stockpiles.

Should Australia stockpile minerals?

As geopolitical tensions continue to escalate between not only Beijing and Washington, but around the world, the International Energy Agency (IEA) has recommended Western governments start stockpiling critical minerals.

In particular the IEA focused on minerals essential to a green energy transition such as lithium and cobalt.

With China also producing around 60 per cent of the world’s rare earth minerals, there are concerns that rising great power tensions could interrupt the supply of these key raw materials.

These rare earth elements are instrumental raw materials in the production of everything from smart phones to advanced guidance systems for missiles.

Despite the Chinese government’s repeated pledges that steel production would be reduced in order to meet emissions targets, it currently appears unlikely to happen unless Beijing slams the brakes on later in the year.

For the time being at least, the reasons for record levels of steel demand within China remain unclear.

It is possible Beijing could be stockpiling commodities as part of its recent five year plan emphasising self-reliance and President Xi’s own desire to prepare for an unexpected global shock.

After all, if the West is increasingly looking to stockpile commodities amid rising tensions, it makes sense Beijing may be charting a similar course.

Given the opaque nature of the Chinese government and the limited information we do have, an educated guess may be the best we can do.

But as the aggression in the tone of diplomatic communications between the United States and China continues to rise, the possibility that Beijing is stockpiling raw materials for a crisis is certainly something to watch for.

Tarric Brooker is a freelance journalist and social commentator | @AvidCommentator