Australia’s iron ore golden age ‘well and truly over’ as nation falls behind in ‘green steel’ race

Australia’s iron ore golden age is well and truly over. A new age is dawning – but it looks like the country may have already missed the boat.

Australia’s prosperous Iron Age is well and truly over. A new age is dawning – but will it be an economic Stone Age?

The “dig it and ship it” economics of Australia’s iron ore industry has been political cocaine in Canberra’s halls of power for well over two decades.

Tidal surges in export revenue saved national budgets and, therefore, governments.

When those profits ebbed, so did political fortunes.

But just as Colonial Australia’s gold and copper booms came to crunching ends in the late 1800s, the age of iron-driven economics is ending. Fast.

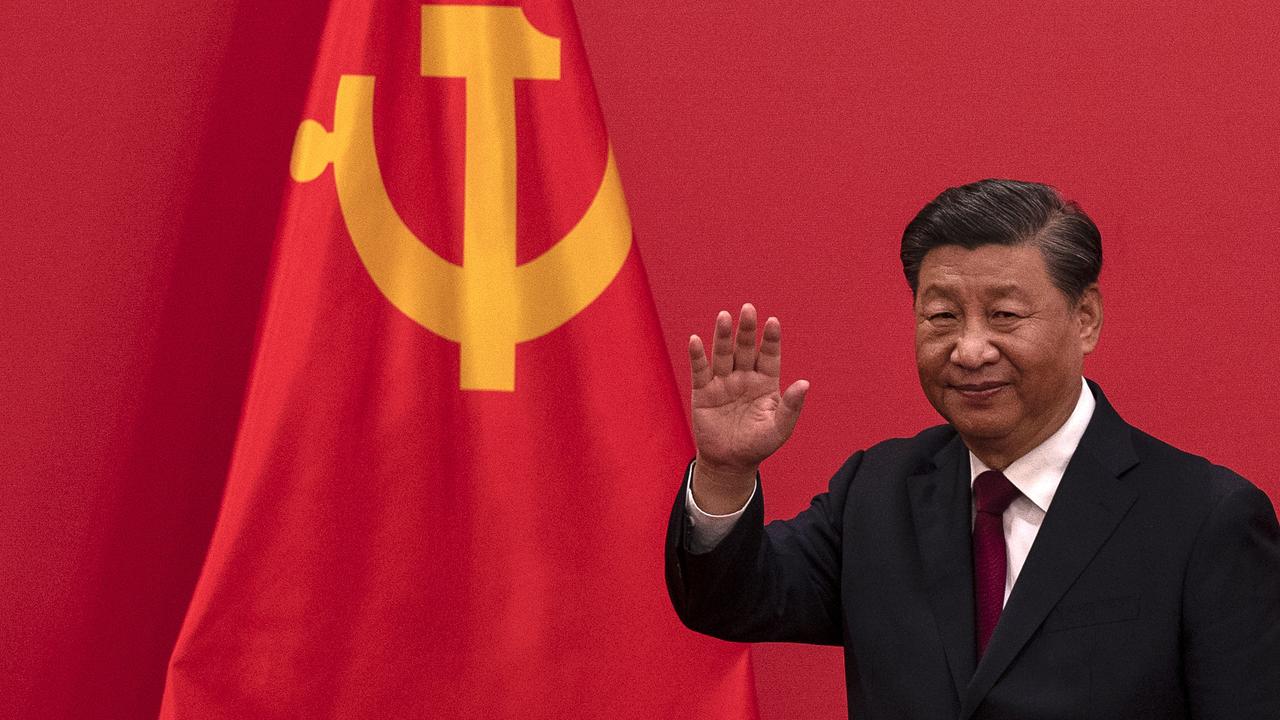

China’s economic woes are an obvious cause.

It imported 84 per cent of Australia’s almost 900 million tonnes of production in 2022.

And iron ore alone accounts for about one-fifth of Canberra’s export revenues ($133 billion in 2022).

But the industry was already staring down an existential crisis.

Digging iron ore. Shipping iron ore. Refining pig iron. Turning pig iron into steel.

It’s one of the world’s most “dirty” processes, responsible for up to 11 per cent of global carbon dioxide emissions.

“The world is undergoing the biggest economic transformation since the Industrial Revolution,” Smart Energy Council advisers Scott Hamilton and Joanna Kay argue.

“A massive global wealth transfer is underway, from fossil fuel-based economies like ours to zero carbon-leading nations.”

It’s no surprise. The need for this change has been argued for some three decades, but some nations heeded the warnings earlier than others.

RMIT University researcher Dr Charlie Huang said China and major African iron ore producers have positioned themselves well to corner the new industry.

But not Australia.

“Africa, a continent with boundless high-quality iron ore, is poised to become one of the world’s biggest producers of low-emissions steel, rivalling China,” he writes in The Conversation.

“Australia, also blessed with energy resources, but with lesser-quality iron ore and a lower population, might find itself a supporting player.”

Rusted economic foundations

“The truth is we sustain a first-world lifestyle with a third-world industrial structure,” Emeritus Professor Roy Green recently told the Asia Society.

Australia has lost about 110,000 manufacturing jobs since 1996, with most of these having been in critical industries, including automotive, machinery, heavy equipment, building products and chemicals.

Manufacturing now represents just six per cent of the national GDP.

And it’s a downward trend showing little sign of turning around soon.

But it is one that has gone largely unnoticed due to the 150,000 employed by the massive support industry built up around the export of iron ore – until now.

“As China transitions away from traditional steelmaking processes and towards scrap metal and direct reduced iron (DRI), the demand for Australia’s high-grade iron ore is expected to diminish,” GlobalData industry analyst Vinneth Bajaj states in a recent report.

“This fundamental shift in the industry could lead to increased price volatility as supply and demand dynamics adjust.”

And Canberra’s budget has little else to fall back on.

Feet of clay, or spine of steel?

“Australia is at a fork in the road,” Hamilton and Kay argue.

“Australia’s economic future and these high-paying jobs depend on our ability to add value to its critical and strategic minerals – and to make products for the future, including green iron.

“Australia’s reliance on iron ore and fossil fuel exports will put our entire economy and quality of life at risk.”

But Dr Huang, also an adjunct professor at the China-based Wuhan University of Science and Technology, warns: “Australia, the world’s biggest iron ore exporter, won’t have the field to itself”.

“As well as the potential sources of power needed to make green hydrogen and steel, Africa is blessed with unusually large quantities of high-quality iron ore,” he said.

And China is already funding a new 600km railway to access Rio Tinto’s new Simandou mine in southern Guinea.

It’s producing some of the world’s most highly concentrated iron ore.

Western Australia’s Pilbara region accounts for about 90 per cent of Australian iron ore. Very little of it is of sufficient quality to feed next-generation electric-arc furnaces.

“(Africa) has the opportunity to use its population, energy resources and high-quality iron ore to dominate steel production during the second half of this century,” Dr Huang said.

Winds of change

“While the short-term volatility persists, the long-term vision involves transforming Australia into a global hub for hydrogen-based steel production, leveraging its abundant renewable energy resources and iron ore reserves. This transition promises economic growth, job creation and reduced emissions but requires significant investments,” GlobalData industry's’s Mr Bajaj wrote.

This week, the Albanese government unveiled a new Green Metals Advisory Panel to help chart the future of the nation’s metal producers.

It insists a new green metals industry could earn Australia’s economy up to $122 billion annually and slash carbon emissions by 250 megatonnes.

And with global advanced manufacturing nations already beginning to impose tariffs on “dirty” materials, the need to do so has become pressing.

This means Australia’s traditional “dig it and ship it” approach is unlikely to be sustainable.

Global steelmakers are already examining the cost advantages of building new technology smelters at sites that offer suitable iron sources alongside ample supplies of green hydrogen and green electricity.

“The reality is that companies in Australia are already stepping up to the challenge,” Hamilton and Kay write.

And Australian universities and the CSIRO have been quietly chipping away at the various technical and scientific challenges for more than a decade.

Economic iron fists

Now, Rio Tinto is poised to invest some $215 million to test new low-carbon iron-making technology.

It’s also collaborating with BHP and BlueScope to develop Australia’s first electric-arc smelting furnace.

A revolutionary green hydrogen project at Whyalla is another project. The goal is for GFG Liberty Steel Australia’s Whyalla steel plant to produce 1.8 million tonnes of “green iron” to feed the new generation of electric-arc steel furnaces as they come online worldwide.

And that may help Australia’s mining industry.

Concentrating iron out of magnetite is far easier than it is from iron ore. And Australia has ample high-grade deposits of this previously largely ignored resource.

However, keeping these processes “green” requires vast quantities of hydrogen gas electrolysed out of seawater and electricity produced from solar and wind.

In May, the Albanese government announced plans for significant tax refund incentives to help this new industry get off the ground at a large enough scale to be effective.

Fortescue says it will take advantage of this scheme to “fast track” its two hydrogen projects in WA.

BHP, however, is placing its bets on carbon capture and storage technology in the hope that it can sustain its existing coal-fired smelters until the new technologies overcome their teething problems.

But these Australian operations are already facing stiff global competition.

“Brazil, the Middle East and Africa are also in prominent positions to win the green iron race. Europe is already ahead in building the world’s first green steel plants,” the Smart Energy Council analysts write.

Sweden, for example, began delivering green steel to Volvo at an experimental scale in 2021. It expects to ramp up to a full commercial scale by 2026.

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel