Magazine accurately predicted the future 95 years ago

THESE illustrations were “seemingly farfetched” back then, but fast-forward a century and they have been vindicated.

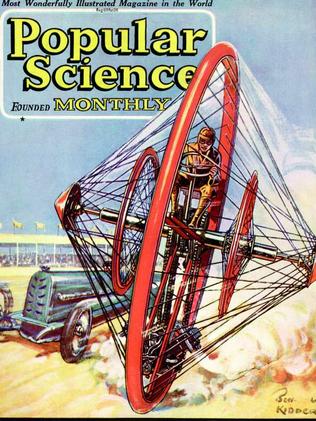

IN APRIL 1923, Popular Science magazine predicted that we would one day be driving gyroscopic motorcycles — sitting high inside a massive wheel — that could reach speeds of 400mph (640kmh).

“You look back on that and you’re like, OK, maybe that was a little bit absurd when it came out. It’s still absurd now,” Popular Science’s deputy editor Corinne Iozzio told the New York Post. “But then you think about where we are with current technology, and you think about Segways and self-balancing motorcycles, and you see that the core principle of the idea hasn’t disappeared.”

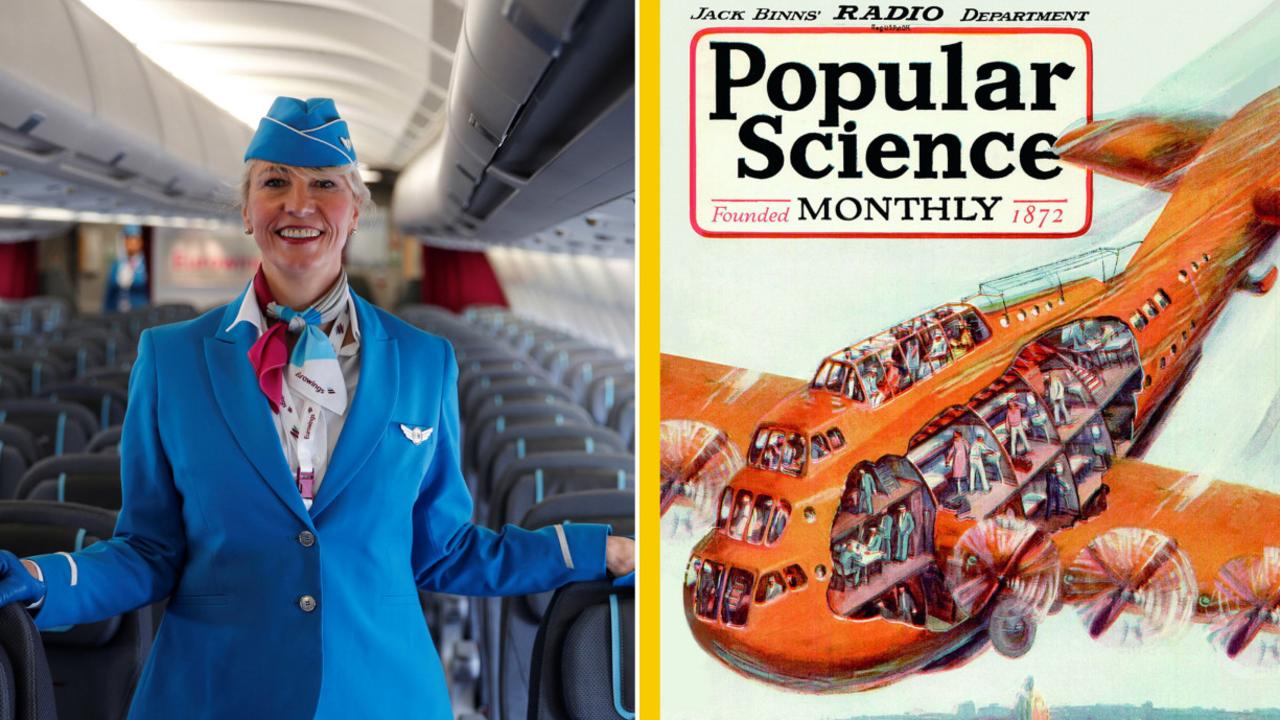

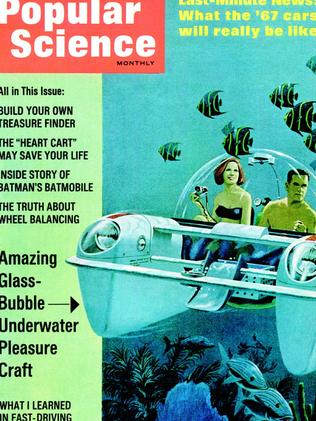

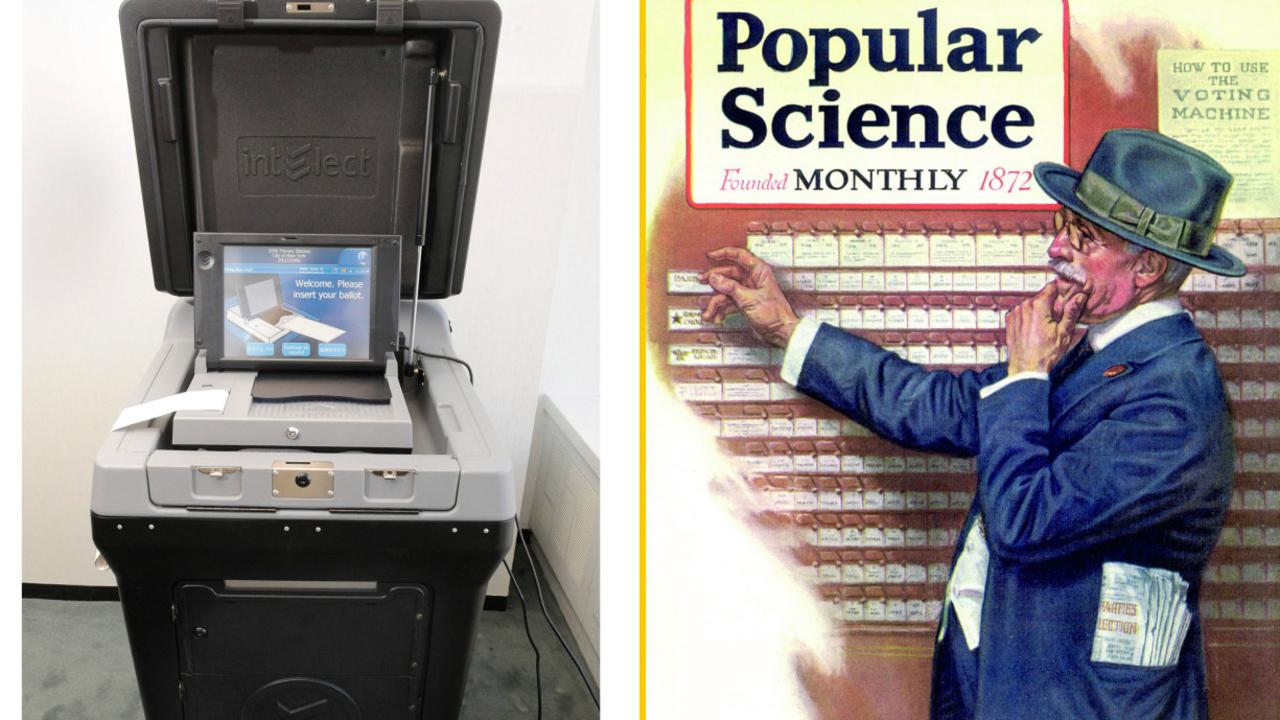

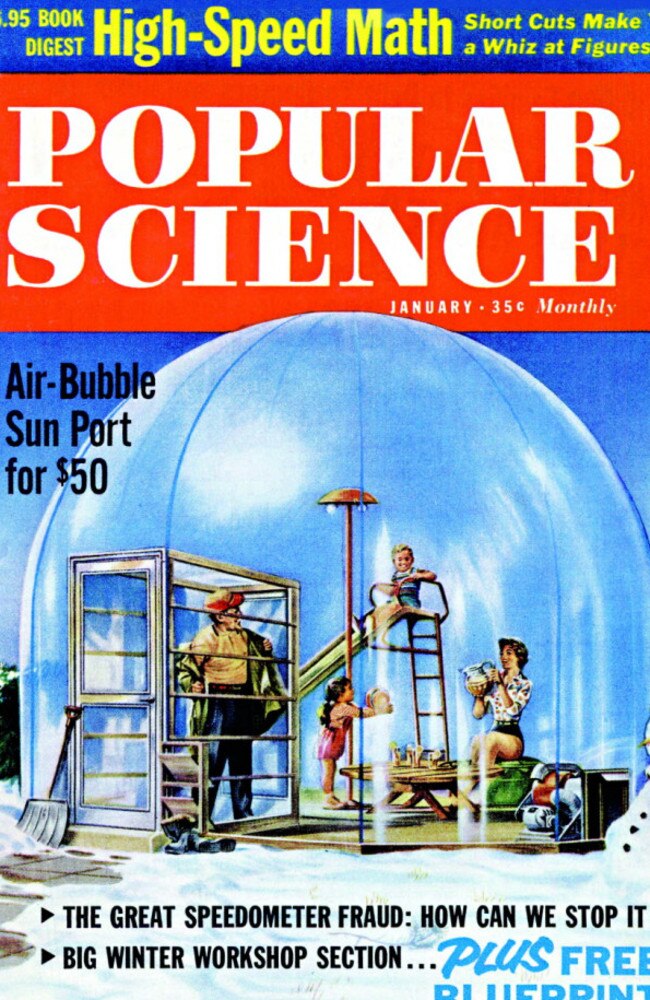

Over the last century, Popular Science has regularly featured illustrations of seemingly farfetched inventions on its covers as a means of foretelling the future.

Some, like the 1921 prediction of a camera that can measure you for a new suit, came true. (Today, you can “try on” clothes in a virtual fitting room.)

Others, like the 1986 illustration of commercial “space planes” that would zip outside the atmosphere and back have yet to be developed.

A hundred year’s worth of these inventions are featured in the new book The Future Then: Fascinating Art And Predictions From 145 Years of Popular Science — out Tuesday, July 10.

Founded in 1872, Popular Science launched at a time when, Iozzio says, “technology and science were starting to bleed into everyday life a little bit more.”

Forty-five years later, “the colour covers are where we really started to get a window into these fantastical visions of what life is and what life could be if we take science and make it popular,” she says.

Amazingly, more predictions than not came true: a 1922 illustration of a multideck passenger jet basically foresaw the Airbus A380, while the December 1970 cover imagines watches that could “keep track of moon phases, show the tides and make calculations”.

Today’s “watches have only gotten smarter since,” the book states.

Mobile phones were featured on the cover as early as 1973, and Popular Science imagined an early prototype of a video game way back in 1938.

But even the publication’s misses show a smart sense of analysing the times we live in and figuring out what comes next.

For example, while the 1931 prediction of “ski wings,” which would give skiers the ability to fly off mountains, was never widely adopted, it presaged the 1997 invention of wingsuits, so beloved by BASE-jumping adrenaline junkies today.

“It’s definitely an oops, but it’s a self-effacing oops,” Iozzio says of the magazine’s more misguided predictions. “What we always come back to is the core ambition of the thing that was on the cover.”

While some covers were depictions of early-stage inventions at the time, others were conceived from scratch.

“We don’t really have a formula,” Iozzio says, “but we think about the motivation of the thing. Is this craft or rocket [or whatever] seeking to solve a big problem, or to push through a barrier? What is the driving force behind it? We always reward motivation and ambition.”

This method often leads to spot-on futurecasting. While the first satellite was launched into space in 1957, Popular Science predicted it in 1949, posing the question, “Is US building a ‘New Moon?’”

At the time, satellites were still in the concept phase, advocated by scientists, and science fiction writers like Arthur C. Clarke. But there was no guarantee of their becoming real when the magazine featured them on the cover.

Now a quarterly magazine, Popular Science is still attempting to predict the future with recent covers exploring genetic engineering and human immortality.

Iozzio says the magazine’s current futurecasts largely focus on advances related to artificial intelligence, which she calls a “common thread” in forward-looking advancements today.

“Whether or not people realise it, artificial intelligence is something we’re already interacting with on a daily basis,” she says.

“There’s an artificial intelligence in Google Maps, and now that things like Amazon’s Alexa and the Google Assistant are becoming more prevalent, we’re starting to have voice-to-voice interaction with artificial intelligence. With things like self-driving cars, the way we’re going to come to trust the interconnectivity and intelligence of our devices is going to continue to inform everything we see going forward.”

The magazine’s editors hope readers will see their predictions not just as indications of a possible future, but as a springboard for conversation.

“I want readers to absorb these as a source of inspiration,” Iozzio says, “as a way to say that we’re always thinking forward. We’re thinking creatively and scientifically about the problems we’re facing and about ways we can address those problems from a practical standpoint and in a sci-fi future — how to think way outside the box. Very often, what ends up happening through the course of history is that we land somewhere in the middle.”

— All captions excerpted from “The Future Then: Fascinating Art And Predictions From 145 Years Of Popular Science”.

This originally appeared on the New York Post and is reproduced with permission.