Dell officially goes private: Inside the nastiest tech buy out ever

HAVING bought back his company for $26 billion, Dell founder Michael Dell is free to say and do what he wants. But he has no plan to abandon PCs.

Eight months is a long time to stay mum, especially for a tech industry wunderkind, as Michael Dell was, and one of the world's richest men, as Michael Dell is, while enduring daily bombs from Carl Icahn about his leadership and ethics.

("All would be swell at Dell if Michael and the board bid farewell," Icahn tweeted at one point.)

So as he strides in front of 350 employees in the glass-enclosed conference room of Dell's Silicon Valley division a few weeks ago, with celebratory gourmet cupcakes frosted with the company's blue logo nearby, you can literally feel a weight coming off his chest. "It's great to be here and to not have to introduce Carl Icahn to you," says Dell, the parry prompting laughter and cheers. "We're the largest company in terms of revenue to go from public to private. In another week or two we'll be the world's largest startup."

It's not that Dell hasn't been talking. Ever since February, when he announced his plan to take his eponymous company private, armed with his own fortune and billions from the private equity firm Silver Lake Partners, he's traveled the globe–including three trips to China–privately reassuring everyone who would listen that Dell was business as usual. But at the advice of counsel he kept a tight lid on talking about the buyout.

Now, having closed a $25 billion deal to take the company he founded in his dorm room private, the shackles are off. He can say what he wants–and do what he wants, too. After mixing in his 16% ownership, valued at more than $3 billion, and another $750 million in cash, with $19.4 billion from Silver Lake and a consortium of lenders, he now controls a 75% stake in the Round Rock, Tex. company. The only investor conversation he has to have, he says, is with "self."

So what is Dell now saying to himself, as well as customers, partners and employees?

Most critically, the world's third-largest personal computer maker has no plans to abandon the PC, despite that product line's sinking fortunes. In fact, he plans to sell way more of them and, if the recent past is any guide, he may just sell them at a loss. Selling commodity boxes on the cheap allows him to get Dell in the door to upsell customers on lucrative software and services. Dell has driven down the prices of PCs many times before. But a PC maker selling PCs as a loss leader? That's the kind of thing you get to do when you take a company private. "We've always viewed [PCs] as a business that's got a life cycle to it. Growth is in new areas, and it's a business you've got to manage very efficiently from a cost structure. It's still a great way to get into new customers," says Dell.

The world got a taste of this land grab in Dell's last quarter as a public company. Net income dropped 72% from a year earlier–but Dell's PC share ticked up one percentage point, its largest move in almost three years. There's a long way to go to rebalance the business. After four years of work and $13 billion in services, software and other acquisitions, the firm still gets more than 60% of revenue from PCs. Dell's market share in services and software stands at less than 1%, but these are the only categories making money and growing. Enterprise solutions, software and services revenue was up 9% in the latest quarter, and services comprised 100% of total operating profit. And in addition to battling traditional rivals like Hewlett-Packard and IBM, the company also has to worry about IT newcomers such as Amazon and Rackspace, which are wooing businesses with cloud-based services.

Yet some of the smartest minds on Wall Street, including Icahn, are convinced Michael Dell and Silver Lake got a steal at $25 billion, putting 20% down. "I agreed with the shareholders that he was not paying a fair price for Dell and that they were getting hosed," Icahn says.

Hosed may be too a strong a word. No one else but Dell wanted the company that badly, not even Icahn, who had a "win win," walking away from eight months of grandstanding with a stake worth $2.2 billion, and after squeezing out another $500 million for shareholders. The growth-challenged company will be buried under just less than $20 billion in debt in an industry in secular decline.

But Icahn knows what Dell does: that without dividends and buybacks, he should have enough cash flow to cover the interest payments. And without the public markets to worry about he has the flexibility to pull off the rebalancing act. Silver Lake, which in its last three tech deals reportedly made 213% on Skype, 730% on disk drive maker Seagate Technology and 430% on chipmaker Avago Technologies, can do the math, as well. Conservative estimates peg the potential returns on this leveraged buyout at 11% a year, based on the most recent dismal earnings. And if cash flow growth comes back–or the current results are being, shall we say, sandbagged a bit? Then Dell will neatly bookend the founding legend of his University of Texas dorm room.

"Michael has extremely exciting software assets that haven't been valued by Wall Street because they're surrounded by the legacy PC business," says Salesforce.com CEO Marc Benioff. "For Michael to realize the value of these new assets–he has this incredible security asset as well–Michael needs to take Dell private and restructure the company."

Before diving into the challenges ahead, though, there's a question a lot of people have pondered that needs asking: Why him? Dell had more than five years to lead a turnaround and failed. Shareholders have been treated to a negative 43% total return since he reclaimed the CEO job. Why not just walk away with his $16 billion in net worth ($12 billion of which is outside of Dell) and establish a new legacy?

"I will care about the company after I'm dead," says Dell. "I love this stuff. It's fun for me. I couldn't be more thrilled to have control over my own destiny in a way that is not possible as a public company."

Brilliance and Bravado

Before Mark Zuckerberg and Kevin Systrom, Drew Houston and David Karp, Michael Dell defined the myth of the American tech prodigy. Only Bill Gates and the Apple founders could come close. Dell was 23 years old at his IPO in 1988, five years younger than Zuckerberg at the same milestone. He was 29 when his company hit $1 billion in revenue and 31 when it hit $5 billion.

The company's first president, Lee Walker, remembers the first time Dell came to see him in 1986. "He eats most of my sandwich and all of my soup, and in between slurps asks me if I can be president of his company. … He had no money, no access to money." Yet Walker eventually came on because he could see that Dell possessed both brilliance and the bravado to think he could take on HP and IBM as a college freshman simply because he was willing to assemble PCs himself and sell them directly over the phone.

By 2001, Dell overtook Compaq for the worldwide PC lead and retook that lead two years later from a now combined HP-Compaq. The company soon expanded into servers, storage, printers, mobile phones and MP3 players. Things were going well and Michael Dell was ready to let go. In 2004 he kept only the chairman role, handpicking former Bain consultant Kevin Rollins as CEO.

But underneath things were starting to slip: customer service, product quality, strategy, vision. By 2006 Dell had lost its No. 1 spot in the market, having failed to see the massive industry shift from desktops to notebook PCs. In 2007 Dell was back in the boss' chair, ready to rethink the PC business and where the information technology industry was headed. Selling only PCs wasn't going to cut it. Dell needed to expand its software, networking, security and services offerings. "At the scale of Dell, the only way you were going to move the needle quicker was acquisitions," he now says.

So Dell went on a $13 billion buying spree, consuming more than 20 firms. The biggest: the 2009 takeover of IT services provider Perot Systems for $3.9 billion, purchased at a 68% premium.

It wasn't enough. Dell was slow to the shifting IT tides. Other tech giants, including HP, IBM, Cisco and Oracle, were already diversifying to grab market share from one another's businesses. In consumer, Dell was the opposite of the Apple machine: no mobile, no retail, few premium products that stood out. "We were all a bit frustrated with the pace at which this transformation was moving," says Brian Gladden, Dell's chief financial officer since 2008. "It's a work in progress."

Worse, investors weren't giving the company credit for progress made, with headlines focused on shrinking PC sales and market share, rather than on the fact that it had built the non-PC business from $10 billion to a "pretty impressive" $21 billion in five years. "We're working hard to build this $21 billion business to $30 billion, $40 billion–and basically you've got public investors saying, ‘You're a PC company, don't invest in all this stuff. Don't acquire all this stuff. Don't go invest in R&D,'" Dell says. By last June shares, which had traded above $40 in 2005, had sunk below $12.

‘I Would Take Dell Private'

The chain reaction of the past year started with a conversation in June 2012. Dell's second-biggest shareholder, Southeastern Asset Management, was underwater and saw little upside. But it would be willing to roll a chunk of its 146 million shares into a management-owned entity if the takeout price was right. Dell says that he'd thought about going private before but never broached it with the board. Still, his interest was now piqued. In July Dell was at a tech conference in Aspen and in the hallway ran into Silver Lake partner Egon Durban. "He said, ‘Hey, I'd like to meet with you,'" says Dell. They agreed to meet up in August in Hawaii, where both own luxury homes on the Kona Coast.

They went for a walk, and Durban, who had an investment team take a deep dive into Dell before the meeting, floated the same idea. "I told Michael, ‘If I were in your position, I would try to take Dell private. And I don't think you need Silver Lake to do it,'" Durban recalls. As to why the deal made sense, he adds, "If Dell today were simply a PC company with the ambition of transforming itself into a full-blown enterprise solutions provider, that prospect would feel pretty scary. What in fact has happened, however, is an incredible thing. Michael has already transformed Dell into a thriving enterprise company."

Dell also knows a thing or two about private equity. His MSD Capital, with $12 billion in assets, is bigger than Silver Lake's most recent megafund. Dell reached out to another Hawaii neighbor, George Roberts of investment firm Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, to get his thoughts. Roberts agreed it was possible and wanted to talk about doing it together.

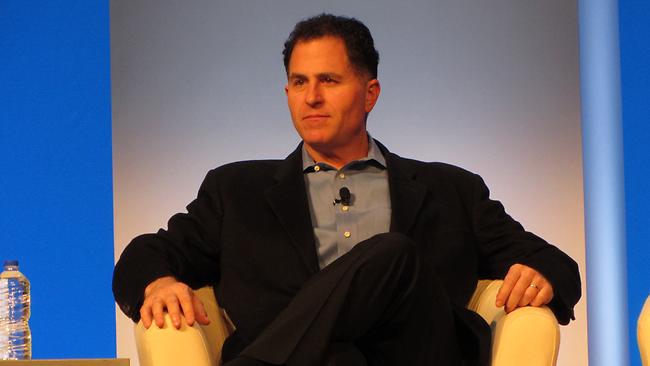

Michael Dell now owns a 75 percent stake in the company. The only investor he has to answer to, he jokes, is "self." (Photo credit: Christopher Peacock)

"So then I said, ‘Time out. Gotta call the lawyer. Don't want to make any mistakes. Tell the board. Do everything the right way,'" says Dell.

Soon after, he notified Alex Mandl, the board's lead independent director, that he was considering buying the company, little knowing then that it would take more than a year (and more than a little anguish) to pull off.

The board, according to the detailed timeline of events recounted in Securities and Exchange Commission filings, formed a special committee to consider the idea and other options. These included separating the PC and enterprise businesses, doing a "spin merger" with the PC unit and a strategic partner, tackling more "transformative" acquisitions, changing out management, doing a leveraged recapitalization, increasing buybacks and dividends, and selling out to a strategic buyer. Mandl gave Dell the go-ahead to call Silver Lake and KKR and tell them the board was open to considering a go-private transaction.Code words started flying: The PC maker was nicknamed "Osprey." Michael Dell went by "Mr. Denali."

Lawyers and advisors weighed in while the special committee sussed out the challenges to Dell's business. There were many. They included the "significant" weakness in the PC market (PC shipments are expected to drop 8.4% this year), share losses in key emerging markets that had been big profit drivers and spotty growth in the enterprise unit. At the same time, Dell saw soaring demand for tablets, which it sells only in limited supplies, and smartphones, which Dell doesn't manufacture at all. Dell was also seeing lower returns on its acquisitions than management had anticipated.

By October Silver Lake (code name Salamander) and KKR had submitted bids hovering around $12 per share. For his part, Michael Dell pledged he would participate with "whatever sponsor was willing to pay the highest price." The November earnings report was dismal–the seventh quarter in a row of results below management forecasts–and shares dipped below $9.

KKR, concerned about PC demand, dropped out when the board's Dec. 4 deadline rolled around, leaving only Silver Lake. On Dec. 6 CFO Gladden provided updates on the business and projections through fiscal 2016. He told the board that "fully implementing" the plan to shift from PCs to enterprise solutions would take another three to five years. It would also take more money, a big concern since there were questions about whether the cash flow from the dwindling PC business would be enough to finance the enterprise expansion. The board asked private equity firm Texas Pacific Group to bid, but it declined two days before Christmas.

By February, with press reports already hinting at the buyout and the special committee convinced there wouldn't be other bidders, Dell and Silver Lake got the go-ahead. In addition to Dell's investment, Silver Lake put up $1.4 billion, banks including Bank of America, Barclays, Credit Suisse and RBC provided about $16 billion in financing, and Microsoft tossed in a $2 billion loan to one of its biggest partners. Dell Inc. says the cost to service its debt will be less than what it spent on dividends and stock buybacks over the last five years.

The proposal also included a provision for a 45-day "go-shop" process in which other parties were invited to come courting. Enter Icahn. The veteran opportunist says he got interested after some big Dell shareholders (he won't say who) called him for help. In a Mar. 5 letter to Dell's board he let them know he now owned $1 billion in shares and thought the Dell-Silver Lake bid was too low. Blackstone also sniffed around during the go-shop but withdrew in April, also citing the PC market slump.

Icahn's $10 Million Man

Throughout the go-private saga, Dell never lost a big customer. That doesn't mean those customers weren't nervous. A few asked for a change-of-control provision in new contracts if Dell were no longer CEO. Others took "a bit of a wait and see [stance], especially when it got a little bit more turbulent," says Marius Haas, who headed HP's networking business and joined Dell in 2012 to run Enterprise Solutions. When the going got rough, the company sent in its CEO to reassure them that it was business as usual. "Michael equals Dell, Dell equals Michael," Haas says. "He is the culture for employees, customers and partners."

By June it was just Dell and Icahn, who spent nearly $1 billion more to buy out Southeastern's shares. The billionaire investor used tweets, open letters–headlining one "Let the Desperate Dell Debacle Die"–and media interviews to barrage shareholders with his message that the buyout undervalued the company, and that Michael Dell should be fired and the board replaced. He pushed for a leveraged recapitalization, pressing the company to borrow billions for a stock buyback to buy out investors at a premium and issue warrants for the purchase of additional shares in the future if the turnaround played out. To help with his case, Icahn and Southeastern say they recruited a big-name tech executive (whom FORBES believes to be former Compaq CEO Michael Capellas) as a potential replacement for Dell and flew him out to Icahn's house in New York's Hamptons. "He came for lunch and stayed until midnight," says Icahn. "We were so serious about getting him that we agreed to pay him a fee of $10 million just to sign on to our team, whether we won or lost." The candidate soon after got cold feet. "I'm not casting aspersions, but something happened to change his mind."

By the time September rolled around, it was pretty clear that Icahn wasn't a serious threat to derail the deal. Most of the bidding up by Silver Lake and Dell took place in the early going, and Dell says that Icahn never submitted a formal offer after his June proposal.

"It's a big poker game to him," says Dell. "It's not about the customers. It's not about the people. It's not about changing the world. He doesn't give a crap about any of that. He didn't know whether we made nuclear power plants or French fries. He didn't care."

He points to Icahn's stance that shareholders should have sought appraisal rights–a process by which a judge determines the value of the shares. "He goes on national television and says appraisal rights is a ‘no-brainer,'" Dell says, shaking his head. "If you ask any lawyer who knows anything about appraisal rights, they will say this is not a no-brainer. This is very complicated. This is years of difficulty." After shareholders voted with Dell, Icahn said he decided against seeking appraisal rights. "He just lies," says Dell.

Donald Carty, the longest-tenured member of the board besides Dell, says the going-private transaction was handled "by the book" to make sure shareholders' interests were the priority. Business schools will study it one day as "a classic case of doing it right," he predicts.

Southeastern didn't make out so well, despite kicking off the whole affair. It began buying Dell shares as early as 2005 and will likely take a $500 million loss from the transaction.

"This was not done to get a bump up in the shares. We felt that company was worth over $20 and the shareholders were not being served by the board," says G. Staley Cates, president of Southeastern. "The best alternative all along was a leveraged recap, because you start with $15 billion of cash on the balance sheet."

The New Dell

Dell has no shortage of people who think that the founder, in this case, can be the same person who is the disruptor. "You have someone who knows the business well and is not dewy-eyed with a romanticized view of the past," says Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, a professor at the Yale School of Management, who has known Dell for two decades.

"I'm thinking of the guts he has to do it," adds Aneel Bhusri, co-CEO of software maker Workday, which counts Michael Dell among its early investors. "He could have walked off into the sunset and said ‘I can move on.' I think he's making the harder choice." Adds Silver Lake's Durban: "We would not want anyone else other than Michael to run Dell."

The "new" Dell starts with some promising metrics. The company that made its name selling direct has more than 140,000 channel partners today, with about $16 billion of Dell's nearly $60 billion in annual revenue coming that way, up from zero in 2008. It also doubled the number of sales specialists with technical training to 7,000 in the past four years. Two out of three business customers' first experience with Dell is buying a PC, and about 90% of those customers go on to buy other products and services. The trick is getting the sales force to cross-sell. How far along are they on that effort? "We're in the second to third inning," says Jeff Clarke, head of the PC business.

It would help to have new technology to sell. Dell has traditionally been stingy on research and development, spending $1 billion a year, only 2% of sales. In absolute dollars HP spends three times as much. Cisco spends five times as much. But new gear is coming: One brisk seller is the PowerEdge VRTX, introduced in June, that combined servers, storage, networking and management technology into a single chassis designed for small businesses.

The value in technology is moving from the PC to the cloud. Dell just snagged a big executive from Indian services giant Wipro to run its 10,000-employee cloud infrastructure group. A typical customer of the new Dell looks like Barclays, which uses Dell's "private cloud" to run its mobile banking services.

One of the bigger unnoticed changes is the switch in the "superstructure" of Dell from one organized around customers (consumer, small business, public and large enterprise) to one built around the four operating units (PCs, services, software and servers and storage), supported by one sales organization. As a private company unshackled by Wall Street's 90-day attention span, Dell has boiled the priorities down to just two metrics: cash flow and growth. "It's incredibly clarifying," he says.

There are two ways to boost cash flow, of course, and one of them is to slash costs. Two years ago Dell Inc. vowed to take out $2 billion over three years, half of it from the PC business. As a private company it could do far more. Dell may need to move away from the build-to-stock model–customers call up and say what they want and Dell builds it, without keeping costly inventory on hand–to a build-to-inventory approach, where the company builds models and sells them off the shelf. It's a cheaper approach and has made Lenovo the world's largest PC maker, with increasing margins.

In some ways trying to squeeze billions out through thriftiness brings Michael Dell back to his roots, when the company was famous for charging employees for their coffee (as it still does). The cupcakes that he was celebrating with in Santa Clara are a tradition that dates to when Dell had its first $1 million sales day. On that day everyone got a cupcake. But, notes Dell, "just one."