Change.org and the business of outrage

IF YOU thought Change.org was a feel-good charity, you’d be wrong. The company is making big bucks off your anger.

THERE’S no doubt Change.org has made a difference in a lot of people’s lives.

From national headline-grabbing campaigns to grassroots, local causes, the online platform has already hosted hundreds, if not thousands, of petitions in Australia. More than 2 million Australians have inked their names to a Change.org petition since the site launched here in 2011.

On the surface, Change.org has the trappings of a social movement — empowering everyday people to band together and demand change for the better. That’s ranged from national boycotts of radio hosts who have offended the populace to securing life-saving surgery for one person. Its largest local petition received almost a million digital signatures.

Change.org’s website bills itself as “the world’s platform for change”. That’s a mission statement anyone can get behind. And the name itself — Change.org — conjures up the kind of fuzzy, inspirational feelings that leaves you full of hope for the future — as intangible as that is.

But Change.org isn’t just a platform for progressive change, despite what its .org designation implies. It’s actually a clever business model that’s reaping decent money from the “outrage economy”. As a private company, Change.org is under no obligation to disclose its earnings, but Change.org’s global head of external affairs, Jake Brewer, told news.com.au the firm has not yet turned a profit.

For most people, a .org, as opposed to a .com (short for commercial), at the end of a website URL implies a not-for-profit organisation. While it may have started out that way in 1985, along the way, the .org has become an umbrella designation for all kinds of organisations, including commercial entities.

On the “About” section of its website, Change.org outlines its mission statement and how it’s funded. While it refers to itself as a “company” and a “business”, it doesn’t explicitly spell out that it’s a for-profit business. Instead, it’s couched in terms which focus on its goals of people empowerment and social good. The company addresses the .org designation in these terms: “This focus on mission instead of profit is why our name ends with .org instead of .com”.

For Change.org, its commercial operations are largely focused on advertising. However, it’s not traditional web advertising: serving you an ad on its website promoting a hotel, some shoes or a random shop. Instead, Change.org makes its money through “sponsored petitions”.

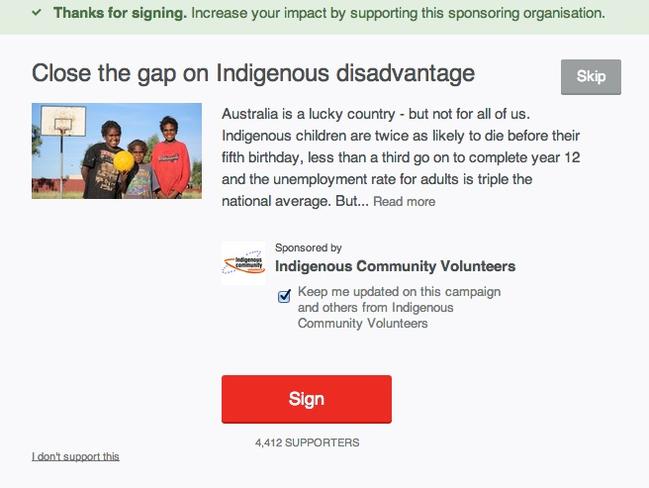

This is done in two ways. The first is petitions that are sponsored by an organisation or company which pays Change.org to host it and spread the message to its members. According to national director Karen Skinner, Change.org has 25 clients in Australia. Its clients locally are overwhelmingly not-for-profits such as Amnesty International and Walk Free, while it has one commercial company on its books.

These clients don’t just pay to get their petitions in front of people interested in their agenda. For them, the ideal outcome is if, when signing their petition, you also leave the box ticked that gives the client your email address. Change.org gets paid for every email address that is sent to their clients.

It’s a great way for organisations to grow their membership database. It can also be a great way for Change.org users to hear from organisations that work in a space they’re interested in. Assuming, that is, those users were cognisant enough to realise they’d agreed to have their details forwarded on (it’s an opt-out system, rather than opt-in).

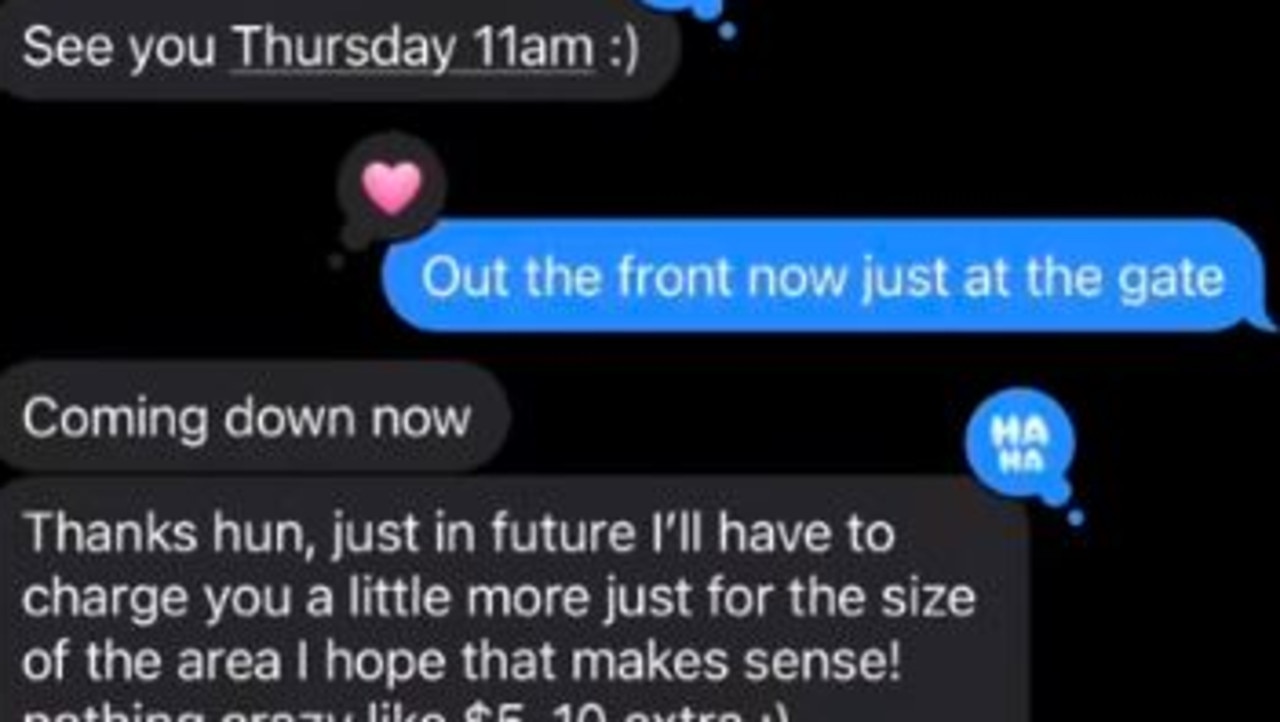

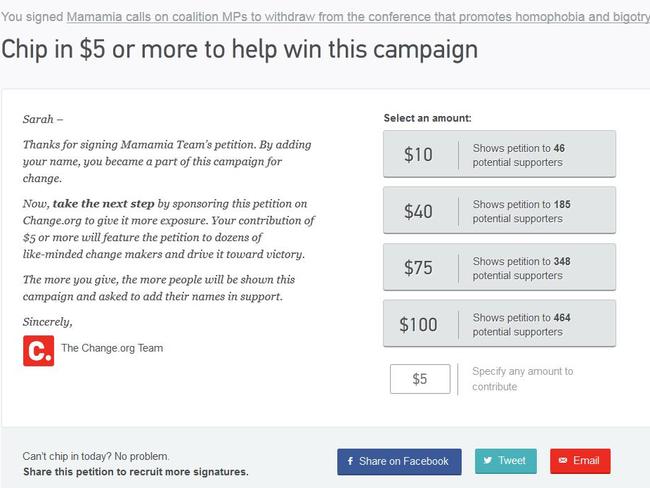

Last year, Change.org rolled out another product to increase its revenue. Everyday users can now sponsor existing petitions on the website by putting their own money behind a cause they care about. For example, if you’re on the site and you sign a petition someone else created, you can throw your own money in to pay Change.org to put that petition in front of more people logging on to the site.

Mr Brewer also said the company is trialling a third revenue plank in the US in which Change.org clients send emails to Change.org members who have not previously signed a petition from that client — nor have they agreed to give their email address to that client.

When asked if people would be comfortable with receiving emails from an organisation they have not specifically engaged with, Mr Brewer said the product was not available to everyone and that it was still in a testing stage to determine user suitability.

“We like to be proactive and get a sense of what our users want,” he said. “Our values have to be how we drive revenue and the reason we drive revenue is to drive more change in the world.”

Change.org has clients in the commercial space but Mr Brewer points out that non-profits don’t have a monopoly on doing good. But, he said, the company does ensure campaigns aren’t just a play to sell products.

Change.org is part of a newish wave of companies that claim to place “social good” at the core of their mission. Known as social enterprises, and sometimes as B Corporations, these businesses try to combine social good with profit. Think Tom Shoes, which gives a free pair of shoes to a disadvantaged child for every pair purchased by a consumer. The idea is, you can do good and make money.

But as a business model, it’s still evolving. Mr Brewer said every dollar Change.org made was plugged back into the business so it can expand, giving more people access to its platform. But Change.org still has investors who, presumably, would like to see a return on their investment someday.

“Eventually we want to make a profit and give back to our investors, essentially in the form of a dividend,” he said. “We’ve committed to never go public or sell out, which are the primary ways investors exit. But we have values-aligned investors and they’re committed. It’s not a short-term exit strategy for them and it’s about finding a revenue-positive business model than can work. It’s evolving; I would be lying if I told you we found the perfect answer.

“The non-profit model is great for a lot of things but it’s not great for a global technology company that’s available to anyone in the world. We want give people a democratic tool.”