Beef and Wellmania: The new front in telling different stories

Beef is a fantastic show for many reasons, but the one that’s surprisingly secondary is how it’s telling a different story.

In some ways, it didn’t take long to get from Crazy Rich Asians to Beef, but in other ways, it’s taken so long to get here.

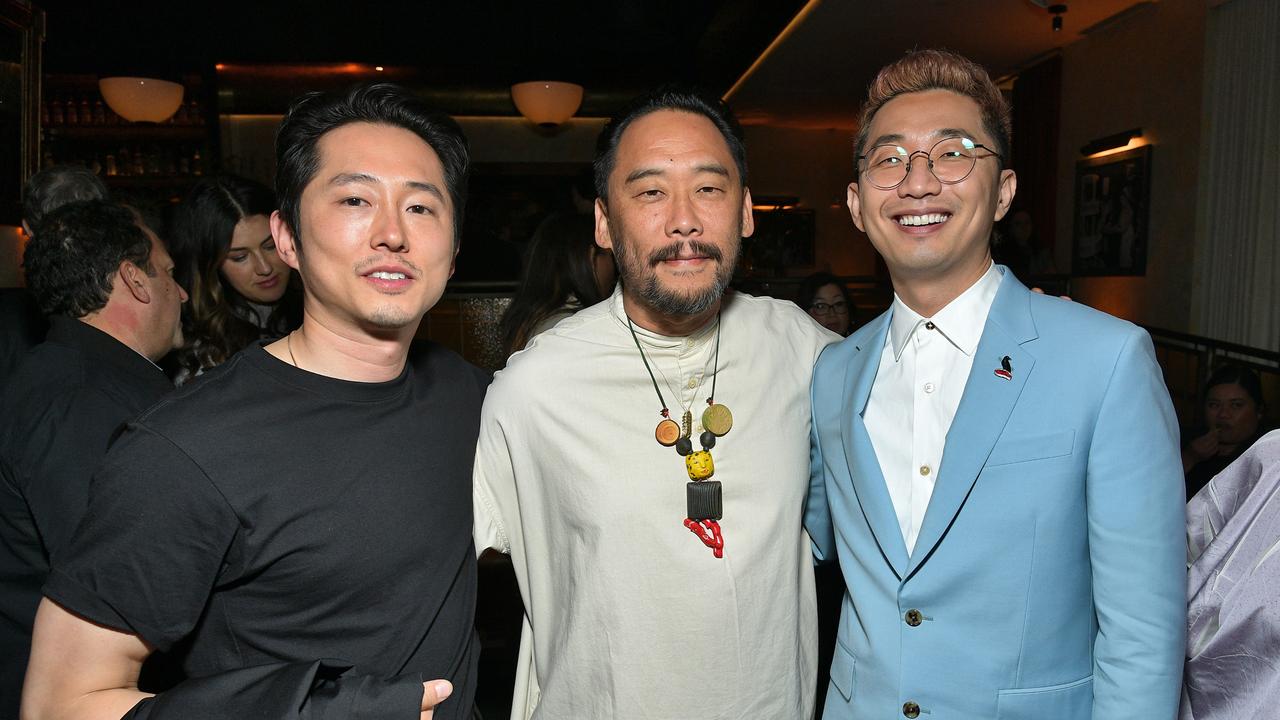

Beef, the acclaimed Netflix series starring Ali Wong and Steven Yeun, has been attracting the kind of critical buzz rarely seen for any new series. It’s punchy, dark and hilarious, with a dash of existential dread thrown in for good measure.

The series is about two strangers who destroy each other’s and their own lives in an escalating feud after a road rage incident. And it’s already in the awards conversation – no surprise, because from the writing and directing to the performance and even the soundtrack, Beef is in rhythm with its ambition.

And despite having two leads who are Asian-American, a creator who is Asian-American and a supporting cast dominated by Asian-American actors, the representation aspect of Beef is secondary in the show.

That’s because in the five years since Crazy Rich Asians broke ground in Hollywood as the first all-Asian cast for a mainstream Western film in a quarter of a century, representation has evolved. It’s a massive moment, partly because it’s kind of stealthy. If you weren’t looking for it, you might’ve even missed it.

The characters in Beef are Asian-American, but they are also Los Angelenos, they’re wealthy and they’re struggling, they’re arseholes and they’re clueless, they’re smart and they’re dumb. And they have this insane thing happen to them that has nothing to do with their cultural background.

The story of Beef could’ve happened to anyone, no matter their heritage, but the characters are grounded in the specificity of their cultural backgrounds. They’re not colourless, or colourblind, which often defaults as white.

That’s the difference. These are second-generation immigrant characters but it’s not screaming “immigrant story” because not every aspect of every diaspora community’s day-to-day happens because of their culture, but their backgrounds might influence how they react to certain things, or it might have a role in how they got to where they are.

Take, for example, Yeun’s character, Danny. Danny makes a lot of bad choices in his life due to a range of factors that form who he is, but his primary motivation is his filial duty to his parents. He’s driven by this need to provide for his mum and dad after they lose their motel in an incident for which he feels responsible.

Danny’s burden could be applied to other immigrant backgrounds, but it has the specific weight of a second-generation Korean-American experience. Add to that the character’s involvement with a Korean-American church.

Those parts of Danny are not the reason the story of Beef exists, but they add richness to its world.

So too do Beef’s supporting cast, which is made up primarily of Asian-American characters, including many who are not related to the leads. Often in a Western movie or TV series, on the rare occasion that there is more than one character from a marginalised cultural background, they’re family.

Beef is not alone in this movement. Australian Netflix series Wellmania has three Asian-Australian characters in its main ensemble, portrayed by J.J. Fong, Remy Hii and Alexander Hodge. None of them are related.

Fong plays Amy, the best friend to Celeste Barber’s lead character Liv while Hii’s character Dalbert is her pending brother-in-law, and Hodge plays Liv’s love interest, Isaac.

Set in Sydney, where Australians with Asian heritage make up more than 20 per cent of the population, it makes sense that Liv’s circle would have more than just one token Asian.

Fong told news.com.au, “Amy was a rounded character and I really like that they didn’t make it about her being Chinese. I liked that she was a really feisty, ambitious and successful career woman and a mother and partner and all the other stuff.

“Which is what I want to play. I never want it to be about my race, which has always been the case in the past. I feel like more and more, that’s the case, and the roles I go for, it’s not always about that.”

While Amy’s story isn’t tied to her Chinese background, she is still coded as Asian-Australian beyond her appearance – there are scenes in the family home with her parents speaking Chinese. These are the details that layer a character.

Fong cited Wellmania co-creator Benjamin Law’s involvement. “I was really grateful to be able to play, and to have Benjamin Law in my corner as well, which was great. I think that Amy is the character Benjamin based on himself, and that he took care of, and he wrote.”

Law, a writer and broadcaster, has worked on some of Australia’s few screen projects with significant Asian-Australian representation, including The Family Law, a three-season comedy based on the experiences of his childhood growing up as the only Asians in a Queensland town.

Australian stories such as The Family Law, New Gold Mountain (which Law also worked on), and Hungry Ghosts are about the immigrant experience, and these shows as well as American films such as Lulu Wang’s The Farewell, Lee Isaac Chung’s Minari and Crazy Rich Asians have told beautiful, moving and resonant tales that were invisible for so long.

These stories of belonging are deeply empathetic and help people connect with and understand those with different histories.

But they’re not the only stories out there – and they’re not the only experiences the Asian diaspora community have.

Fong also stars in Creamerie, a Kiwi black comedy set in a post-apocalyptic scenario in which all the men have died from a pandemic, leaving women to run the place. She is one of three leads in the show and all three characters are Asian-New Zealander.

Again, the story isn’t about them being from an Asian background, the story is about three women trying to contend with the trauma and farce of living in a dystopian world. And they happen to be of Asian backgrounds.

Hii, who has also starred in Spider-Man: Far From Home, Aftertaste and Harrow, told news.com.au said he has been intent on playing characters that have a reason to be there outside of their ethnicity but for all the strides the industry has made, it still has work to do.

“We’re still struggling with it in this industry, in Australia. When the auditions come my way, a lot of the times, there’s not the authenticity or depth there. And it comes back to having someone like Benjamin on the project.

“Diversity does not begin and end in front of the camera with the actors. Diversity has to be embraced and celebrated at every level, and for our industry, that means people behind the camera in the writers rooms, as producers, as executive producers. What’s the balance in cultural backgrounds, socio-economic levels, gender and everything?

“I’ve seen so many scripts in the past year or two in this country that are just box ticking, and that is something I think we really need to look at, because it’s not authentic storytelling and it doesn’t make a good story.”

Hii said in Australia, he is still mostly auditioning for guest or supporting roles, but in the US, they’re often for leads. “That’s the part where I go, ‘Australia, we can do better than this’.”

Hii’s contention that who is telling the story matters as much as the actors on screen carries a lot of truth.

Beef’s creator Lee Sung Jin has a credit list that includes tonally ambitious comedies such as Silicon Valley and Tuca and Bertie, but he is also someone who grew up attending a Korean-American church.

So, when he wrote the scenes with Danny in church, it comes from being a talented TV creator and from lived cultural experience.

When Ali Wong and Randall Park co-wrote the screenplay for rom-com Always Be My Maybe, they did so as artists who had the authority to create and play those characters.

It’s great that Beef and Wellmania are part of the next front of diversity on screen, but the work isn’t done, and it doesn’t end here, but at least it’s evolving.