George Mladenov shares inside story of his brutal Survivor injury

In this exclusive book extract, Survivor star ‘King George’ reveals what happened when he suffered a brutal injury during filming.

The January 2023 premiere of Australian Survivor: Heroes vs Villains started disastrously, when the very first challenge of the season sent two contestants to hospital.

Both fearing they’d be eliminated from the game - and more importantly, facing potentially life-threatening injuries - contestants George Mladenov and Jackie Glazier made an agonising trip to a Samoan hospital to await their fate.

In this exclusive extract from his new book, How To Win Friends and Manipulate People: A Guidebook for Getting Your Way, Mladenov tells the inside story about what happened after he copped one of the most brutal injuries in Australian Survivor history...

Despite returning for my second season of Survivor as a stronger, more confident player, I suffered a pretty horrendous injury at the first hurdle that almost ended my game right then and there.

After working so hard to be physically fit for my return to the game, it wasn’t my quads that nearly let me down – it was my head.

Day Two in the game, all still hyper on excitement and adrenaline, we were summoned to our first immunity challenge. It was an obstacle course with a very tricky start.

Players had to hurl themselves, in pairs, onto one of two big boxes, which would then spin and fling them off the other side into a pit of mud.

This was my moment: the first physical challenge to show off to everyone – players and viewers alike – that this wasn’t the soft-boiled George of the previous season. I wanted them to see what $545 a week of kangaroo patties and deadlifts looked like. That I had changed. That I was strong. That I would destroy people with my mind and my body.

So when it was my turn, I sprinted as fast as I could at the box, throwing myself onto it with velocity. My body landed on it with a thud as my tribemates spun it so that I’d be catapulted off the other side. It was all going so fast: the running, the spinning, the yelling. Before I knew it, I landed headfirst, at speed, into the mud pit underneath the box.

I saw stars. Thick, muddy water coated my face. My recollection was that I dragged myself to the edge of the mud pool, at which point I could feel my neck was in pain. Jonathan could see it had been a bad fall, so he screamed the single word you never want to hear on Survivor: ‘MEDIC!’

Hearing that word in reference to yourself is every Survivor player’s worst nightmare. It could literally be the end of your game. My neck was throbbing, I couldn’t see, and before I knew it I was in a neck-brace and a Samoan ambulance being taken for an urgent assessment. If you need to leave the game to receive medical attention, your window as a Survivor player starts to rapidly close. First, a stopwatch is started: you can only have 24 hours out of the game before you’re disqualified.

And that’s if you are even allowed back in: they can’t send a sick or injured player back into the game, and oftentimes people never come back from the tent.

I can only recall a few things from that accident. Firstly, I asked to be taken off the stretcher to finish the challenge (which production, of course, refused). When the senior members of the crew voiced their concerns, I then started to worry that my neck was broken. And I remember tearing up as I was being accompanied by a doctor on the 90-minute drive to the main hospital in Apia, Samoa.

It was only when the ambulance eventually arrived at the hospital that I realised there was someone laid out next to me in the emergency department: Jackie Glazer, a fellow returning player and professional poker player. I had met Jackie 10 years earlier at a poker game - playing with her in Samoa felt like finding an ace up my sleeve. But now the odds felt impossibly stacked against us.

‘George, it’s me,’ she rasped. Her voice was so close, but I couldn’t turn to look at her because I was immobilised in the neck brace.

It turns out that Jackie and I were injured at the same time during the challenge. I hadn’t realised she was also in trouble – I couldn’t see after falling head first into that mud pit, and then I was laid out on the ground, put in a neck brace and told not to move. All the while I was wondering if I had a spinal cord injury, I assumed she’d already sprinted off to the next obstacle.

But here she was with me, the two of us having bounced off to hospital on the backroads of Samoa, every pothole sending shivers of pain through our aching bodies.

Despite the little resources that Samoan nurses work with, I felt like I was in a safe pair of hands in the Apia hospital.

Jackie and I were given fentanyl – a definite first for me – while we waited for our X-rays. I remember it making me feel happy and giddy despite the circumstances. As the night ticked along, Jackie and I kept ourselves distracted by telling each other stories about getting into the game. It helped take our minds off things (and I’m sure the hardcore painkillers didn’t hurt, either).

At one point, we could hear a conversation between the Samoan doctor and the doctor from production. They said: ‘The male patient has to be admitted. I suspect he has fractured his neck. The female patient can’t be admitted as we don’t have the expertise to treat her in Samoa. She has to be sent home.’

Jackie and I immediately started crying. They believed I had broken my neck. My thoughts about returning to the game moved to fretting about what the recovery process was for a fractured vertebrae.

Jackie’s injury was so severe that she had to be sent to a bigger hospital. It sounded like we were both out of the game. It was one of the lowest points of my life. Jackie was wheeled off, and I was left in the hospital room alone. I was told that I would need to have an MRI scan to confirm the fracture. In Australia, sometimes it can take weeks to book in an MRI scan. But in Samoa, there is one qualified radiologist and one MRI machine. Even more unluckily, most people do not work in Samoa on a Sunday, and it was late on Sunday night heading into the wee hours of Monday morning.

What kept my spirits up at the time was the fact that the Survivor production team looked after me to the best of their abilities with the resources available. I even was given the local spiritual treatment: in the middle of the night, as the hours were ticking by on my 24-hour deadline, the local Samoan fixer was by my bedside literally praying for me. She kept telling me that the doctors in the hospital were her nieces and nephews, and that I would have my MRI scan.

At about 3am, the one radiologist on the island came to my bedside and told me I was being taken to the MRI room. After the prayers, this felt like a miracle. What I didn’t know then was that the Samoan Health Minister had received a call from the fixer and demanded that the radiologist front up to the hospital to do my scan.

I remember my emotions during the MRI so clearly: I was torn between being worried about my ability to walk back into my camp, and my ability to walk properly again at all.

I obviously didn’t want my neck to be broken, but at the same time, I couldn’t stop focusing on the fact that the very narrow window of opportunity to re-enter the game was closing. They had told me if there was no fracture, they could consider sending me back to camp. So when the scan ended, I basically yelled to the radiologist, ‘TELL ME NOW IF IT’S BROKEN.’ His words were to the point: ‘Not that I can see, but there is significant swelling.’

This was music to my ears, which I had become very aware of while immobile in my neck brace. I had another five hours for the scan to be reviewed by doctors in Australia. At around 8am I was given the good news: no break or fracture, just significant swelling. I demanded the neck brace to be taken off and for me to be taken back to camp immediately.

The doctors had other ideas. I was advised to sit upright in my bed for 30 minutes because I had been immobilised horizontally for about 21 hours at that stage. Finally, when I got up on my feet, I still had limited mobility in my neck movements. My right shoulder was not feeling good, but I was able to walk to the bathroom.

It was then that I saw myself in the mirror for the first time and burst into laughter. My forehead was still bloody and muddy and I looked like I had been badly beaten up outside the local bar. But the Samoan fixer’s prayers had seemingly worked, and before I knew it, I was discharged and being driven back to the Villains camp.

But I still wasn’t in the total clear to re-enter the game. I had to have a serious chat with the Executive Producer and the psychologist at their production camp. Clearly it would have been their worst nightmare to have two medical evacuations from the game, on the same day, so early in the season.

The psychologist did an assessment of me. He was worried about my emotional trauma. I was worried about having lost 23 hours in the game to work the numbers.

‘There’s no medical basis to not let me return,’ I said to him bluntly. ‘I am going back in – rain, hail or shine.’

They gave in. I was cleared. I asked for my Buff and backpack, ate an apple that was on the table – my first meal in three days – and told them both that it would look good on camera for me to return bloodied and bruised. I was ready.

I was driven a bit closer to camp and remember walking down the path while telling myself that I was lucky. Lucky my injury was not as bad as Jackie’s, lucky that my dream was still alive, and lucky that all of the energy, time and money I had put into getting my body stronger for the game might have been the difference between being able to return and being flown back to Australia in that neck brace.

When I got back into camp, everybody was happy to have me back except for Michael and Simon, who seemed happy I wasn’t seriously injured, but annoyed that I returned. The tribe couldn’t stop talking about how bloodied, battered and bruised I was. Shonee, Liz, and Stevey insisted on trying to wash me in the sea water; for me this was literally like my baptism back into the game, ahead of my resurrection.

I knew I was in trouble from a strategy perspective. My closest ally Jackie was flying home to learn her fate, and my other close ally Anjali Rao had been voted off. I may not have been able to turn my neckfor a few days, but my feet and mind were fine, and I hit the ground running to re-affirm the support of my tribemates, particularly Liz and Shonee. If I had Liz and Shonee backing me, I would survive the next couple of votes, and I may have lost time in the game to build bonds, but I knew I had it in me to make up lost ground.

The greatest risk in the game for me at that stage was infection thanks to the healing hole in the middle of my forehead. I was being pumped with antibiotics and told to somehow ‘keep it clean’.

I would ask my tribemates everyday how my scar was looking, and they would inspect it and hesitantly say ‘better’. Thank God there were no mirrors, otherwise I probably would’ve spent most of my downtime in the game looking at that thing in the mirror and picking at it.

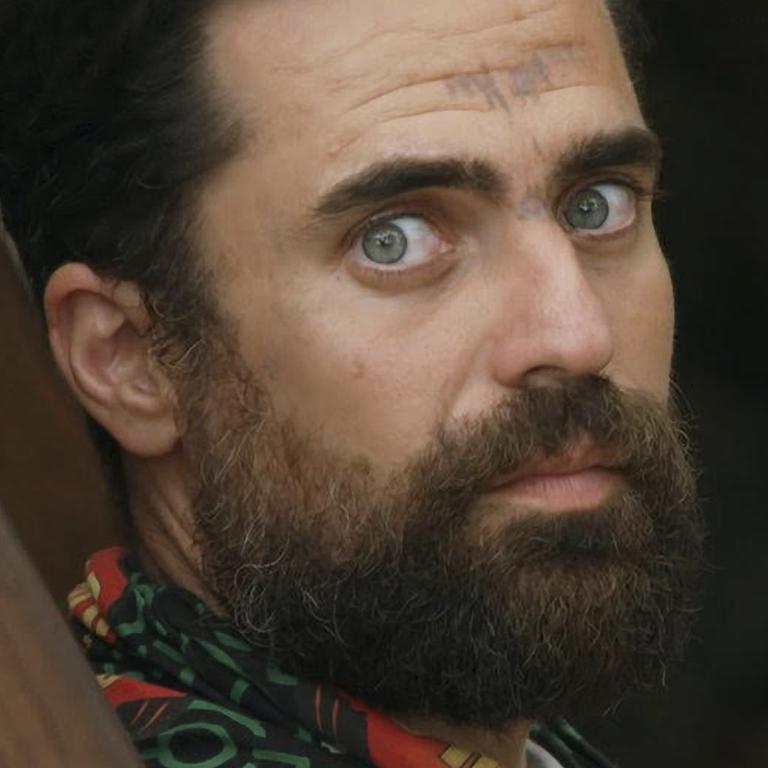

My face scar never went away after the game.

More Coverage

Eventually I visited a cosmetic dermatologist, explained how it happened, and he diagnosed it as a traumatic tattoo – essentially the mud tattooed my forehead during the impact on the ground. It seems I’d hit the mud so hard, ripping my skin in the process, that the mud had imprinted itself into the underlayer of my skin like a tattoo. No amount of sea-water baths would remove it.

The pain from my injuries lingered through the season, but I didn’t let the trauma stick around and rule my game. My faceplant didn’t ruin the rest of my time on Survivor – in fact, it might have benefited me. I wore my mud tattoo like a badge of honour: King George, weak in challenges? Take a look at this!

How To Win Friends and Manipulate People: A Guidebook for Getting Your Way by George Mladenov is released November 29 by Harper Collins.