James Taylor: A Day on the Green, Sirromet Wines, Mt Cotton

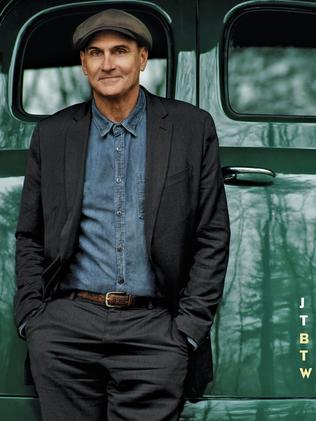

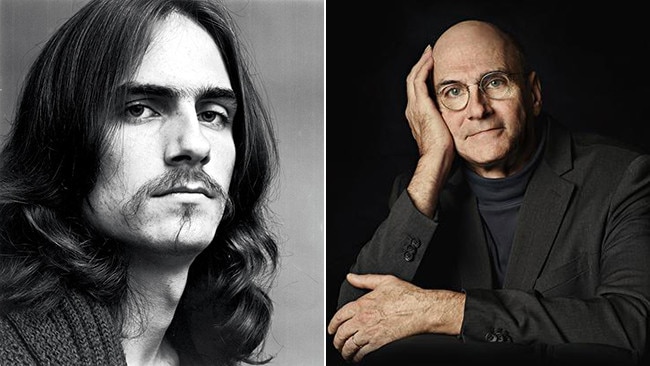

IT’S been almost five decades since the release of his breakthrough album and James Taylor is still in fine voice, and he’s returning for his first tour since 2010.

THERE’S a song on James Taylor’s latest album that is so sunny and familiar – a little bit country, a little bit folk, seemingly effortless, instantly recognisable as Taylor – that it seems to float to you as if on a summer breeze.

Then you listen a few times and see how it goes deeper than it first appears, the way his best songs always do.

Today Today Today is the opening track on Taylor’s 2015 set Before This World, the latest in a solo career that stretches back to his self-titled debut on the Beatles’ Apple label in 1968. It is a song of leaving, starting again, optimistic in tone, but then he sings with the candour that has always been essential to his writing: “Somehow I haven’t died / And I feel the same inside / As when I caught this ride / When I first sold my pride”.

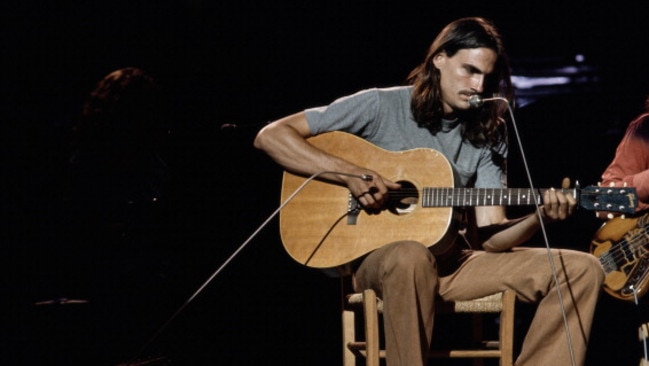

It could easily be a song on his classic 1970 breakthrough album, Sweet Baby James, a record that not only took him to a worldwide audience but led the way for a new breed of singer-songwriters who would flourish in the ’70s with their confessional, personal music.

It’s true, James Taylor so easily could have not made it through, with the doubts and depression that troubled his final years at school followed quickly by a full-blown heroin addiction. This was turmoil at the opposite end of the scale to the inviting warmth of his voice, which by all accounts delighted audiences right from the first moment he started sharing his songs outside of his bedroom.

Part of its charm today is that the voice is completely unchanged by the passing of the years. The loyalty of his fans hasn’t changed either. Before This World, his first album of new original material in 13 years, became his first No. 1 album in the US, a feat not even accomplished by Sweet Baby James. The single from that album, Fire and Rain, remains to this day his signature song and a staple of classic hits radio despite the darkness and despair at its heart. But the rest of Sweet Baby James flowed as sweetly as his finger-picked acoustic guitar. As generations of songwriters who have been inspired by Taylor will attest, the guitar technique is like the voice. It sounds easy, until you attempt to mimic it.

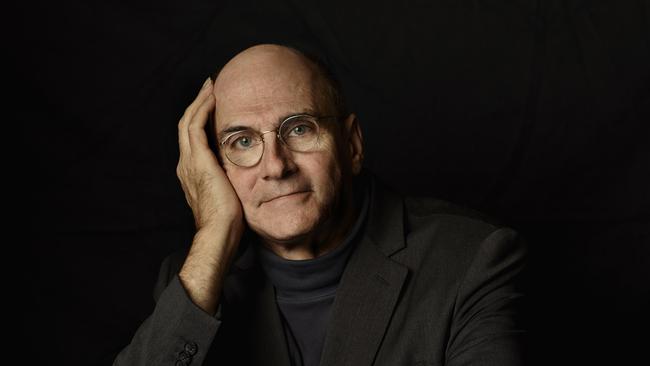

At 68, as Taylor prepares for his first Australian tour since 2010, I ask him if the songwriting muse remains as mysterious as it was to a young man of 20. “I think I do have more of a sense of songwriting as a kind of craft and I see that over time I tend to come back to the same themes that interest me,” he says, his voice as calm and welcoming in conversation as it is behind the microphone.

“When I think back to the beginning as a writer, it was during the folk music surge and the people who came out of it like (Bob) Dylan and Joan Baez. But the main thing about it was that it was accessible; it was something anyone could try. You sort of pretended to be a singer. Or you pretended to be a songwriter and maybe it turned out to be true. That was the way it felt for me.

“In the beginning there was this pressure to express yourself. You never could hold the songs in. Today we seem to live in an age of distraction, with so many things grabbing our attention constantly. When I remember those days it seemed there was a lot of time for me to play guitar, to think about lyrics and songs.

“Growing up in North Carolina, I spent untold hours with the guitar, it never felt like work. It was a very fertile time. So much was being said with the popular music that sprang out of that, FM radio was a new force and it came to together with the post-war baby boom. To be 20 years old in 1968, it was a really exciting time culturally.”

Of those recurring themes in his work, the most prominent has been restlessness and characters who are restless spirits, songs of the road and the sea, of better times ahead. Which is no surprise given the Taylor family bloodlines. On the Taylor side, James is descended from a family of Scottish lairds and seafarers who made their way to America, landing in North Carolina, more than 200 years ago.

The rich and troubled history of the Taylor clan is revealed in Timothy White’s 2001 biography Long Ago and Far Away (Omnibus Press). The book traces the darkness that would recur through the generations with depression, alcoholism and other addictions that would cloud the lives of James’s father, Ike, a doctor and medical administrator and educator, James’s elder brother Alex, who died of an alcohol-related heart attack on James’s birthday, March 12, 1993, and James himself.

When Ike’s mother died from complications in childbirth, his father descended into grief-fuelled alcoholism. Ike was raised by an aunt and uncle and grew into a driven character, receiving high honours at the University of North Carolina before graduating with distinction from Harvard Medical School in 1945.

He married Trudy Woodard, who had studied voice at Boston’s Conservatory of Music. Alex was born in 1947 and James 12 months later, quickly followed by Kate and Livingston in 1949 and 1950, a period in which Ike’s career as a researcher at Harvard was rising. But something in him was drawn back to the family roots in North Carolina, where he accepted a position at the University of North Carolina when the more obvious choice for such a promising career in medicine was Boston.

Part of the restlessness that would imprint in James’s music surely was passed on from the atmosphere at home, growing up in rural isolation on a property outside Chapel Hill, where his father was an assistant professor of medicine and his mother struggled to raise a family now numbering five with the birth of Hugh in 1952.

There was always music in the house – show tunes, light classics; the handsome couple liked to sing, Ike played the harmonica and recorder, James played cello, there was a piano, Kate played dulcimer, and Livingston would improvise: a bass made of a pole and washtub, or cans for drums.

To outward appearances it was a comfortable life. From 1953, the family began taking annual holidays on the Massachusetts island of Martha’s Vineyard. Trudy took the kids, minus Ike, to Europe one summer, and occasionally there were trips to New York to see a Broadway show. On one of these James saw Frank Loesser’s Greenwillow, starring Anthony Perkins. The effect was powerful. He said he wanted a guitar for Christmas.

But it was unsettling at home for the teenage James, with a frequently absent father and an unhappy mother. As he has often said in interviews over more than 45 years, the guitar saved his life. It was his escape and eventual connection to another world.

If that trip to New York to see a musical was a sliding-doors moment in the shaping of a young songwriter, the next was in 1961 on Martha’s Vineyard, where James met 15-year-old Danny “Kootch” Kortchmar, on holidays from New York. James had his guitar and harmonica, Danny a guitar and a knowledge of 12-bar blues. Soon they were playing parties, impressing the girls.

It is Kootch who provides some of the best insights into the young James. In Long Ago and Far Away, he reports: “From the first time we sang together … when I heard his natural sense of phrasing, every syllable beautifully in time, I knew James had that thing. It was really a gift he had. He knew what to sing and when.”

There was a vibrant coffee-house scene on Martha’s Vineyard. Taylor and Kootch won a folk contest at the Unicorn Cafe, while appearing at another club was a duo called the Simon Sisters, Lucy and Carly, the woman James would marry in 1973. But at high school James was not fitting in at a Massachusetts boarding school, where his grades were poor and he was struggling with depression. He confided in a family friend that he was afraid he might take his life and was committed to a mental institution outside Boston for nine months, completing his schooling while there.

Meanwhile, Kootch was burnt out from the gruelling gig regimen with his band the King Bees. When James arrived in New York in 1966 they formed a band called the Flying Machine, but the experience was just as draining as that of the King Bees. Taylor started using heroin: “I just fell into it, since it was as easy to get high in the Village as get a drink.”

Alerted to the danger, his father flew to New York and brought him home, 17, strung out, shattered. But these hard experiences seemed to put a quality into the songs he was writing that most teenagers would never acquire.

“I don’t know who said this, but happiness is not the gift of the gods,” Taylor says now of those formative experiences. “You have to be motivated to want things to change. In some cases it is a matter of taking something that is inside you and trying to get it out of you where you can look at it and deal with it. I do think there was something remedial or therapeutic for me in the music.”

Taylor’s songwriting was maturing fast but he was in no condition to see a way forward with it.

“The Flying Machine had crashed and burned in New York,” he says (the “sweet dreams and flying machines in pieces on the ground” of Fire and Rain). “I had gone back to North Carolina to lick my wounds and get my health back. It was clear I had missed my chance to go to college, and my folks didn’t know what to do with me. After hanging around for a few months I convinced them to buy me a plane ticket to London to visit a friend. I didn’t think of it as a career move but I took my guitar and I had some songs.”

Taylor didn’t see it at the time but the sliding door was open in front of him when he had nowhere else to turn. The experience in London was very different to the one in New York. He met people who liked his music and encouraged him to make a demo tape. The 45 minutes of recording cost him £20, surely the wisest investment of his life.

He had one other tenuous contact. He called Kootch in New York and asked if he still had the number for his friend Peter Asher of Peter and Gordon, the English hitmakers who had toured with the King Bees in the US. He did. Miraculously, the number was still current and Asher picked up. He had just taken the job as A&R manager – the talent scout – for the Beatles’ new label, Apple.

Taylor delivered the acetate from the demo session to Asher, who was so impressed with the songs he played them to Paul McCartney. Taylor became the first non-Brit signed to Apple, a label with a diverse roster including Welshsinger Mary Hopkin (Those Were the Days, produced by McCartney) and English classical composer John Tavener. Soon the young songwriter was recording a debut album at the same studio where the Beatles were working on The White Album. The line “With a holy host of others standing ’round me” on that album’s standout song, Carolina In My Mind, refers to the Beatles, and McCartney played bass on the song. The title of Taylor’s Something in the Way She Moves made at least a subliminal impression on George Harrison, reappearing as the key lyric in one of the most popular songs of all time, Something. For all that, Taylor’s album was a commercial flop, not helped by his return to using drugs and the descent of Apple’s finances into chaos.

After the collapse of Apple, The Beatles honourably didn’t hold him to his contract; Asher became his manager and signed him to the Warner label for Sweet Baby James.

That album showed the broad sweep of music that Taylor had absorbed, from sunny folk to jokey blues (Steamroller Blues) and a version of Oh, Susanna by Stephen Foster, the great American songwriter of the 1800s. This sense of connection to a continuous river of song, from traditional folk to popular composer Hoagy Carmichael and later pop and soul music, became the foundation stone of his work. His studies went even further back than Foster, to a hymn book he discovered while learning the guitar.

“Those Church of England hymns are like Western Music 101,” Taylor says. “They teach you harmonic structure just by singing them. I think of myself as having a very broad base for my music, the music my folks played, Broadway music, folk music, jazz, Celtic music. Then my brother Alex discovered rhythm and blues and turned me on to Ray Charles, Don Covay, the Coasters, Joe Tex, all this amazing stuff. I had a phase where I was listening to a lot of Brazilian music, and after I moved to New York I got a big dose of Afro-Cuban music. All of that filters through my guitar technique, which simplifies it somewhat, but the music starts coming from a lot of different directions.”

While most view the ’70s as the golden age for singer-songwriters like Taylor, it was the obstacles that he found in his way at that time that also created the artist he became and explain why he retains a loyal audience.

“I never thought of records as being a source of income because they never were for me,” he says. “They were making somebody a lot of money but not me. I was always a touring musician, that’s how I make my living.

“You have to be physically fit and in good nick to keep at it. You have to be in the world, really, and it requires high function to do that. I have always thought of the stage as where the music happens, in front of an audience with a community of musicians who are like my family.”

On this tour his band includes master musicians such as drummer Steve Gadd, Cuban percussionist Luis Conte and violinist and harmony singer Andrea Zorn. A radical change of lifestyle – Taylor was so out of control at one point his friend John Belushi said he was worried about him – allowed him to prosper again.

“I did transfer addictions back in the early ’80s. I went from being a substance addict to being an exercise addict; it took me through some very tough times. Sometimes I think the only way to get your body and your nervous system back from a devastating substance addiction is just to burn it off.”

In 2001 he got married for a third time, to Caroline “Kim” Smedvig, who was director of PR for the Boston Symphony Orchestra; they met when Taylor played a concert with the Boston Pops. Their twin sons, Rufus and Henry, were born to a surrogate mother shortly after the wedding. Taylor’s children with his first wife Carly Simon, Sally and Ben, have pursued musical careers, and the twins are drawn to music. Henry sings on Before This World’s Angels of Fenway, about Taylor’s beloved Boston Red Sox baseball team, whose home ground is Boston’s Fenway Park. He was married to Simon for almost 10 years and then married actress Kathryn Walker in 1985. She helped him finally kick his heroin addiction. They had no children and were divorced in 1996.

Taylor says he is in better shape to be a parent this time around, and his own experiences as a teenager have made him cautious. “The twins are 15 now and I pay very close attention to their emotional state,” he says. “I don’t think in Western culture generally we do a very good job of seeing people through adolescence into adulthood. It can be a very hazardous passage.

“Rufus plays the bass and is quite serious about it; Henry plays guitar and sings beautifully. I tell them it would be a rare and unlikely gift to be able to make music for a living. Do music for the love of it, for how it enriches your life and prepare yourself to make your living in some other way. In many ways I think the gifted amateur has the best position of all musicians.”

For James Taylor, though, that was not to be. â–

James Taylor plays A Day on the Green, Sirromet Wines, Mt Cotton, February 11, with supports Bernard Fanning and Kasey Chambers; adayonthegreen.com.au

Originally published as James Taylor: A Day on the Green, Sirromet Wines, Mt Cotton