Australian rock star Daniel Johns’ darkest days

Daniel Johns never wanted to be a rock star. His fame quickly isolated him from his bandmates, causing him to eventually spiral out of control.

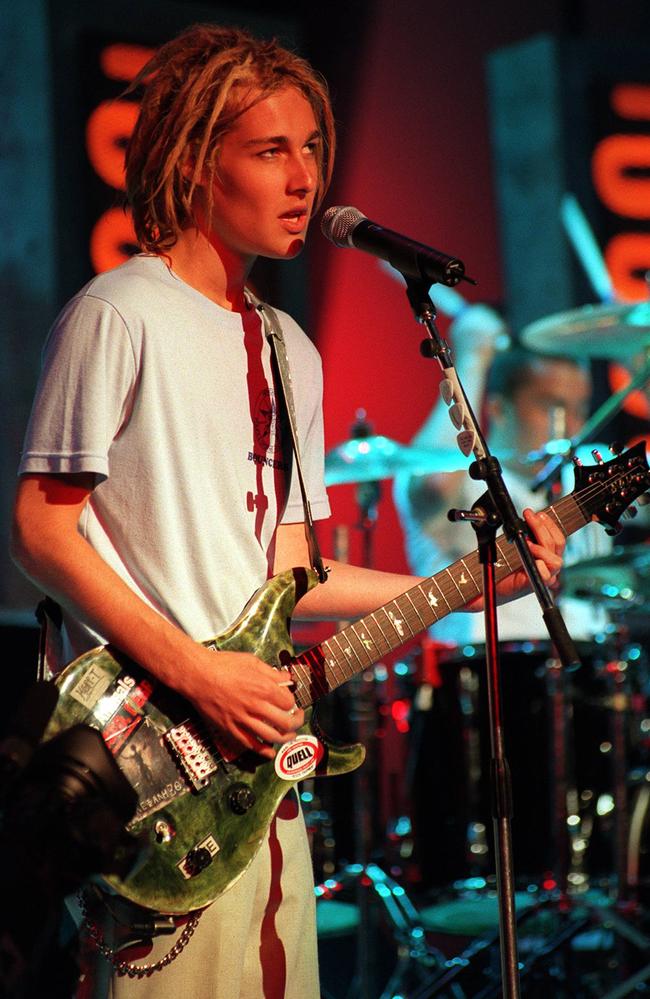

When Daniel Johns was 17, his life spun dangerously out of control.

He was on tour in support of Freak Show, his band Silverchair’s second album. He was one of the most famous people in Australia, and feeling the intense pressure of maintaining his band’s profile in America.

Johns had never wanted to be a rock star; in fact the band’s label and management had taken great pains to ensure the young musicians were granted a steady rise, rejecting coverage in teen magazines such as Dolly and TV Hits and instead positioning them on alternative radio station triple j and in street press.

The plan didn’t work, as their first single Tomorrow went to number 1, sold over a quarter of a million copies in Australia, and became the most-played song on US modern-rock radio.

The band’s debut album, Frogstomp, sold three million copies worldwide, and saw enormous attention and pressure placed on the good-looking frontman, who was only 15 at the time of the album’s release.

Silverchair’s follow-up had “only” sold half a million copies in America, but was an artistic and emotional leap forward.

Moody songs such as Abuse Me and Cemetery hinted at Johns’ despair at the time, while the incendiary Freak and No Association venomously attacked the critics and leeches that traced his every move.

Although Frogstomp contained more than its share of angst, Johns was play-acting, taking inspiration from SBS documentaries, and newspaper articles.

This time around, it was real life he was drawing inspiration from — and things looked bleak.

His fame had quickly isolated him from his peers, and then his bandmates, causing him to become a target of tall-poppy syndrome in his hometown of Newcastle.

“When I was about 16, after school I was getting beaten up, constantly being called fa**ot, people throwing shit into our pool and hassling my family,” he told Juice Magazine in 1999.

“That was really hard. There was a point during Freak Show that Silverchair was about to end because I didn’t want to inflict anything else upon my family.

“I could handle it being directed at me, but when they started doing it to my family it really took a toll that I didn’t think it would. That paparazzi kind of bullshit, photographers following my brother to school and my little sister. I mean, she’s ten.”

Johns had moved out of his parents’ house, and became even more isolated. During the Freak Show tour he had began to get panic attacks.

By the time he had moved, he rarely left the house and had developed an eating disorder — his desperation attempt to regain some semblance of control in his hectic life.

At his low point he reached 50kg, began regularly blacking out and was told by his family doctor that he was going to die.

GOING PUBLIC

In March, 1999, Daniel Johns publicly opened up about his eating disorder for the first time. A day before the first show of Silverchair’s world tour in Brisbane, Johns had decided to confide in a CourierMail scribe.

The result was a front-page story two mornings later, with the headline, Eating Disorder Rocks Teen Star.

The story sent Silverchair manager John Watson into damage control as US promoters flooded his phone with questions about whether the upcoming tour would go ahead.

“It’s disgusting,” he said at the time. “I’m sure there are more important things in the world to put on page one.”

Johns spoke to Rolling Stone journalist Elissa Blake the day before the CourierMail story hit the streets and was again honest about his battles with anorexia.

Johns was honest and able to elucidate his condition, although he had trouble pinpointing the reasons behind it.

“I always knew that I was getting really thin, but I couldn’t really eat,” he told Blake. “It was very confusing; it’s something I look back on and can’t explain what happened.”

He stressed it “wasn’t a reaction to fame or pressure”, although it now seems clear that such intense scrutiny and attention put on a naturally sensitive teenager must have played a central role.

Johns also noted that it wasn’t based on weight issues: “It didn’t start up with me looking in the mirror and thinking I was fat.”

Johns admitted it was when he started blacking out that he truly realised the severity of his condition.

“I realised if I kept going I’d probably die. So that changed my outlook on it. I was forced to go to the doctor and I was told that I was suffering from pretty bad malnutrition.

“Our doctor has known us since we were babies and he was looking really worried. Once I saw that, it just clicked, I thought, ‘This is really f**ked up.’”

Johns admits he was too stubborn at the time to admit anything was wrong, although he was “just eating to be able to move”.

As his obsession with food grew, he became paranoid that people would purposefully poison him.

“We’d go to restaurants on tour and I wouldn’t be able to eat because I was paranoid that there was poison in the food or someone had dropped a pill in the drink or something.”

Speaking about his struggles in 2018, this time with journalist Jeff Apter for the biography The Book Of Daniel: From Silverchair to Dreams, Johns has a more nuanced and adult perspective.

“The only way I can describe it is to say that it felt comforting to be in control of something, like I hadn’t totally lost it,” he explains now.

“The problem is, you think you’re gaining control over something, but in reality, you’re losing control over the functioning of your body.

“Within a few months it got to the point where I was eating just so I wouldn’t collapse.

“At the time, my parents and my brother and sister were the only people I trusted and could see without feeling anxious.

“Of course, they were all worried sick about me, but I couldn’t really see how bad it was.”

Also speaking to Apter, bandmate Ben Gillies describes how their once-tight friendship began to fray, as Johns would want to “sit around all the time and do nothing”.

When forced out of the house by Gillies, Johns was quickly accosted by strangers.

“You care about the guy, but there’s nothing you can do. All you could say was, well I hope he works it out.”

Manager John Watson left Johns alone, but checked in with his family for regular updates, which he described as “pretty intense”.

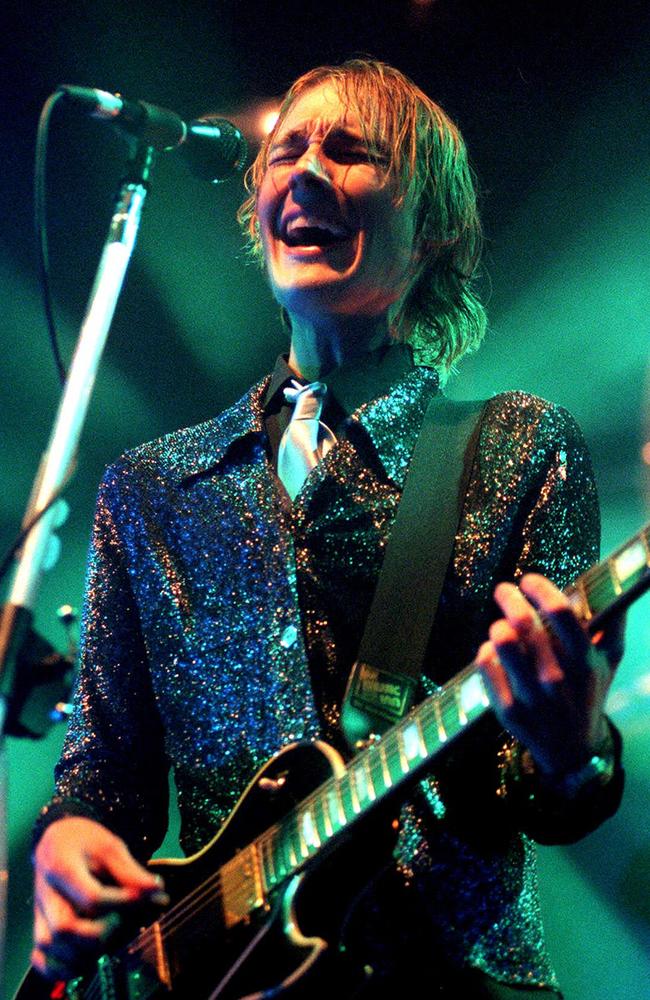

As was the case when he funnelled his anguish into the Freak Show album, Johns again turned to music in order to express and understand his pain. He penned more than 100 poems while holed up in his Merewether house, the words from which became the emotional fulcrum of third album, Neon Ballroom.

Central to this was the raw Ana’s Song, a not-so veiled description of his condition, in which ‘Ana’ was the personified anorexia, recast as a destructive woman who wrestles control from him.

“Please die Ana, for as long as you’re here, we’re not” the song opens, before describing the body dysmorphia that often accompanies anorexia: “In my head the flesh seems thicker.”

It easy to miss the messaging upon a first cursory listen, but the meaning soon becomes clear.

“And you’re my obsession, I love you to the bones,” Johns howls, before declaring that “Ana wrecks your life, like an anorexia life,” decoding the entire anguished analogy.

It was a searingly honest centrepiece to the artistically ambitious Neon Ballroom, an album which arrived in stores less than a week after the CourierMail headline broke the tale of Johns’ health battle.

If that story was dismissed as mere sensationalism, Neon Ballroom and Ana’s Song could not be. It was the final song recorded for the album, brought into the studio by Johns at the eleventh hour.

“It started as a very personal poem”, he explained at the time. “It wasn’t intended to be lyrics to a song, but I ended up really liking the openness of it and liking the fact that I didn’t censor myself.”

His manager and label head both tried to dissuade Johns from including the song on the record, fearing the intense scrutiny it would bring to the fragile frontman might tip him over the edge.

Johns was adamant, and Ana’s Song made the record.

ANOREXIA IS NOT A DEATH WISH

There is much misinformation regarding anorexia, including the oft-reported claim that it is a way of slowly committing suicide.

The reasoning goes, those suffering with the disorder are actively restricting their own diets, and therefore are willingly contributing to their own eventual deaths. This is, of course, a falsehood. Anorexia is a mental issue, brought on by a number of various factors: genetic and environmental.

Johns has stressed numerous times over the year that, although he thought he may die as a result of anorexia, he was never suicidal.

Speaking to Rolling Stone in 1999, he made that clear.

“I never considered suicide an option at all. But when I was really bad with the eating disorder, I thought that I might die and I think everyone that knew me thought I might die if I kept going.”

It also had nothing to do with weight, and everything to do with control, as he reiterated to Apter earlier this year, when being interview for The Book Of Daniel.

“I’m sure the reason some people get eating disorders has to do with a distorted body image, but often it has nothing to do with looking a certain way.

“It’s about gaining control over a part of your life.”

For help or more details about eating disorders, please call The Butterfly Foundation’s National Helpline on 1800 334 673

Nathan Jolly is a Sydney-based writer who specialises in pop culture, music history, true crime and true romance. Follow him on Twitter @nathanjolly