Judy Garland’s wild final years of drugs and cruelty

Before Judy Garland’s untimely demise at just 47 years of age, the star was drug-addicted, an alcoholic, sex-obsessed and suicidal.

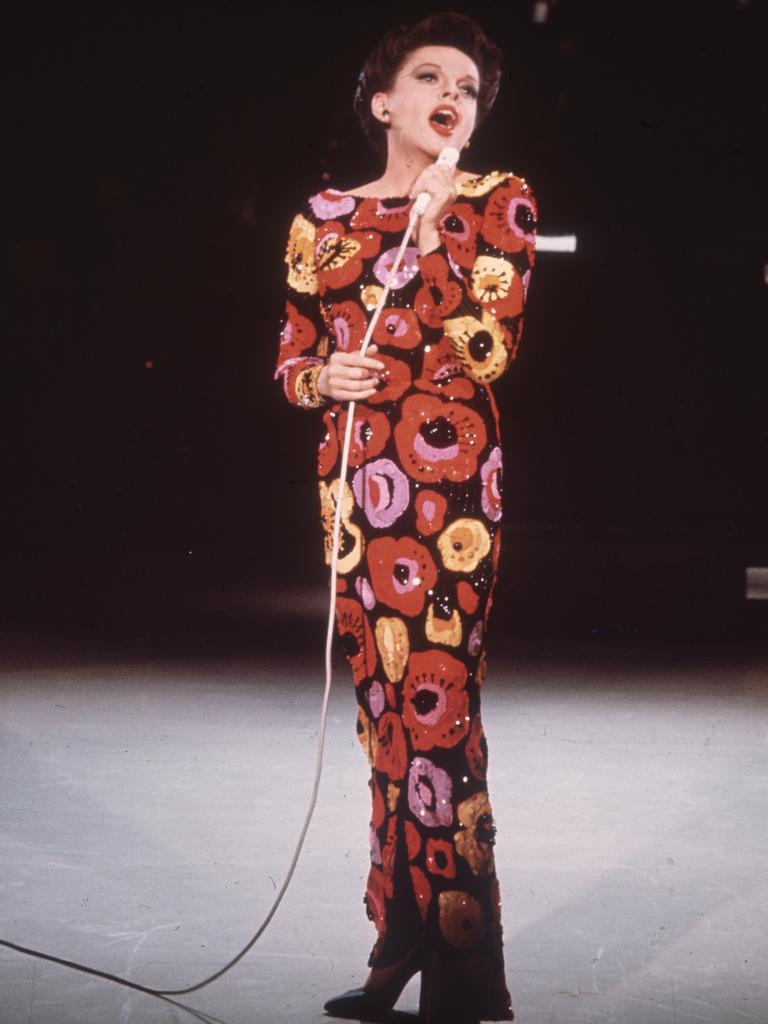

Onstage and on-screen, Judy Garland boasted big, beautiful eyes and one of the most iconic singing voices in Hollywood history.

She was Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz and Esther in A Star Is Born; the singer of The Man That Got Away and Somewhere Over the Rainbow. Behind the scenes, however, Garland was somewhere over the cuckoo’s nest.

The actress, who died from a drug overdose on June 22, 1969, at just 47 years of age, is the subject of a new movie called Judy, which hits Australian theatres on October 10.

The film, starring Renée Zellweger, depicts Garland’s final weeks performing a series of acclaimed concerts in London. But years before her untimely demise, she was already drug-addicted, an alcoholic, sex-obsessed and suicidal.

Stevie Phillips, who began as a secretary at the New York-based Freddie Fields Associates, worked her way up to become Garland’s manager from 1961 to 1964, accompanying the singer on her cross-country concert tours and witnessing all her bizarre behaviour along the way.

There was the Caribbean vacation where a nearly naked Garland serenaded rowdy longshoremen in the Bahamas with Over the Rainbow from her hotel balcony. The time where she broke the mirror on her make-up compact and used the shards to slice up her face. And another time that she faked passing out in her house, only to angrily jump off the hospital gurney because the paramedics were too rough, screaming, “How dare you f***ing morons handle me like a f***ing side of beef!”

Towards the end of the tour, Garland generously brought her manager onstage to duet with her, then aggressively shoved her back into the wings when it turned out Phillips could carry a tune. Garland’s life was a rollercoaster, and Phillips was screaming in the front car.

“Although the concerts were always wonderful, what came before and after was not,” Phillips wrote in her 2015 memoir, Judy & Liza & Robert & Freddie & David & Sue & Me (St. Martin’s Press). “Sometimes it was plain awful, and a few times almost tragic.”

One disaster nearly ended fatally for both women.

Garland was performing a two-week stint at the Sahara hotel in Las Vegas in 1962 and although her celebrity had faded, the hotel nonetheless put her up in the glamorous penthouse suite.

After her regular 10pm show, the buzzed star would either drag Phillips out for a night on the town that usually ended with steak and eggs at around 8am, or she would keep her fatigued manager awake in the hotel room playing gin rummy until the “20 or 30 pills” she took over the course of an hour made her fall asleep.

One game night, as the drugged-up Garland retired to her bedroom, she took a few steps and abruptly passed out, falling face-first onto the corner of the glass coffee table.

The brutal tumble cut her lip; the table went through her nostril, grazed her right eye and hit her forehead. As she lay there motionless, blood pooled at her head, soaking the carpet. Phillips was in shock and feared the worst.

“I bent over in a panic to see if she was breathing, way too scared to move or even to touch her,” she wrote. “Nevertheless, I tried to take her pulse. I was so scared. I could feel nothing. I had no idea if she was dead or alive.”

Terrified, she rang up the Sahara’s entertainment director, Stan Irwin, who was an expert in the destructive ways of addict performers. Irwin arrived fast with a doctor, who informed the two that Garland was merely sleeping, tranquillised to such an extent by the medications that the pain didn’t wake her up. He put her to bed and removed all the pills from the room.

A press release was drummed up chalking her upcoming stage absences up to “vocal strain”, and it was agreed she’d add a week of 2.30am shows when she recovered. All of this was decided while she was unconscious.

When Garland came to a few hours later, the Strip shook.

“Look at me!” she yelled at Phillips, who offered her some ice packs. “F**k the ice packs. Where’s my medicine? I need my pills, and I want them right now! Where the f**k did you hide them?”

Phillips insisted the doctor who treated Garland confiscated the pills, but the irate singer didn’t believe her. She walked into the kitchen, grabbed a large knife and lunged at her manager. “Would she have stabbed me? I don’t know,” Phillips wrote. “She was a raving lunatic at that point.”

Phillips, in her early 20s and spry, raced out of the suite and barricaded herself in her own hotel room, falling asleep for hours.

Later, she received a call from her boss, agent David Begelman, who happened to be having an affair with Garland. He told her the singer was deeply sorry and wanted to call to apologise. Why the change of heart? Begelman had arranged for a doctor to re-up all of Garland’s discarded meds.

Her life having just been threatened, Phillips wanted to quit. But “an hour and a $200 raise later, I agreed to have a conversation,” she wrote.

When Garland wasn’t pointing a knife at her manager, she was harming herself to get attention.

In 1963, during a concert-tour stop in Boston, Phillips and Garland were staying at the Ritz-Carlton hotel overlooking Boston Common. Generally, the singer preferred to get into costume for her shows in the dressing room at the venue. But on this night, she requested to change in her hotel suite.

When Phillips arrived to help, Garland abruptly slit her wrist mid-conversation.

“The moment was made even grislier by the fact that when she made the cut, she was looking at me and smiling,” Phillips wrote.

The shaken Phillips was wearing a brand-new outfit she treasured, made of light-coloured challis, but by the end of the messy incident, it was as red as ruby slippers.

The manager believes Garland’s many grisly suicide attempts were engineered to get the attention of her man du jour — in this instance, Begelman, her shifty agent and lover. Begelman rushed in from the room next door where he was staying and promptly called a doctor.

“He got there so fast, it made my mind spin a fiction that Judy had stationed him downstairs in the bar in advance for her own nefarious purpose,” Phillips wrote.

But despite sometimes sharing a bed with Garland, Begelman was all business. He instructed Phillips to dash to the store and buy enough bracelets to conceal the performer’s bandages. Garland, who had just tried to kill herself, would go onstage that night as planned.

“She did such a wonderful show, no one could have suspected she wasn’t at the top of her form,” Phillips said.

Although they were as dramatic a partnership as there ever was, Garland and Phillips got close. One time, nearly too close.

During a car ride, the manager claims she almost had a #MeToo moment — at the hands of the performer.

“Her hand began a trip from my knee, where she had placed it when the car lurched, to my crotch,” she said. “Her move wasn’t inadvertent. Judy did nothing inadvertently.”

Phillips, who was married and straight, completely froze, unable to speak. Garland’s hand was now fully groping her manager’s privates.

“The idea of being intimate with Judy revolted me. I wanted to reject her,” Phillips wrote. “Will I lose my job if I take her hand away? Will I offend her?”

Taking a breath, she grabbed Garland’s hand, placed it in the singer’s lap and smiled.

Garland moved on as if nothing untoward had happened.

When Garland died in 1969, Phillips lived just one block away from the Frank E. Campbell Funeral Home in Manhattan, where the star’s last hurrah was held. She did not attend.

“I couldn’t make myself go,” Phillips wrote. “I crossed Fifth Ave at one point and watched the line from a bench just outside Central Park and pondered the same things I had wondered about so many times in the past — mostly when I was watching her perform.

“How would that audience feel if they knew what I knew?”

If you or anyone you know needs help, contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Beyond Blue on 1300 224 636. In an emergency, call triple-0

This article originally appeared on The New York Post and was reproduced with permission