Film review: 127 Hours

WHAT sets British director Danny Boyle apart from every other mainstream filmmaker?

WHAT sets British director Danny Boyle apart from every other mainstream filmmaker?

I think I have the answer.

Most are sheepishly content to string an audience along with the promise of escapism.

Boyle emphatically ties up his audience by refusing to make any promises.

Let's call it no-escapism.

Look at Boyle's track record. He's had us hooked on heroin (Trainspotting), trapped on a kamikaze mission to the sun (Sunshine), stuck in a country populated entirely by infected mutants (28 Days Later) and holding on for dear life on the set of an Indian TV game show (Slumdog Millionaire).

Not surprisingly, there is simply no getting away from Boyle's latest film.

Adapted from Between a Rock and a Hard Place, the best-selling memoirs of American hiking enthusiast Aron Ralston, 127 Hours is out to move viewers with the tale of a man who cannot move at all.

In the spring of 2003, Ralston, an experienced solo outdoorsman, embarked on what he described in his book as an "impromptu weekend vacation" to the canyon country of eastern Utah.

Travelling first by all-terrain vehicle, then dirt bike and on foot, Ralston found himself late on a Sunday afternoon squeezing into a deep slotted crevasse more than 40km from the nearest road. Having assessed the stability of a 400kg boulder sitting across the mouth of the crevasse, Ralston scampered underneath and proceeded downwards. Due to the sudden movement in its vicinity, the rock decided to follow.

Twenty seconds later, Ralston had crashed to the bottom of the crevasse, with the boulder pinning his right arm to a craggy wall. Almost mischievously, Boyle signs off on this dramatic sequence - which occurs after only 15 minutes of running time - by flashing up the title of his film.

What follows in 127 Hours is an incongruously lively depiction of the macabre rut in which Ralston was forced to spend the next five days.

As you may or may not know - either state is perfectly fine on entering the cinema, by the way - Ralston had a decision to make during that period that would determine whether he lived or died.

The logistics were starkly minimal. The odds absolutely grim. Ralston had less than a litre of water for sustenance, and some very rudimentary tools to chip away at the rock. His arm had turned blue and would soon become gangrenous. Think about it - the only way out is unthinkable.

But before Ralston gets around to parting company with his arm using a blade no larger than your thumb, 127 Hours busies itself keeping pace with his racing mind.

Though Ralston's composure is unusually calm for someone in such a gruesome predicament, he is not above panicking or giving up.

However, it is where Ralston chooses to direct his thoughts during these moments of extreme duress that Boyle's film comes alive as inspired cinema.

There are flashbacks to better times with family and friends. Wrongs that may never now be righted. Fantasies and hallucinations of better times ahead. Which may never happen.

And via a diary Ralston records on his video camera, we receive running reports on what he is feeling - and refusing to feel - right there and then.

Ralston is played in 127 Hours by James Franco, a deceptively complex actor whose reading of his character does not conform to the default settings of performance many viewers will be expecting.

Scene by scene, Franco subtly strips Ralston clean of any sorrowful pause for regret, or burning need for redemption.

Focus on the honesty of Franco's work here, and you will see 127 Hours for what it truly is: not as a filmed ordeal about the loss of a limb, but a universal tale about the discovery of real resilience.

127 Hours (M)

Director: Danny Boyle (Slumdog Millionaire)

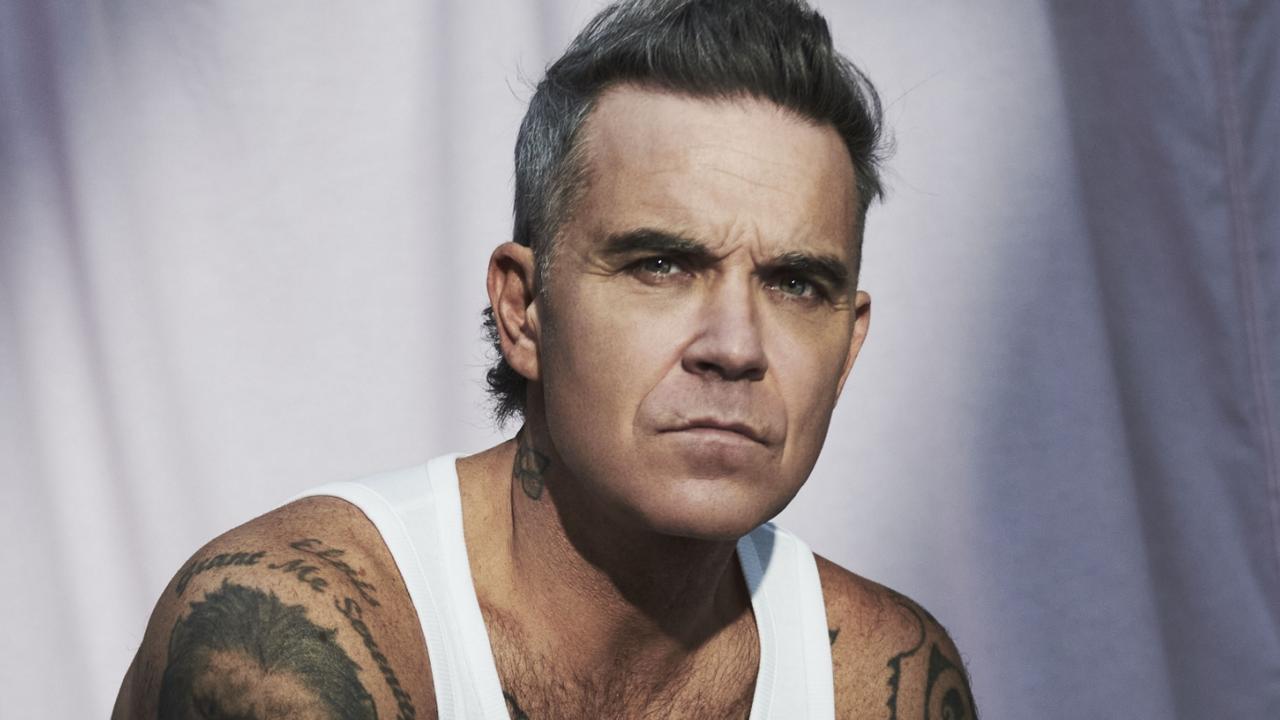

Starring: James Franco

4 stars

127hoursmovie.com