Princess Diana’s last phone call highlights a sad truth

It’s been 25 years since Princess Diana died yet her last phone call illuminates a sad relationship between four crucial players in her death.

OPINION

There’s a scene in the excellent new Diana documentary The Princess where the respected royal historian and author, Robert Lacey, is asked whether the engagement of Lady Diana Spencer to Prince Charles might ease some of the interest in the royal-to-be.

“I think we’re going to see a change in the attitude of the press,” replies Lacey in 1981 archival footage. “I think that now she’s palpably one of the royal family, all this telephoto lens business will stop.”

Lacey is not a dolt. He’s advised on royal history and protocol on hit TV series The Crown – yet his response shows the extent to which even the most qualified royal observers were blindsided by the rapacious interest in the new princess.

The fact is this “business” never stopped. As someone who witnessed it first-hand working for a British newspaper throughout the 1990s, the interest in Princess Diana – generated by the mutually parasitic relationship between public and press – only intensified.

The media didn’t kill Princess Diana but, 25 years to the day after I covered her death for a British newspaper, I now believe all of us did her wrong.

Equally, there is no question that Diana herself was complicit in feeding the voracious appetite for every image and detail of her life.

On this day a quarter of a century ago I was in the newsroom of the Daily Mail newspaper, just a stone’s throw from Kensington Palace, by 8am. For the next 15 hours as a vast team put together 80 pages of pictures and copy there was eerie silence.

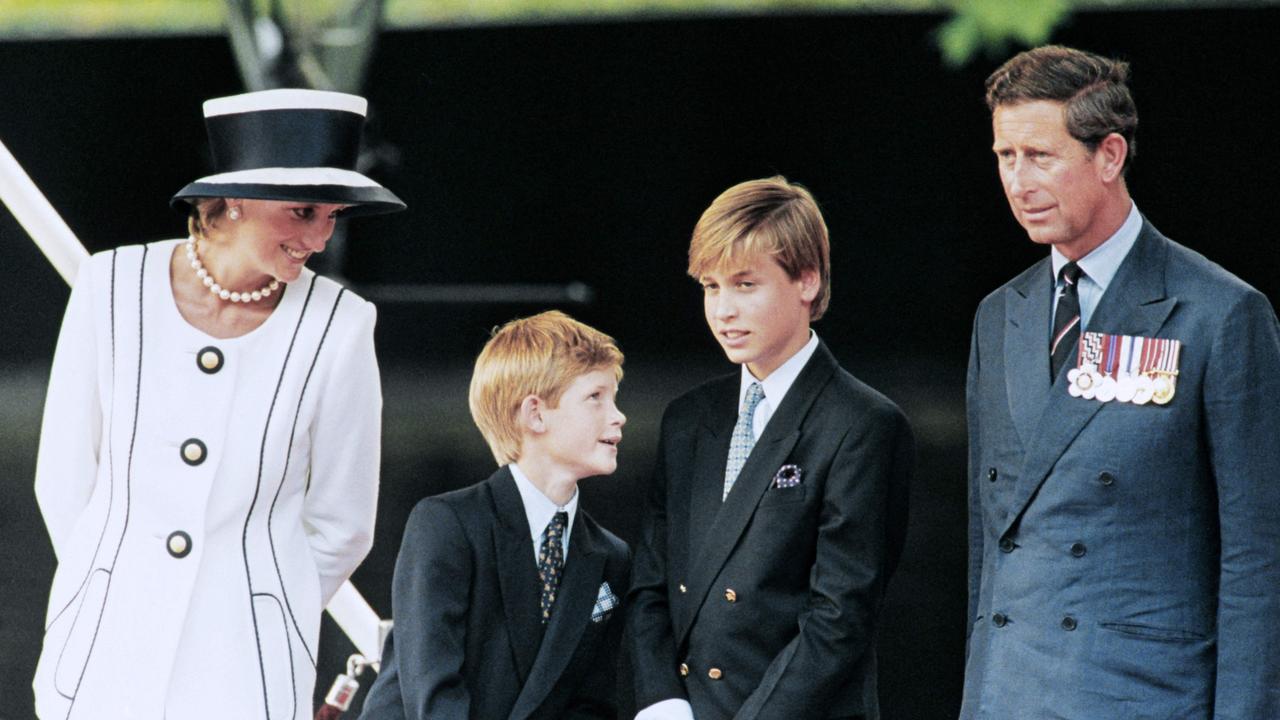

Our royal reporter, Richard Kay, to whom the Princess had made her last phone call before her death, was ashen. She had told him that she was looking forward to returning from holiday to see her boys and that she “wanted to explore a different kind of royalty”.

That conversation, in itself, illuminates the deeply intertwined and largely ungoverned nature of the relationship between press, public, palace and princess. And while today we may feel saddened by the loss of a compelling woman and an unquestionably devoted mother, we might also consider the part we played in her story.

If Princess Grace had primed us for that alluring axis of monarchy and celebrity, Diana became its poster girl.

She was youthful, compliant and endearingly shy but even at 19 she came with a complicated family history that could compete with Meghan Markle’s.

Her mother divorced her father when Diana was just seven and, as esteemed biographer Tina Brown would later explain, her relationship with her father, Earl Spencer, a keen photographer who had been awarded custody of his children, was built largely on the images he took of her. As Brown wrote: “[She] grew up associating the camera with love.”

That “love” is at the heart of the commodification of Diana. The public loved her because she was natural and delightful and was the first person to let in daylight upon the magic and mystique that is the royal family. Because the public loved her, the press clamoured to feed that adoration because it spelled profits.

A case in point: In the months following her death I was part of an investigative team of five, including Kay, who put together a glossy magazine which was included free with the paper every Saturday for 12 weeks. Sales increased by 400,000.

Yet there was no precedent for such interest and so both the palace and the press made it up as they went along. As the marriage between Charles and Diana disintegrated, the courtiers from their respective teams briefed against each other and in a pre-phone-hacking Britain, press coverage was largely unregulated.

To watch video footage of those years now is to be reminded of how unprotected Diana was in the face of an increasingly cavalier media – a photographer clamouring to get in a lift with her; her holding a tennis racket in front of her face while walking through an airport. If she was hung out to dry while within the royal family, she was completely vulnerable out of it.

In 1993, one newspaper published photographs secretly taken by a gym owner who’d set up a camera to take images of her working out. The Princess won a legal case to have all copies and negatives destroyed.

It’s no wonder she believed BBC journalist Martin Bashir when he showed her brother fake documents suggesting she was being spied upon.

And yet she, too, was a media manipulator and part of the sad and unethical spectacle. Unknown to anyone, she’d supplied biographer Andrew Morton with the tapes chronicling her eating disorder, suicide attempts and division with her husband that formed Diana: Her True Story.

One evening in 1994, I was in the newsroom and one of her aides contacted the newsdesk to tell how she’d helped save a drowning vagrant in Regent’s Park. In the War of the Windsors, public image was everything.

So have we learnt anything? To witness the Duchess of Sussex this week conflating her significance to that of Nelson Mandela, warning that she could “say anything” and claiming she couldn’t drop her son safely at school if she lived in England, you’d think not.

But three things have changed: Social media has put power back in the hands of the royal family; the Leveson inquiry into phone-hacking has reined in more dubious press practices and all of us – press, palace and public – are, for the most part, more cognisant of the pressures and responsibilities inherent in the circus that is fame.

Angela Mollard is a freelance writer.