Finding Freedom: Why Meghan Markle’s new book is a dangerous move

They’re said to be “relaxed” about imminent revelations regarding their private lives, but history proves Meghan and Harry have made a dangerous move.

She might have been dead for more than 30 years but we need to talk about Marion Crawford, a woman who did something so heinous, in the Queen’s eyes, that Her Majesty has reportedly refused to say her name since 1949.

The year was 1932 and the then-Duke and Duchess of York (Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret’s parents, later King George VI and the Queen Mother) needed a governess for their girls. Enter Crawford, a working class Scot who for the next 17 years would be at the very heart of royal life, a devoted, trusted and adored part of the family.

In 1948, Crawfie, as she was known, retired and such was her standing with the royal family, she was given her own lifelong grace and favour home in Kensington Palace.

And then the following year, she committed the cardinal royal sin: she authored a book about her time inside the most private confines of the Windsors. Despite the fact that Crawfie was devoted to the Queen Mother, Elizabeth and Margaret and her portrayal of them was deeply affectionate, she was immediately ostracised.

RELATED: Meghan and Harry’s book may cost couple $4.5 million

RELATED: Meghan move that ‘crushed’ Charles

With the publication of The Little Princesses, the first royal kiss-and-tell, Crawfie cast herself out in the wilderness and was immediately and irrevocably cut off from the family who had loved her so dearly. (To this day, any perceived disloyalty to the Windsors is referred to by the family as “doing a Crawfie.”)

The point is, royal tell-alls that betray the innermost workings of the royal family come at a price – and a steep one at that.

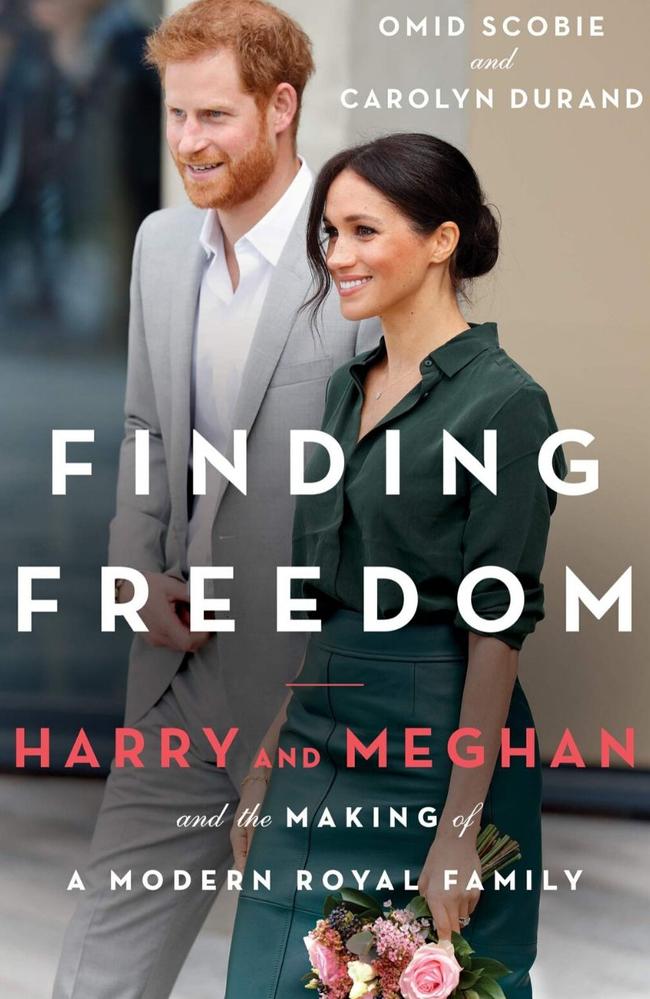

This week the latest royal biography hit the shelves after several months of feverish build-up, this time about the Duke and Duchess of Sussex.

Finding Freedom by royal reporters Omid Scobie and Carolyn Durand was announced in May with much fanfare, claiming it would go “beyond the headlines to reveal unknown details of Harry and Meghan’s life together,” offering “unique access and written with the participation of those closest to the couple.”

To be clear, both the authors and the Sussexes have strenuously denied that the royal couple were interviewed for the book nor is it an authorised or endorsed biography. However, Scobie and Durand have spoken to 100 sources including “close friends of Harry and Meghan’s, royal aides and palace staff (past and present)”. In May, a spokesperson for the couple said they were “relaxed” about this.

The prevailing wisdom is that for Harry and Meghan, having two writers who are seemingly sympathetic to their travails presenting the Sussexes’ side of the events that lead up to their sensational exit from the royal family would be a sure-fire PR boon. Release the book and cue an outpouring of public sympathy.

The world got its first taste of what is in store when extracts from the book were serialised in The Times in late July, with the inclusion of a number of highly personal details such as that Meghan FaceTimed a friend from the bath the night before the wedding or the yoga pose she adopted after the subject of marriage first came up with Harry, thus raising more than a few eyebrows about how Scobie and Durand might have gleaned such intimate details. (“However much the Sussexes distance themselves from the book, it reads like a ghostwritten autobiography,” the Times’ royal correspondent Roya Nikkhah recently wrote.)

But here’s the thing: Opening the doors to royal life and letting the prying, intrusive public in to nose around comes at a price.

For proof, look no further than Harry’s parents Prince Charles and Diana, Princess of Wales.

By the time the ‘90s had rolled around, and after nearly a decade of miserably coexisting in a crumbling marriage, things inside Kensington Palace were combustible.

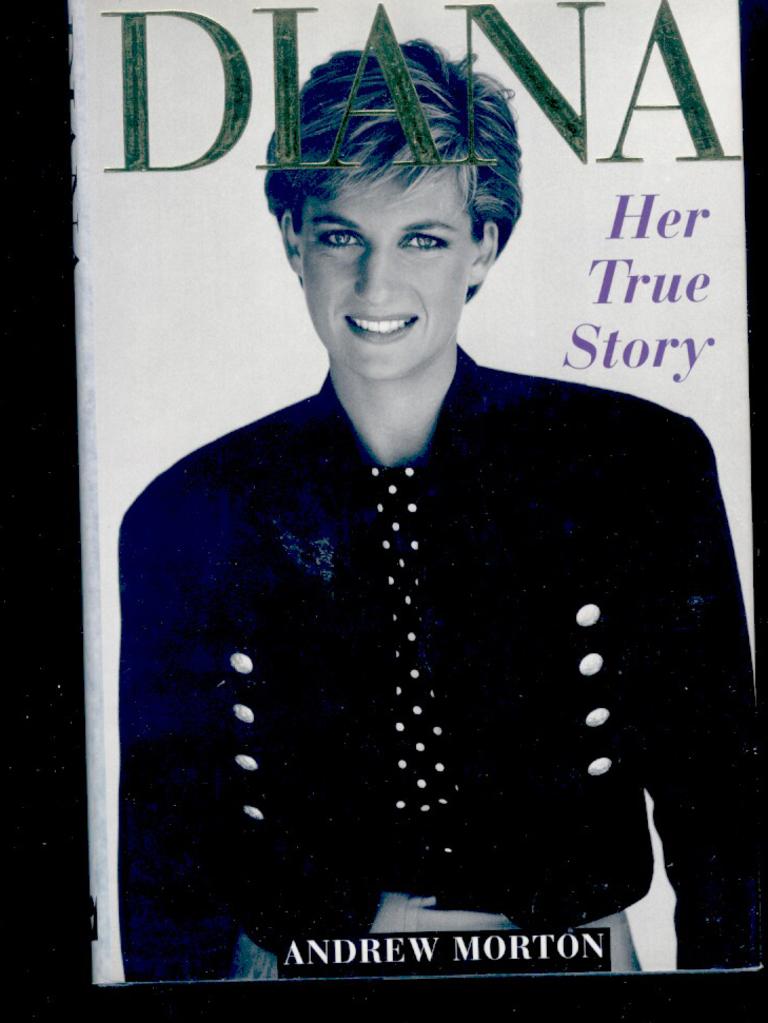

Desperate to tell the world just how much she had suffered, in 1991 Diana, using mutual friend James Colthurst as a conduit, agreed to open up to royal reporter Andrew Morton. The following year in June, excerpts from Morton’s Diana: Her True Story were serialised in the Sunday Times, with the headline “Diana driven to five suicide bids by uncaring Charles”.

The effect was as if a nuclear bomb had been detonated in the Throne Room. Both Charles and the Queen’s images were seriously battered, the duo cast as deeply uncaring in the face of Diana’s suffering.

Republican sentiment jumped. Six months after Diana crossed the royal Rubicon, the separation of the Wales’ was announced in parliament.

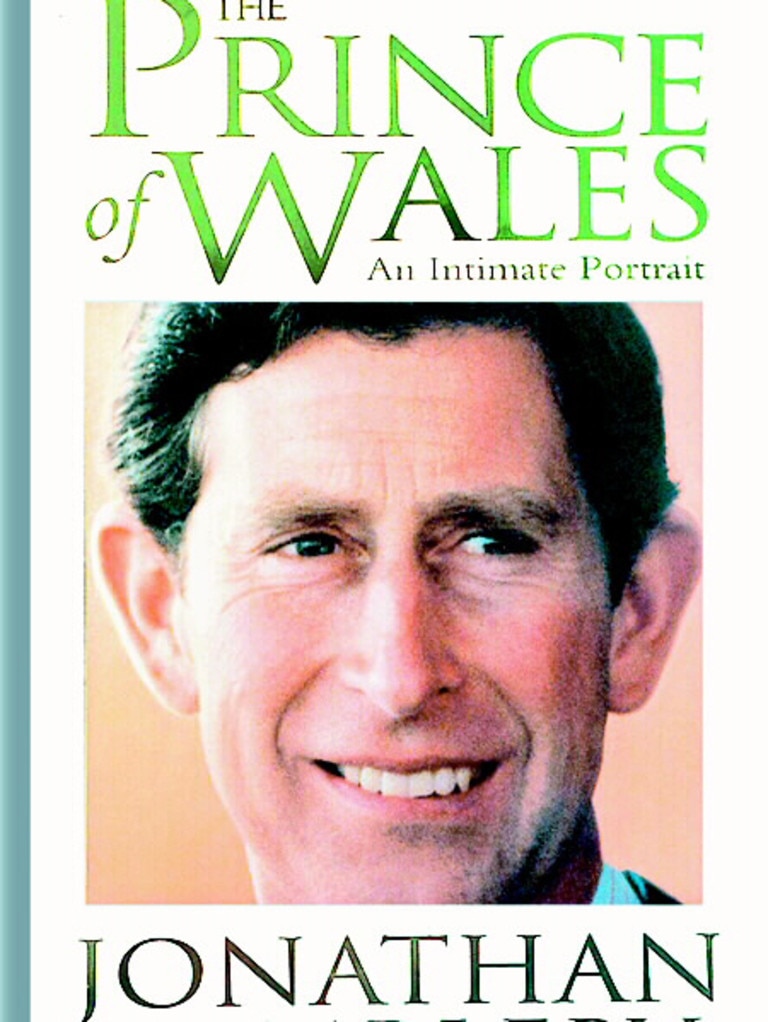

Two years later it was Charles’ turn. While Diana’s involvement with Morton’s book would only be confirmed after her death in 1997, the Prince of Wales gave his blessing to journalist Jonathan Dimbleby’s 1994 book, The Prince of Wales : An Intimate Portrait.

It revealed Charles had never loved Diana and had felt pressured into marrying her. The Wales’ marriage “has all the ingredients of a Greek tragedy … I never thought it would end up like this,” Charles opined to Dimbleby.

(Three months earlier in a TV interview with Dimbleby, Charles had also sensationally admitted that he had been unfaithful to Diana.)

While there is a certain admirable quality to Charles’ brutal, masochistic honesty, like Diana two years earlier, his admissions rocked the establishment. His public standing cratered and a poll done by The Sun newspaperfound two thirds of respondents thought he was unfit to be King.

In both the cases of Diana and Charles it is easy to understand why they did what they did. (As esteemed Diana biographer Tina Brown has written: “The Morton book was Diana’s most elaborately mounted expression of choreographed rage.”)

As the War of the Wales played out on the front pages of the nations’ newspapers, both were fighting to claim the mantle of victimhood once and for all. Angry, hurt and desperate to win the public image war, first the Princess and then her husband resorted to the nuclear option and revealed their cards in the most public way. Both attempted to ‘own’ the narrative and in doing so, both damaged their reputations.

The biggest takeaway of the whole unedifying situation might be that chasing public sympathy is a risky business, liable to blow up in one’s face.

For Diana, Morton’s book significantly damaged her already frayed relationship with the Queen and set in motion a series of events that would ultimately lead to divorce. For Charles, his very suitability to be the next monarch was widely called into question, his involvement with Dimbleby imperilling his chance to be King.

What we have seen of Freedom so far would suggest that this is far from a PR slam dunk for the Sussexes. The couple, we are told, were distrustful of palace courtiers (or the “the vipers” as they allegedly call them) and frustrated that their headstrong zeal to do things their own way was rebuffed by the tradition-bound palace machine.

William is accused of being “snobbish” for urging Harry to take his time with Meghan and Kate is portrayed as cold for failing to extend the hand of sisterhood and not taking her future sister-in-law shopping. Hardly incendiary stuff.

However, the book has also aired a number of claims that are far from flattering for the duke and duchess. Meghan, we are told, used to occasionally set up paparazzi pictures prior to her relationship with Harry. He comes across as thin-skinned and they both seem resentful of their royal lot.

Whether Finding Freedom will send shockwaves through the palace a la Morton and Dimbleby’s explosive opuses or whether the entire thing will be a bit of a damp squib (sound and fury signifying nothing much beyond Amazon sales) remains to be seen.

Likewise, will there be consequences for this breaching of the clannish sensibilities of the house of Windsor?

More than 70 years on from the publication of Crawfie’s The Little Princesses one thing has not changed: Any book that lets the light in on the magic of the royal family, to paraphrase the famous Walter Bagehot line, is a dangerous undertaking – especially for an HRH.

Daniela Elser is a royal expert and writer with more than 15 years experience working with a number of Australia’s leading media titles.