The Aboriginal Soccer Tribe

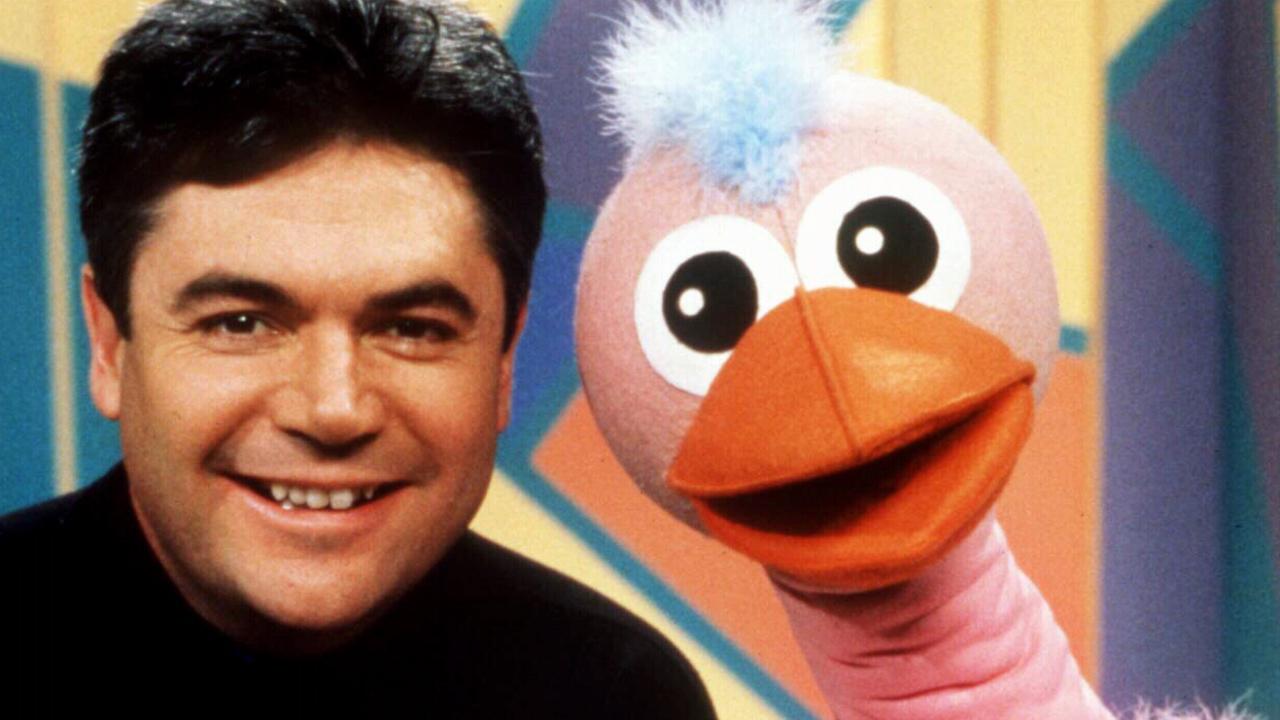

FORMER soccer player John Maynard, explores the ins and outs of Australia's Indigenous soccer players.

ADAM Goodes and Johnathan Thurston are not merely Aboriginal success stories, they are footy superstars who have left an indelible mark on their respective codes.

Indeed, the AFL and NRL are so adept at cultivating indigenous players, they surely have lessons to teach other professions and sports in which Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders are under-represented.

Take Soccer. Compared with Australian football and rugby league, indigenous participation in the beautiful game is low; the story of Aboriginal players' contribution little known.

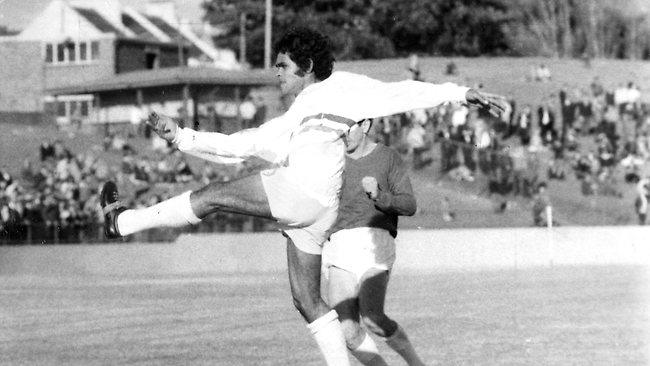

Indigenous academic and former soccer player, John Maynard, sets out to redress the imbalance in this timely, engaging book. The Aboriginal Soccer Tribe documents and celebrates the achievement of several generations of Aboriginal soccer players who, especially during the protection and assimilation eras, often found greater acceptance on the pitch than in the outside world.

One of Maynard's central arguments is that Aboriginal players were more at home within postwar migrant soccer teams than in mainstream society; a case of two marginalised groups finding common purpose in the round ball. In the early 1960s, when the indigenous activist, Charles Perkins, was captain-coach of local club Pan Hellenic, he was his team's only Australian-born player. During Maynard's childhood in regional NSW, soccer was routinely disparaged as "wogball".

The Aboriginal Soccer Tribe offers potted biographies of leading indigenous players, from the old guard who played in the 1950s and 60s -- Perkins, John Moriarty and Gordon Briscoe -- to past and present Aboriginal Socceroos Harry Williams, Kasey Wehrman, Jade North, Travis Dodd and David Williams.

Bondi Neal, a young miner based in Newcastle, was thought to be the first Aboriginal soccer star, goalkeeping for teams in that area in the early 1900s. Soon after, state protection boards corralled Aborigines into reserves and missions, cutting them off for decades from the chance to pursue professional sports careers.

Maynard's book is in part, a timeline of oppressive government policies foisted on indigenous people. In 1960, Moriarty -- who that year became the first Aborigine to be selected to play soccer for an Australian national team -- had to seek permission from the Protector of Aborigines to travel interstate with the South Australian side. This stirred Moriarty's awareness of institutional racism, and like Perkins, he would evolve into a well-known rights activist.

Maynard profiles emerging soccer talents such as Adam Sarota and James Brown, and the Aboriginal Matildas.

While Harry Williams and North are the two most-capped Aboriginal Socceroos, a woman, Bridgette Starr, is the most capped indigenous international, having represented Australia 53 times. Former Matilda Karen Menzies grew up in foster care and had no idea her birth mother was Aboriginal until she was 16. The discovery knocked her sideways, but she went on to play for Australia and to work for the Human Rights Commission's Stolen Generations inquiry.

Some Aboriginal players who showed great promise never made it. Maynard attributes this to injury, bad timing, lack of support from the code.

Here, his analysis can be thin, as he underplays the obstacles a severely disadvantaged, dysfunctional community or family can pose for even the most talented athlete.

Soccer finally captured the Australian public's imagination in 2006 when the Socceroos qualified for the World Cup finals in Germany. According to Maynard, the professional game's rising popularity since then has paralleled an increasing indigenous presence. However, Aboriginal participation rates still lag behind those in the AFL and Australia's Football Federation has introduced a 10-year plan to address this. Maynard argues, convincingly, that more needs to be done.

He recounts stories of hundreds of Aboriginal children from rural Australia being switched on to the world game.

In 2009, the Northern Territory's Borroloola Cyclones -- an all-Aboriginal team from a tiny, remote community -- caused an upset when they thrashed the Territory's under-16s team at Darwin's Arafura Games. But, as Maynard observes, such accomplishments reflect the vision of dedicated volunteers, rather than any co-ordinated recruitment drive.

The Aboriginal Soccer Tribe is an overdue and important book. It shines a high beam on the often poorly illuminated achievements of indigenous soccer players who represented their clubs, states -- and in many cases, their country -- with distinction.

The Aboriginal Soccer Tribe: A History of Aboriginal Involvement with the World Game

By John Maynard

Magabala Books, 192pp, $24.95