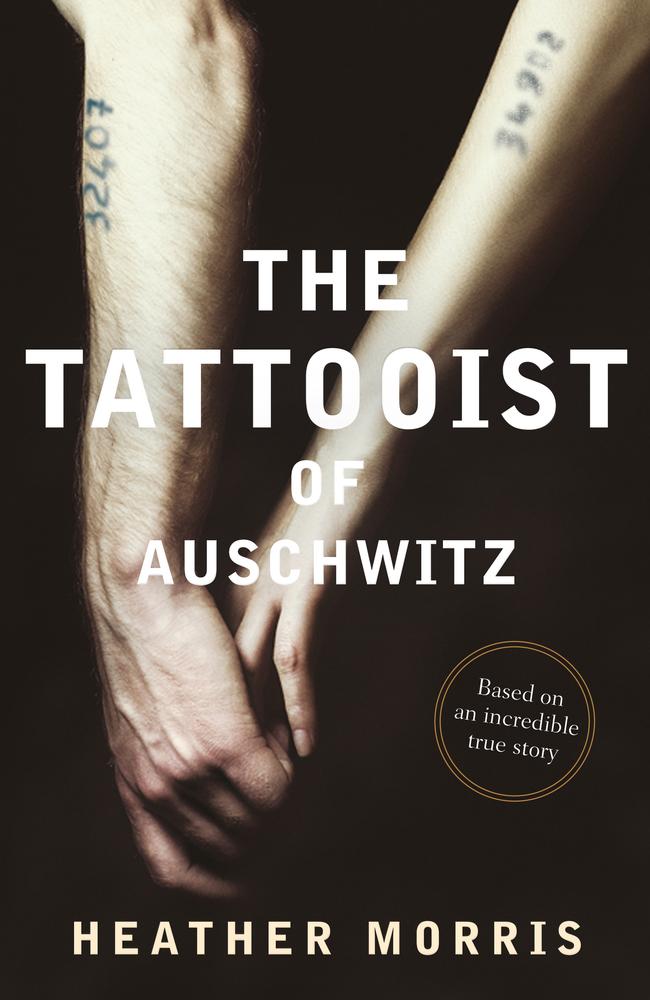

The incredible secret love story of the Tattooist of Auschwitz

AMID the inhumanity of the grim death camps of Auschwitz, Lale Sokolov was determined to survive. Incredibly, prisoner 32407 also found a love that survived the Holocaust.

FOR more than 50 years, Lale Sokolov stayed silent about a lot of things.

The only evidence then that the world could see of the horror 2 ½ years he spent at World War II’s most notorious Nazi death camp were the faded, roughly-inked numbers tattooed on his forearm.

They gave no clue to his experience, or his role at Auschwitz at the hands of Hitler’s SS.

Lale, the Auschwitz Tattooist, carried survivor’s guilt and guarded his secret well.

His son knew not to ask about it and just listen when, after years of silence, the stories began to be shared.

Lale was also guarding an incredible love story ignited against the grim background of the gas chambers, with one of the women he was forced to ink.

Against all odds, the pair escaped the death camps to share a better life.

Lale’s transformation from Jewish prisoner to chief tattooist at Auschwitz stalked him into his old age. Terrified he’d be seen as a Jew who had worked for the Nazis to save himself, he carried shame and guilt inside.

His greatest regret, he once told his son, Gary, was “the people I couldn’t save”.

Lale’s story, and that of the woman he inked who would become his wife, is now being told in a book, The Tattooist of Auschwitz.

It’s a horror story, and a love story. And Lale’s legacy.

“WELCOME TO AUSCHWITZ”

Ludwig (Lale) Eisenberg (he would later change his name to Sokolov) was born in 1916 in Slovakia. He was well-dressed. A charmer. A ladies’ man. He loved to travel.

He was also a Jew. So Hitler’s war changed everything.

He was just 24 when, in April 1942, he was herded with hundreds of other Jews like cattle into a dark, cramped railway cargo carriages.

After two days, the doors opened.

The prisoners emerged: stinking, thirsty, weak, cramped and hungry, to find German soldiers barking orders at them. Dogs barked menacingly at their sides.

Some were belted with rifle butts for moving too slowly. Others were berated and attacked as their scant possessions were taken from them.

As a gunshot rang out, Lale heard the cruel words: “Welcome to Auschwitz”.

They took his name and shoved a piece of paper with the number 32407 written on in into his hand.

Minutes later, the numbers were crudely tattooed in green ink into his left forearm.

It took less than 10 seconds to become a number in a Nazi death camp.

When Lale was struck down with typhoid, he was saved by Pepan, the man who had tattooed him. He dragged Lale inside and cared for him after he was pushed off a death cart.

The job offer, when it came, was simple, an extract from the book reveals.

“Would you like a job working with me?” Pepan asked. “Or are you happy doing whatever they have you doing?”

“I do what I can to survive,” Lale replied.

Surgical, Pepan said, lay in the job offer.

“You want me to tattoo other men?” Lale asked.

“Someone has to do it,” Pepan replied.

GRIM TASKS, AND LOVE

Lale chose survival. He inked fellow prisoners for three years.

Tattooing prisoners was unique to Auschwitz, and was introduced when the death toll in the fields, and gas chambers became so large it became impossible to identify bodies.

The tattoos would become one of the most sobering, recognisable symbols of the Holocaust.

Prisoners put to work at the concentration camps were inked on arrival. For those that didn’t, it was straight to the gas chambers.

It was the grimmest of tasks. But it found Lale the woman he loved.

Gisela Fuhrmannova — Gita — was sent to have a fading tattoo redone. The Nazis wanted to make sure the ink was permanent.

As he re-inked the number — 34902 — Lale held her arm for a second longer than he had to, meeting her eyes.

He spotted her again a few days later, head shaved, draped in prisoner black. Her eyes captivated him.

As Tätowierer (Tattooist), Lale was a prisoner of slightly more value to the Germans. It was enough for the pair to risk a clandestine courtship: secret letters smuggled between the men’s and women’s dormitories.

Love blossomed against a background of inhumanity, death and danger.

Lale’s guard, cruel and knowing, relished having Lale’s fate in his hands.

He would taunt him. Terrify him. Remind him constantly death was not far away, a book extract reveals.

Meanwhile, Lale tattooed his fellow prisoners, unable to meet their eyes. He feared some would think he had chosen to serve their jailers, and become a Nazi collaborator to save his own skin.

Another SS officer made sport of holding a gun to his head. He knew a bullet would be better than the gas chambers.

At one point, Lale was forced to enter those chambers — a nightmarish, macabre tangle of hundreds of naked bodies. Now he knew death smelled like blood and urine and excrement and other things he couldn’t identify, but would never forget.

As he left the chamber a guard cruelly said: “You know something, Tätowierer? I bet you’re the only Jew who ever walked into an oven and then walked back out of it.”

ESCAPE

As the Germans lost their grip on the war, Lale and Gita were separated — sent to different camps as prisoners were shipped out of Auschwitz.

When the war ended, a stubborn Lale went to the main train station in Bratislava. He couldn’t know if she was alive or dead as he scanned the crowds of emaciated prisoners disembarking.

It took a fortnight before Gita’s gorgeous eyes found his.

They married in October 1945, and eventually migrated to Melbourne where Gary, their only child, was born in 1961.

They tried to forget, but could never escape the nightmare of the Holocaust.

Not that young Gary would have known. He remembers a childhood surrounded by love, and warmth and joy.

“Dad was generous, kind, loving and always telling me to ‘try everything because we missed out. You have to do it, or you mightn’t get a chance’,” Gary says.

The house was full of kids and visitors and laughter and food.

“There were only three of us but on Friday nights mum would make 20 schnitzels, just in case people dropped in,” Gary says.

The tattoos were a visible reminder of far worse times.

The first Gary knew of his parents’ survival in the camps came when he was aged between seven and 10. They asked him to watch a documentary called World of War.

They couldn’t bear to watch it with him.

“Anything on the Holocaust, they wouldn’t watch,” he says.

“But once I’d watched it, that’s when my Dad started to tell me.”

The stories came sporadically, never in sequence. Gary soaked up the snippets. But knew instinctively to never ask more.

“He’d tell a story and then he’d move on. It wasn’t a question-and-answer session,” he says.

It took Gary a month to read the book.

“I read the first page and then I did not pick it up again for three or four weeks,” he said.

“Even though I knew most of the stories ... to have them all in chronological order, just seeing it all there, it was just really, really hard.”

It’s the same reason Gary has tried to go to Auschwitz three times in the past 15 years — but turned around at the border every time.

“It’s just too raw. But the feeling when I stand there is I’m terrified it would make it that much more real,” he says.

“At the moment it’s still stories. To actually walk through the gates … it’s a bit too confronting.”

“A BEAUTIFUL LOVE”

Gita wasn’t into discussing the past. She had her tattoo removed 10 years before she died.

Lale kept his, testament to his pride that he had survived “and determined to outlive every single German soldier that was involved in the war”.

“I think Mum just wanted to remove herself from anything about that time that happened in her life,” says Gary.

Anything, that is, except her beloved husband.

It was, Gary says, “a beautiful love”.

“She adored him, he protected her. He knew whatever happened, as long as they were together, he could cope.

“When she got sick, the level of devotion ... day in, day out ... there was nothing more important to him than just sitting with her.

“She was the most beautiful person in the world to him, always,”

The first and last time Gary saw his father cry was in 2003, after Gita succumbed to heart problems, aged 78.

After the tears dried, Lale started to tell his stories for the book.

“It was like he needed to tell it now, because his wife was waiting for him,” Gary says.

Three months after Gita died, Lale was operated on for the same heart issue which had claimed her.

The surgery brought him another three years.

Time enough to tell his story. And then, in 2006, go to join his wife.

The Tattooist of Auschwitz by Heather Morris (Bonnier Publishing Australia, $30) is out on February 1.