Matthew Flinders’ epic voyage to save 80 men and one cat after being wrecked and left to die

One legendary cat, several farm animals and 80 seafarers faced death after being abandoned in the open ocean – until an extraordinary man hatched an audacious rescue plan.

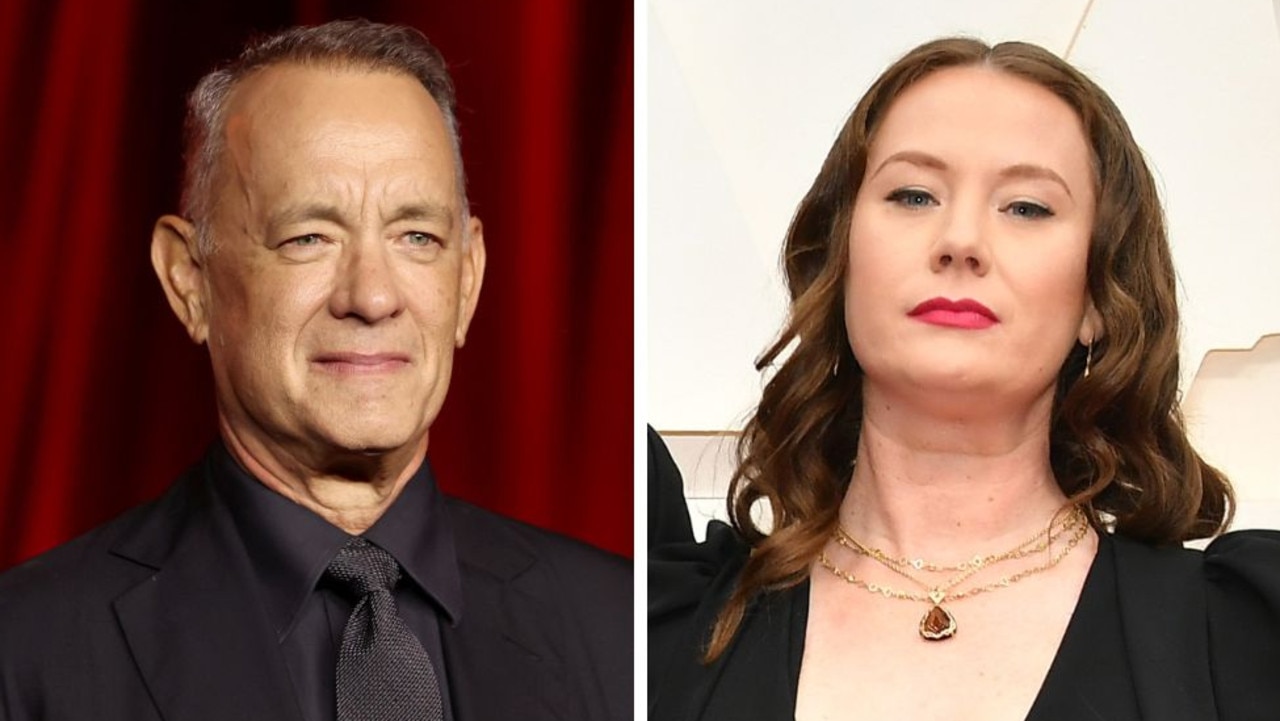

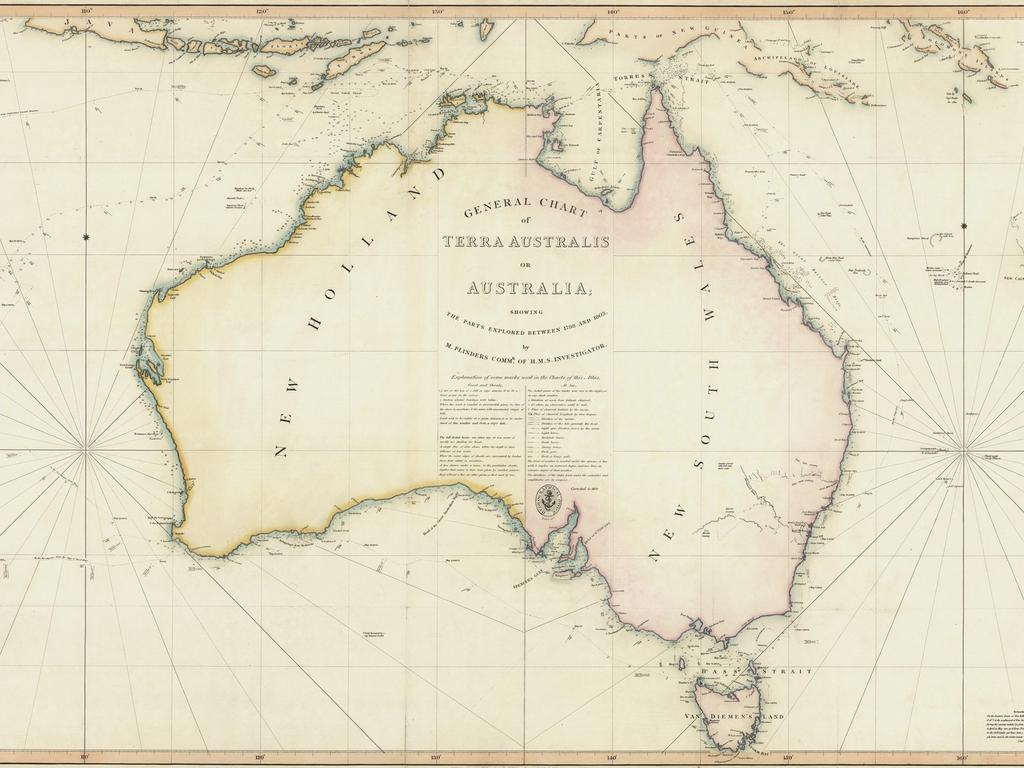

Matthew Flinders is known as the man who put Australia on the map – literally. In this edited extract from a new biography of the famed sailor, explorer and cat-lover, GRANTLEE KIEZA tells how Flinders pulled off an extraordinary feat to save his men (and his beloved pet) when disaster struck.

Having completed the circumnavigation of the great land mass he named ‘Australia’ and having proved at last that it was an island continent, Matthew Flinders and his men said goodbye to Sydney just before noon on 10 August, 1803. They were farewelled amid a festive atmosphere, with Governor Philip Gidley King waving them off.

Flinders was sailing home as a passenger on the ship Porpoise, working on his notes and his charts of the Australian coastline to present to the British government. The Porpoise, was heading north for Timor in a convoy with two other vessels: the Bridgewater and the 450-ton Cato.

Amid fair weather and light breezes, by August 17 they were about 200 kilometres east of what Flinders called the ‘great Barrier Reefs’ and sailing on through the night.

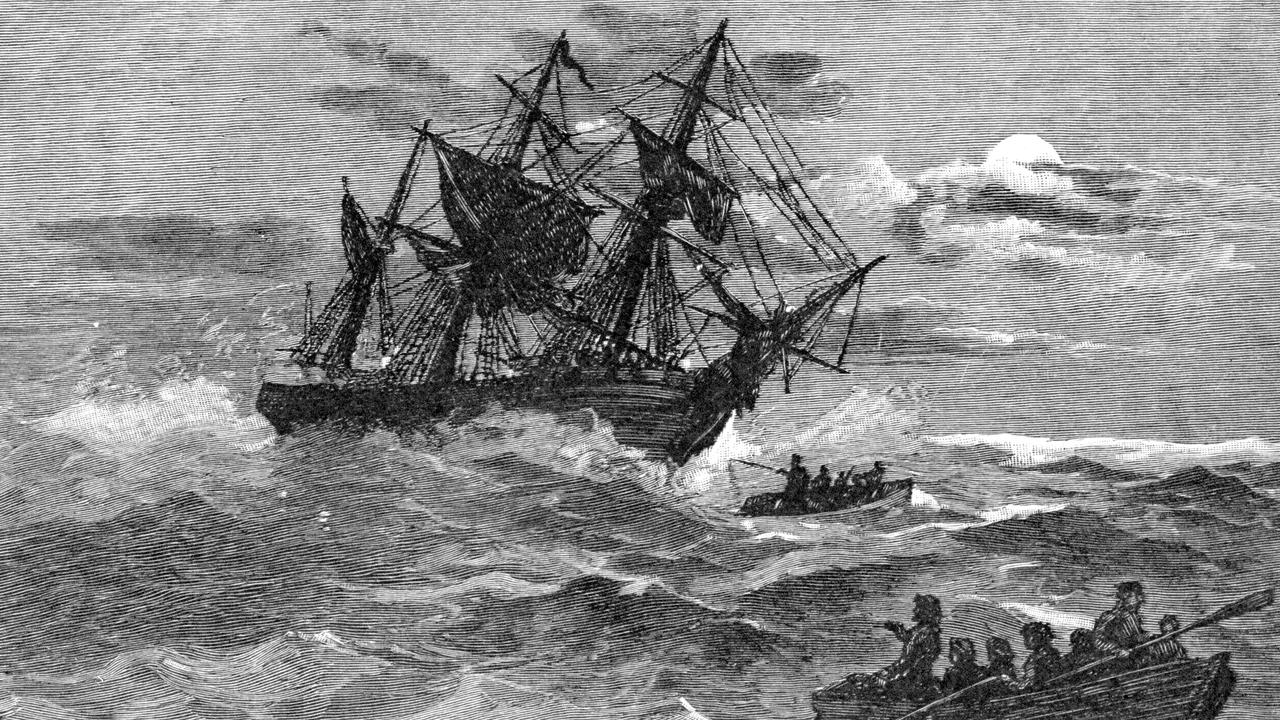

At 9:30pm, in the pale moonlight, two men at the same instant cried out that they saw surf ahead ‘only 50 yards away’. The coral reef showed itself in a long line of foam in the gloom of night. Then the Porpoise was sucked in among the raging breakers and, crashing into coral, was flung onto its side. Screams and groans echoed around the disabled vessel and young artist William Westall despaired that ‘not a possibility appeared that anyone could be saved’ as the ship’s bottom caved in and the hold quickly filled with water.

Skipper Robert Fowler did his best to rally the men. ‘Come, my Lads,’ he bellowed, ‘I have weathered worse nights than this!’ But at the second or third shock of the great waves the foremast was ripped off and carried away. The crew tried to fire a cannon to warn the other ships and set warning lights, but it was impossible in the chaos.

Then Matthew gasped in horror as the Cato slammed into the reef. The ship fell over on her broadside, and almost instantly the masts sheared off and disappeared.

In the distance, there was a light on the masthead of the Bridgewater. For a moment Matthew thought that its captain, E.H. Palmer, would tack and send boats to rescue the stricken men. He quickly realised, though, that such an operation at night would mean ‘certain destruction’.

Matthew had no idea how long the Porpoise, ‘being slightly built and not in a sound state’, might hold together, but the men managed to free the smallest of its boats, a four-oared gig.

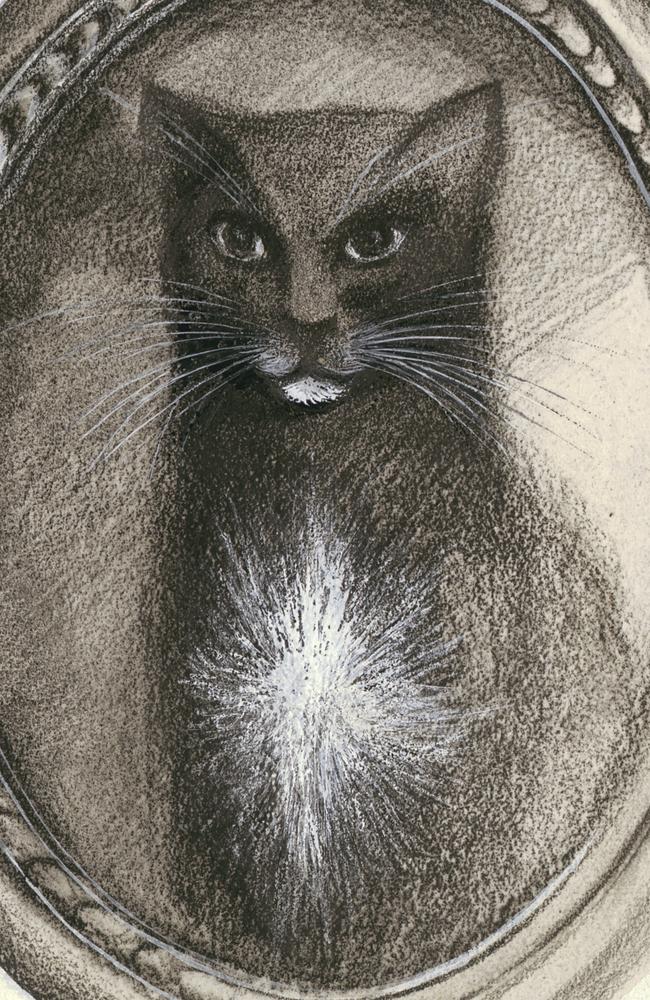

Matthew planned to wrap his charts and logbooks into a seal skin, take the small boat to the Bridgewater and then use its boats to get the people off the reef as quickly as possible. He checked that Trim, his famous black cat, was safe as Fowler organised men to row.

Bailing water and pummelled by the sea, they rowed towards the Bridgewater’s light, but the vessel was not slowing down. The light grew more distant, until finally it disappeared from view.

The darkness prevented any hope of communication with the men on the Porpoise until morning, by which time Fowler had started his men on making a raft. He organised for blue lights of distress to be burnt every half-hour but the Bridgewater did not come back.

And so the crew of the Porpoise spent this traumatic winter’s night in the boats or hanging onto the raft, shivering and shaking. Their ship creaked and groaned in its death throes as each wave delivered another merciless blow. Crewman Samuel Smith wrote that in this ‘mizerable situation’, every heart was ‘fill’d with Horor, continual seas dashing over us’.

In the distance, the Cato was still being shredded, the wild surf hammering it into the coral. Everything except the forecastle and bowsprit was submerged. Terrified men, including the skipper John Park, clung to the wreckage yelling for help while the surf beat them incessantly toward the swirling deep.

As the sun rose, the men saw the faint outline of the Bridgewater coming towards them.

Matthew spotted what appeared to be a dry sandbank, not more than 800 metres away, which looked large enough to accommodate all the men and what provisions they could salvage.

He took the gig to the sandbank, and the sight of many seabirds’ eggs scattered over it showed that it was above the high-water mark. He sent the gig back for Fowler, then hoisted two handkerchiefs on a tall oar to alert the Bridgewater.

But by 10am the Bridgewater had changed course and disappeared from view. Matthew and his shipwrecked men were staggered.

Fowler sent a boat to the stricken Cato to begin ferrying men to the shallow water around the Porpoise. Several of the Cato’s crew had been badly injured and three young lads had drowned.

Low water came about 2pm, and with the reef dry next to the Porpoise, the men frantically got together provisions, clothes and Trim the cat, and began ferrying them to the sandbank. By twilight, five casks of water, some flour, salt meat, rice and spirits were landed, along with the pigs and sheep that had escaped drowning. All the surviving men from both ships had made it ashore.

Even in the eye of the storm, Matthew was watching out for his beloved pet. ‘The imagination can scarcely attain to what Trim had to suffer during this dreadful night, but his courage was not beat down,’ Matthew wrote later.

***

With the blessing of Fowler and Park, Matthew took command of the situation. He promised food for the men who worked hard and floggings for shirkers, exempting only the eight badly injured men from the Cato.

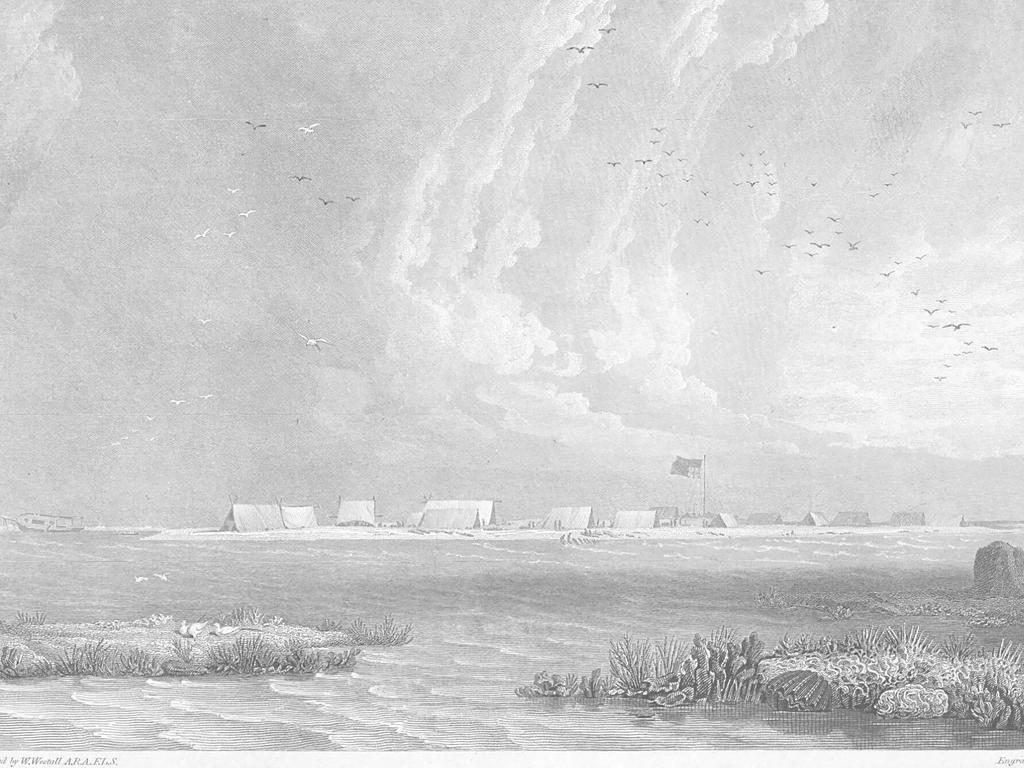

Matthew ordered a topsail yard that had survived the catastrophe to be erected as a flagstaff on the highest part of the bank, and a large blue ensign was hoisted upside down as a distress signal to the Bridgewater. Matthew expected that if no accident had happened, Captain Palmer would come to save them as soon as the wind moderated, but he judged it ‘prudent’ to act as if no help were coming. That proved to be the right course, as he later wrote:

Captain Palmer had even then abandoned us to our fate, and was, at the moment, steering away for Batavia, without having made any effort to give us assistance. He saw the wrecks, as also the sand bank, on the morning after our disaster … he neither attempted to work up in the smooth water, nor sent any of his boats to see whether some unfortunate individuals were not clinging to the wrecks, whom he might snatch from the sharks or save from a more lingering death; it was safer, in his estimation, to continue on his voyage and publish that we were all lost, as he did not fail to do on his arrival in India

Palmer would later say that he didn’t believe anyone could have survived the wreckage he saw, and the danger to his own ship was too great to investigate – an explanation Governor King blasted as ‘very lame’, especially since the Bridgewater’s third mate later wrote that the two wrecked ships were ‘distinctly seen’, and he was convinced ‘that the crews of those ships were on the reefs’. After reaching Batavia, Palmer sailed the Bridgewater for India then on to England, but the ship was never seen again.

On what became known as Wreck Reef, Matthew’s men spent four days in the boats transporting all the food, water, wine, spirits and porter to the sandbank, where it was placed in a large tent made from rescued spars and sails. Matthew calculated there was enough food and water to last them three months. Trim was put in charge of eliminating vermin in the stores and his ‘zeal in the provision tent’ was admirable.

A row of tents was erected, and although most of the men worked tirelessly for mutual benefit, Matthew had one of the freed convicts whipped at the flagstaff for ‘disorderly conduct’, and ‘to correct any evil disposition’ among the others.

By 22 August, Matthew realised the Bridgewater was gone for good. He called a council of his officers to decide how they might rescue themselves.

***

The largest cutter was made ready for the most dangerous expedition of Matthew’s life. Eighty sunburnt, hopeful men and one active black cat on this tiny sandbank hundreds of kilometres from help gathered around him and his intrepid team on the morning of Friday, 26 August 1803.

It was only a few weeks since Matthew had sailed into Sydney Cove in triumph after his great voyage around the entire coastline of Australia, and now he was embarking again under far different circumstances, with many lives dependent on his success. Matthew named the little cutter the Hope.

The morning was fine, and the wind light from the south. He had John Park on board and a double set of rowers, twelve men, to propel them all the way to Sydney when there was no wind for the sail. They had three weeks of provisions and two casks of water, meaning the Hope was ‘loaded rather too deeply’.

At eight in the morning they pushed off, to three cheers.

They sailed westward in the lee of the reef before reaching two more sandbanks. They stopped at a third one to cook a meal onshore, and Matthew shot as many noddies as he could to feed the men. They then rowed into the open sea and headed southwest for Sandy Cape, 305km away, on the edge of Hervey Bay. For a while the little vessel was surrounded by playful humpback whales.

The wind died and the men rowed slowly through the still night, making about eight kilometres an hour.

That afternoon, the wind picked up speed alarmingly, and Matthew realised the cutter was carrying too much weight.

[T]he increased hollowness of the waves caused the boat to labour so much, that every plunge raised an apprehension that some of the planks would start from the timbers.

Having no other resource, we emptied one of the two casks of water, threw overboard the stones of our fire place and wood for cooking, as also a bag of pease and whatever else could be best spared …

They saw land to the west, about twenty kilometres away, at sunset on the third day of the voyage, and they then turned south, parallel to the coast. By daylight on 29 August, Matthew could make out the tops of trees somewhere between Double Island Point and Moreton Bay.

The breeze died away that afternoon, and his men took to the oars before seeing Cape Moreton at sunset. Rain poured during the night, drenching them, but they were near the halfway mark of their journey.

At Point Lookout, they saw about twenty men of the Quandamooka people performing dances for them in imitation of the kangaroo. Matthew made signs for water and they pointed to a small stream falling into the sea. Two of the sailors leapt overboard, with some gifts for the Quandamooka and hauling one end of the lead line, to which was tied the empty water cask.

The Quandamooka stayed away from these intruders, but a shark had followed the swimmers to the beach. Fearing they might be attacked, Matthew hauled up the anchor and they rowed closer to the shore. The cask of water, a bundle of wood and the two men were soon back on board.

On Sunday, 4 September, they were forced to find shelter near modern-day Port Macquarie. But their Hope was now becoming a reality, and salvation beckoned. Two nights later, they slept onshore for the first time, having passed Port Hunter at modern-day Newcastle.

The distance to Port Jackson was little more than eighty kilometres.

The next morning, 7 September 1803, they filled their water cask again and baked some cakes in their fire before setting off for Sydney. That night the wind died away but the men took to the oars with increased vigour, knowing the finish line was close and the lives of eighty men depended on them.

They sighted the north head of Broken Bay the next morning, and at noon on Thursday, 8 September, a welcoming sea breeze set in. Matthew crowded all sail for Port Jackson and soon after 2pm passed between the heads, with his men cheering the success.

‘Never do I recall,’ Matthew wrote in his journal, ‘experiencing sensations of joy greater than those with which my breast was animated at this time.’

But now he had to organise a return party to the reef – and had no idea what he would find there.

Flinders by Grantlee Kieza will be published by HarperCollins on November 1 and is available to pre-order now.