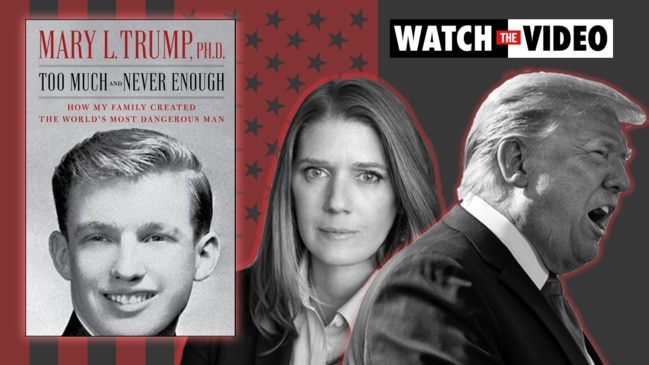

Mary Trump book review: Donald Trump’s father Fred painted as the true villain

The true villain in Mary Trump’s explosive tell-all book about her famous uncle, Donald Trump, is actually not the President himself.

The true villain in Mary Trump’s tell-all book about her famous uncle, Donald Trump, is surprisingly not the US President himself.

Don’t get me wrong – the book is not remotely sympathetic towards Mr Trump. The author makes it abundantly clear that she detests him, and spends the last few chapters on a direct, sustained repudiation of pretty much everything he stands for.

She describes Mr Trump as, among other things, a “pathetic, petty little man” who is “ignorant, incapable, out of his depth and lost in his own delusional spin”.

As a clinical psychologist, with a PhD in Advanced Psychological Studies, Dr Trump also seems to have no qualms at all about casually analysing his personality, in frequently brutal detail.

But ultimately, all the embarrassing anecdotes and explosive behind-the-scenes revelations paint a picture of Donald Trump as a victim – of his childhood, his dysfunctional family, and most of all, his domineering father, Fred Trump.

“In a way, you can’t really blame Donald,” Dr Trump writes.

That line, buried innocuously on page 137, specifically refers to Mr Trump’s reckless spending back when he was a businessman in New York. It could apply to the whole book.

RELATED: Donald Trump’s niece writes tell-all book

RELATED: Explosive revelations in Mary Trump’s book

RELATED: Trump family’s attempt to stop the book

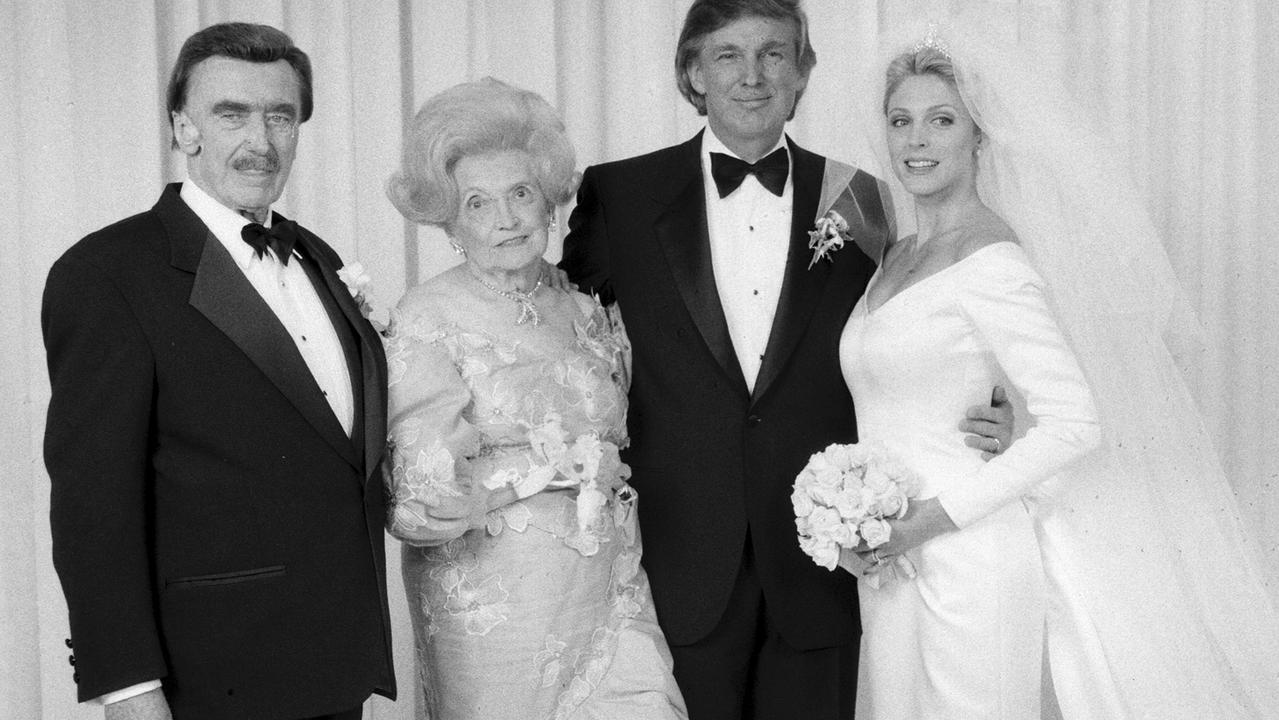

Fred Trump was a wildly successful real estate developer and, according to Dr Trump, a terrible failure as a father.

She diagnoses him as a “high-functioning sociopath” and says he bore “more than a passing psychological resemblance” to murderous dictators like Russian President Vladimir Putin and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un.

Not a nice guy, then.

Dr Trump argues that her grandfather screwed up Donald’s development in a few different ways, the first of which was through sheer parental neglect.

When Donald and his youngest brother Robert were small children, their mother Mary started to suffer from severe health issues, which essentially left Fred as the family’s sole caregiver. He was ill-suited to the task.

“By engaging in behaviours that were biologically designed to trigger soothing, comforting responses from their parents, the little boys instead provoked their father’s anger or indifference when they were most vulnerable,” Dr Trump writes.

“For Donald and Robert, ‘needing’ became equated with humiliation, despair and hopelessness.

“Donald suffered deprivations that would scar him for life.”

That twisted style of parenting would have done enough damage on its own, but even worse, Donald spent his formative years witnessing Fred’s emotionally abusive treatment of his older brother, Freddy Trump – the author’s father. (You will have noted by now that the Trumps are not very creative when they name their kids.)

As Fred’s eldest son, Freddy grew up with the expectation that he would follow his father into the real estate business and eventually take over the family empire. The problem was that he never actually wanted that future for himself.

That lack of ambition, combined with Freddy’s relatively kind personality, sparked a toxic backlash from Fred.

“Fred’s fundamental beliefs about how the world worked – in life, there can only be one winner and everybody else is a loser and kindness is weakness – were clear,” says Dr Trump.

Fred wanted his children to be “tough at all costs”. He believed apologising was a sign of weakness. When Freddy didn’t conform to that world view, Fred responded by belittling him.

“Abuse can be quiet and insidious just as often as, or even more often than, it is loud and violent. As far as I know, my grandfather wasn’t a physically violent man or even a particularly angry one,” Dr Trump says.

“He didn’t have to be; he expected to get what he wanted and almost always did. It wasn’t his inability to fix his son that infuriated him, it was the fact that Freddy simply wasn’t what he wanted him to be.

“Fred dismantled his oldest son by devaluing and degrading every aspect of his personality and his natural abilities until all that was left was self-recrimination and a desperate need to please a man who had no use for him.”

When Freddy briefly tried to pursue a lifelong passion by becoming a commercial airline pilot, Fred viewed it as a “betrayal”. He bombarded his son with abusive messages and derided him as a “bus driver in the sky”.

Freddy eventually died at the age of 42 after struggling for years with debilitating alcoholism, and with his father’s contempt.

Donald witnessed all of this, first as a child and then as the new real estate protege, once Fred decided his eldest was a lost cause.

In Dr Trump’s words, Donald had “plenty of time to learn from watching Fred humiliate” his older brother.

“The only reason Donald escaped the same fate is that his personality served his father’s purpose. That’s what sociopaths do: they co-opt others and use them towards their own ends, ruthlessly and efficiently, with no tolerance for dissent or resistance,” she says.

“Fred destroyed Donald too, but not by snuffing him out as he did Freddy; instead, he short-circuited Donald’s ability to develop and experience the entire spectrum of human emotion.

“By limiting Donald’s access to his own feelings and rendering many of them unacceptable, Fred perverted his son’s perception of the world and damaged his ability to live in it.”

Donald was not at all like Freddy. He was confident; unapologetic; some would say cruel – exactly the sort of “killer” Fred wanted.

Dr Trump spends quite some time explaining how Fred enabled and encouraged Donald’s less edifying habits, like his tireless self-promotion, his tendency to lie and embellish, and his prolific spending on misguided ventures.

To pluck one example from the book’s pages, when one of Donald’s Atlantic City casinos was haemorrhaging money and banks were refusing to lend to him, Fred dispatched his chauffeur with three million dollars in cash to buy up chips, never intending to use them.

No matter how badly he screwed up, Donald never faced any real consequences – a trend that continued in 2016, when no blunder or scandal could derail his presidential campaign.

“The more money my grandfather threw at Donald, the more confidence Donald had, which led him to pursue bigger and riskier projects, which led to greater failures, forcing Fred to step in with more help,” writes Dr Trump.

“By continuing to enable Donald, my grandfather kept making him worse: more needy for media attention and free money, more self-aggrandising and delusional about his ‘greatness’.”

Fred’s malignant influence on his children is the one consistent, recurring thread throughout the book. It ties everything together.

The Trump patriarch died in 1999, and yet in Dr Trump’s description of the family, his presence looms far larger than Donald’s. The President is portrayed as a sad figure; another victim of the family’s true villain.

I was particularly struck by a quote Fred used, again and again, to downplay concerns about his wife’s poor health.

“Everything’s great. Right, Toots?” he would say whenever the subject came up.

Dr Trump describes this attitude as “toxic positivity”. Fred also used it to shrug off Freddy’s fatal addiction to alcohol, and Donald’s reckless spending.

Acknowledging any of those problems would have risked an admission of weakness, so Fred pretended everything was fine instead.

Donald Trump appears to have learned this attitude from his father. It’s the same one he’s expressed, to the frustration of experts, throughout the coronavirus pandemic.

“We have it totally under control. It’s one person coming in from China, and we have it under control. It’s going to be just fine.”

“We’re going to be, pretty soon, at only five people. And we could be at just one or two people over the next short period of time.”

“It’s going to disappear. One day, it’s like a miracle, it will disappear.”

RELATED: Trump’s changing excuses amid the coronavirus crisis

RELATED: Fauci admits US is ‘just not’ doing well with pandemic

As recently as last week, even as the US kept shattering its own record for new daily infections, Mr Trump insisted the country was “in a good place” and its numbers were only rising so fast because there was so much testing.

Nothing to worry about, folks.

“The country is now suffering from the same toxic positivity that my grandfather deployed specifically to drown out his ailing wife, torment his dying son, and damage past healing the psyche of his favourite child,” Dr Trump writes towards the end of the book.

“Every time you hear Donald talking about how something is the greatest, the best, the biggest, the most tremendous (the implication being that he made them so), you have to remember that the man speaking is still, in essential ways, the same little boy who is desperately worried that he, like his older brother, is inadequate and that he, too, will be destroyed for his inadequacy.

“At a very deep level, his bragging and false bravado are not directed at the audience in front of him but at his audience of one: his long-dead father.”

Fred Trump has been dead for two decades. Mary Trump’s book is the story of how his influence lives on.

Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created the World’s Most Dangerous Man is on sale now. It’s published by Simon & Schuster.