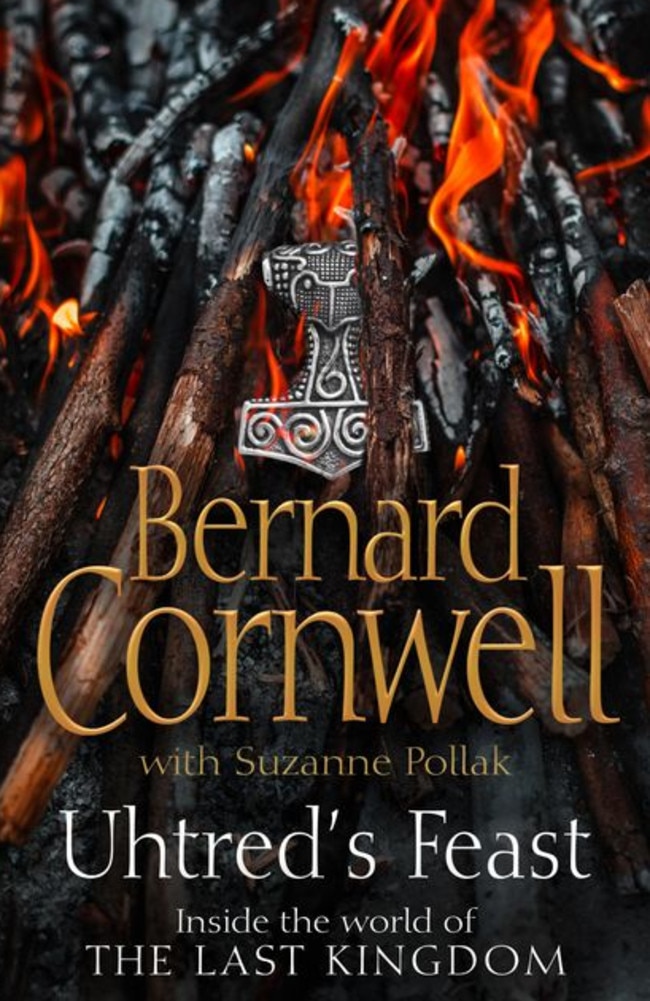

Eat like a warrior boss: Immerse yourself in the world of hit series The Last Kingdom with new book Uhtred’s Feast (plus find out what our hero did next)

Make your meal like a Viking execution and learn which food risks flirting with Satan in kooky companion sequel to The Last Kingdom – plus find out what happened after the hit show ended.

Action-packed Top 10 Netflix hit The Last Kingdom came to an end earlier this year, to the dismay of fans obsessed by the rampaging plot lines and the antics of star Alexander Dreymon’s Saxon warrior hunk, Uhtred of Bebbanburg.

But if you thought you’d said a final goodbye, cheer up: for Uhtred is riding one more time, in a new book by the series’ multimillion-selling creator, Bernard Cornwell, who wrote the novels behind the show.

Uhtred’s Feast is a companion to The Last Kingdom books and show, including new short stories about Uhtred (one reveals what happened after his heart-stopping final battle), plus historical background and dozens of recipes created by food historian and co-author Suzanne Pollak, for those who want to literally gorge themselves on the Viking era.

Today we’ve got a three-course treat for you: some recipes to try – one based on a reputed Viking execution method, another helpfully recommending herbs to avoid accidental flirtations with Satan – plus a chat with US-based Suzanne about how she got involved, and an exclusive extract from one of the short stories in Uhtred’s Feast.

GET YOUR SAXON HACKS ON …

There are scores of recipes in Uhtred’s Feast, many of them vegetarian as that’s what most people of the time would have eaten.

But we’ve pulled out a couple that we reckon Uhtred and his men – plus their terrifying Viking enemies – would rate, along with some appropriate kitchen hacks and tips.

‘BLOOD EAGLE’ SPATCHCOCKED CHICKEN

This playful presentation arises from the ‘blood eagle’ execution famed in Norse sagas. In truth, it is a foolproof method of roasting the perfect chicken; it opens the cavity, which allows for even and immediate heat distribution, whether the chicken is grilled, smoked or barbecued.

– 1 chicken (free-range or organic)

– 1 tablespoon Saxon rub (see below)

– Sea salt

Preheat the oven to 220°C/425°F/gas 7.

First things first, spatchcock the bird! Simply insert your kitchen shears and cut along the backbone, starting up from the tail and going all the way up to the neck. Cut up along one

side, then the other. Reserve this backbone, as it contains all the necessaries for making a simple chicken stock (see page 123 of Uhtred’s Feast). (You can also simply place it below the bird and roast it

before adding to stock.) Crack open or break the breastbone by flattening the chicken down with your hands – apply equal pressure so as not to bruise the flesh. If you prefer, you can ask the butcher to do this for you.

Next, season the bird. Salt it front and back, and all around, then apply your rub, sprinkling it over liberally to provide a good covering.

Place the chicken breast side up in a deep roasting pan, which will do a fantastic job of collecting any rendered fat for you to use in other applications, or to dip the meat into, or baste as it nears completion, if you like.

Place in the oven and roast for 45–50 minutes, or until the bird reaches an internal temperature of 75°C (165°F). You can opt to drop the oven temperature to around 110°C/225°F/ gas ¼ or so after the first 10 minutes, to allow the bird to ‘slow cook’; if you do this, allow 1 hour 30 minutes to 2 hours to cook, depending on the size of your bird.

SAXON RUB

A rub is a combination of spices, peppers and salts that are used for seasoning meats before cooking to enhance flavour and texture. These spices, especially peppercorns, would have

been luxury items, but fennel, coriander, savory and other herbs would have been available to those able to forage and farm. Feel free to try others such as mint, thyme or oregano, but always use them dried. Steer clear of parsley, which the Saxons considered a poisonous flirtation with Satan.

– 1 tablespoon fennel seeds

– 1 tablespoon coriander seeds

– 1 tablespoon white peppercorns

– 1 tablespoon black peppercorns

– 1 tablespoon dried savory

Combine all the ingredients using a pestle and mortar (ideally) or a spice grinder – the mortar and pestle allows one to feel the work and effort needed to transform the spices, connecting one more to the practice. Grind the combined ingredients to your preferred texture – coarse or fine. Store in an airtight container in a cool, dry place. Use whilestill pungent, within six months.

ROYAL BEEF STEW

For most Anglo-Saxons meat was scarce and used mainly as scraps for flavouring dishes. If meat was served, it would have been washed in water then soaked for possibly 12–48 hours, before being boiled in a cauldron over an open fire in the centre of the living space, which was usually a single room. Stewing for a long time made tough meat palatable and retained the nutrients in the cooking liquid.

Today there is no need to wash, soak and boil meat to make a stew, but to impart some Saxon character you can add vinegar, honey, leeks, celery and fennel. You can even add apricots, if you like. A stew this savoury would have required wealth.

Serves 6

– 2 tablespoons butter or chicken, pork or beef fat

– 1.1kg (2½lb) beef chuck or round, cut into 4–5cm

(1½ – 2in) cubes

– 4 large leeks, white part only, roughly chopped

– 350g (12oz) carrots, peeled and cut into chunks

– 1 fennel bulb, trimmed and roughly chopped

– 3 celery stalks, roughly chopped

– 60ml (2½fl oz) vinegar

– 1 heaped tablespoon honey

– 1 bottle of red wine

– 1 heaped teaspoon black peppercorns

– 12 cloves

– Sprig of bay leaves

– 1 teaspoon salt

– A handful of sauteed chanterelles or morels, if available, added before serving

Heat the fat in a casserole pot over high heat and sear the beef pieces. Once browned all over, remove the meat to a platter.

Saute the leeks, carrots, fennel and celery in the same pot until soft, about 10 minutes. Deglaze the pot with the vinegar and add in the honey.

Return the meat to the pot and pour in the wine to cover the meat and add the pepper and cloves. Place the bay sprig on top. Bring the stew to a boil, then immediately turn down the heat to a simmer. Cover and cook on low heat for 4 hours.

Alternatively, cook in an oven set to 120°C/250°F/gas ½ for 4 hours.

Remove the fat, onion and celery, then reheat and taste for salt and pepper. The stew tastes best if it is cooled and keptovernight in the fridge.

Saute the chanterelles or morels, if using, and add to the stewbefore serving with a thick slice of bread that’s been toasted over the fire.

HERE’S TO FEASTING LIKE A HUNK

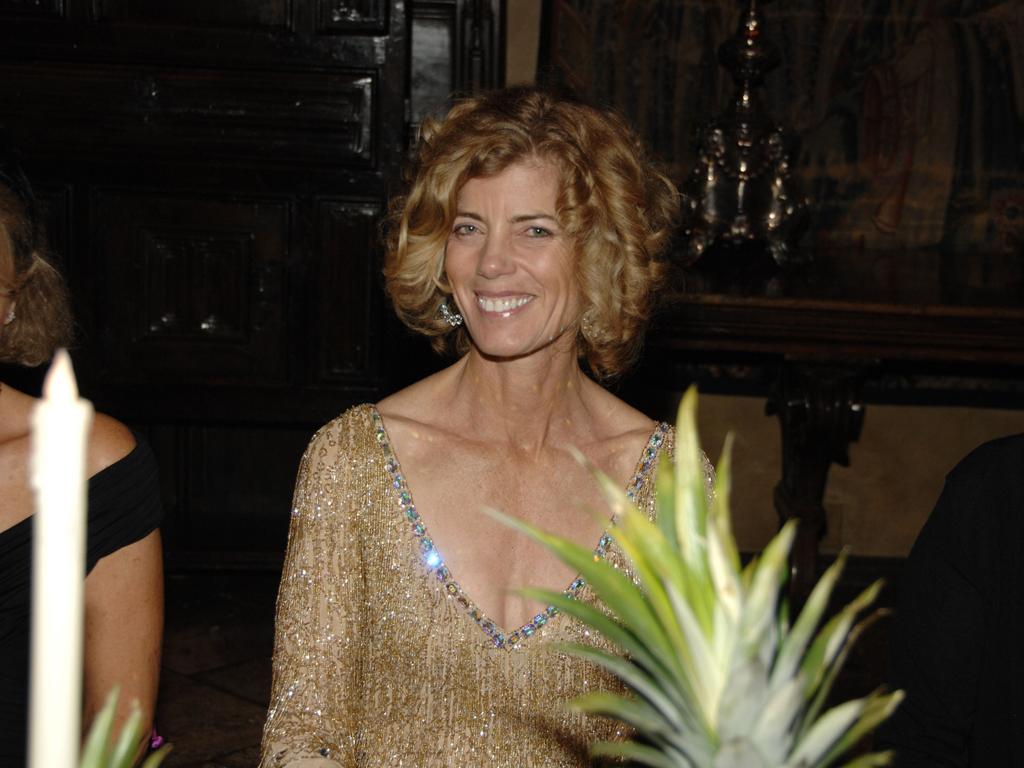

We caught up with Suzanne Pollak, food historian and author, to find out about her role in creating Uhtred’s Feast.

Q: Uhtred’s Feast is a unique publication. How did you get involved?

A: I was hugely lucky to meet Bernard, and his wife, Judy a number of years ago. Bernard knew that I had collaborated with another author, Pat Conroy, on a cookbook. I think he and Judy were trying to be very supportive of me after I divorced. They are angels.

Q: How did you meet Bernard? Are you a fan of his books and/or the televised series of The Last Kingdom?

A: I met Bernard and Judy at a party. I am a huge fan of Bernard’s books, if I had read them when I was a teenager I would know much more about history! One of his books that is very special to me is Sword of Kings because Bernard dedicated it to me.

Q: There are so many recipes in the book. How did you come up with them all?

A: I tried to put my mind on Uhtred: what would this man eat today? I decided on recipe parameters: use ingredients available to the Saxons in ways that the contemporary cook would want to cook; make food reminiscent of that part of the world using Nordic techniques like foraging, curing, preservation.

Q: That must be a lot of work – who was in charge of sampling the dishes? Do you have a personal favourite?

A: Jordan Enzor (a US cookery and gardening expert) was my thought partner and we made many of the recipes together. The book is dedicated to him. I made a strict weekly schedule from January to June, making and testing 100 recipes over that time. My favourite is mushrooms on toast. Of course, I don’t have to forage for mushrooms and risk picking potentially poisonous ones!

Q: Did you learn any unexpected or useful lessons from the process?

A: That there’s a symmetry to Saxon cooking and today’s popular locavore movement. Despite the vast difference in eras, the locavore movement focuses on using what is geographical, just like the Saxons had to do. There is a parallel to cooking with what you have on hand and this ancient cooking where the Saxons used the few ingredients they could find.

Q: You are interested in history, food and an entertaining guru as well as an established author. How did all those come about?

A: My interest in entertaining came about because of my childhood in Africa. My parents gave frequent small and large parties and went to several parties sometimes nightly. The cooking and entertaining books came about totally by accident, including this one with Bernard. I was very lucky to meet the right person at the right time.

Q: Your father was in the CIA. Are you allowed to tell us what he did?

A: My father died when he was 60. In the months before he died he told me a little bit about his job. I can share that he was an undercover agent.

Q: Back to Uhtred. If you were to meet, which of the recipes would you cook to impress him? And which 21st Century food/drink do you think would blow his mind?

A: I would be totally smitten with Uhtred and want to seduce him using food. The salted and smoked pork leg is spectacular and might blow him away. I think Uhtred would be very comfortable hanging out with young chefs and Millennials. Young chefs use the same preservation methods Uhtred’s palate would be familiar with. Millennials believe in zero waste, love meat and fats (keto diet) and will try anything!

EXTRACT: THE GIFT OF GOD

In this exclusive edited extract from Uhtred’s Feast, Uhtred and his warriors accompany the deeply pious King Alfred to meet a Danish chieftain called Hoskuld, who has sworn to make peace and convert to Christianity. But a ghastly discovery awaits.

The monastery had once contained a church, a barn, and other buildings where the monks slept and ate. From our vantage point on the low ridge it seemed as if all those wooden buildings had been set ablaze, all but one, a small house that lay a bowshot to the south. That one house was quite different; to my eyes it looked Roman, with its white walls and tiled roof.

It showed no sign of burning, no smoke came from the shuttered windows or through the

roof and, while my men waited with the king on the low ridge, Finan and I spurred to that one remaining building. I told Alfred we were scouting and that he should wait till we were sure no enemies were in the area.

I had always been fascinated by the buildings the Romans left behind. They were so well made, so impressive and, at the same time, deeply saddening because it was obvious that we could build nothing to compare. The Romans left us soaring temples, massive ramparts and airy, comfortable houses like the one I occupied in Lundene. The roofs actually kept out the rain! This small building was the same and I guessed it had been a farmstead. It had a paved yard at the front where a porch faced towards a small stream, and behind it were three or four rooms.

Finan stepped through the open door first. ‘The monks used the place,’ he said, pointing to a wooden crucifix that had evidently been pulled from a wall of the great room.

‘They’d be stupid not to,’ I said.

‘Probably the abbot lived here,’ Finan suggested, ‘the top dog usually gets the best kennel.’

The enemy had been in, for the furniture had been broken, and against one wall was a massive wooden chest that had been ransacked.

‘They didn’t try to burn the place,’ I said idly.

‘The bastard will want to keep it,’ Finan said. ‘If he rules this territory, he’ll want a home down here.’

The room with the emptied chest had evidently been the abbot’s dining room for it contained a table, six chairs and a hearth that had been crudely hacked through one of the outside walls.

‘No one here.’ Finan had gone into the next room, a small kitchen with another makeshift hearth. Plates, jugs and bowls had all been smashed, to litter the floor with shards.

‘We should get back to the king,’ I said.

‘You go,’ Finan said, ‘I want to scratch around here.’

‘You think they’ll have left you anything?’ I asked, amused.

‘Luck of the Irish,’ he said.

‘I’ll want half.’

‘How lucky are you?’

‘Don’t stay long,’ I admonished him and went back to my horse.

I rode back, swerving close to the burning monastery where the flames were low as they consumed the last timbers.

There was no one in sight, nobody trying to extinguish the fires or even just standing to gawp at the destruction. No enemy either, if indeed it had been an enemy who set the fires, and it seemed most unlikely to me that it could have been an accident. An accident might burn one building, but all of them?

I rode to where Alfred and his men watched from the ridge.

‘You stay here, lord King,’ I called to him.

‘Lord Uhtred …’ he began.

‘They might have left men there,’ I said, though I knew that was not true. I also knew that what he would see would probably drive him into a rage. ‘Cenwulf! Bring all the scouts!’

I turned to Alfred, ‘I’ll send for you, lord.’

He just nodded. He looked so bleak as he gazed at the destruction of his dream, and I felt a stab of pity for him.

‘Let’s go,’ I said to the king’s bodyguard Steapa, and we spurred our horses, drew our swords, and raced towards the embers of Alfred’s hope.

***

They were all dead. The monks, in their dull brown robes, lay about the burning buildings in blood-soaked horror. All of them. We searched to discover one who might yet live, but whoever had attacked the monastery had made certain there were no survivors.

There was the smell of burned flesh, which suggested that many of the monks had been trapped inside or had been tossed into the fires by the enemy, and I had no doubt who that enemy was.

‘Hoskuld,’ I said to Steapa.

Alfred rode through the drifting smoke and, for a moment, I thought he was about to vomit. His anger was evident, a fury that made him speechless for minutes and kept men away from him as he walked his horse among the slain monks.

‘Who did this?’ were his first words addressed to me.

‘I assume Hoskuld,’ I said.

‘You will find the truth of this sacrilege, Lord Uhtred,’ Alfred said sternly, ‘and bring Hoskuld to me at Wintanceaster, where he will die.’

‘Yes, lord,’ I said and just then Finan called from the small Roman building, ‘There’s a live one here!’

‘What did he say?’ Alfred asked.

‘He’s found a survivor,’ I said, and spurred towards the farmstead.

(Apologies for the cliffhanger. You can read what happens next in Uhtred’s Feast)

***

Uhtred’s Feast, by Bernard Cornwell and Suzanne Pollak, is out now, published by HarperCollins.Bernard’s next book Sharpe’s Command is due out later this year.

Drop by the Sunday Book Club group on Facebook and tell us what you think – and whether you’re more keen for the food or the fighting?

Back to modern-day Australia: our new Book of the Month is The Caretaker by Gabriel Bergmoser, which means you get 30 per cent off the RRP at Booktopia by using the code CARETAKER.*

*Ends 31-Aug-2023. Only on ISBN 9781460763131. Not with any other offer.