Charles Bean: If People Really Knew by Ross Coulthart explores work of Australia’s first WWI correspondent

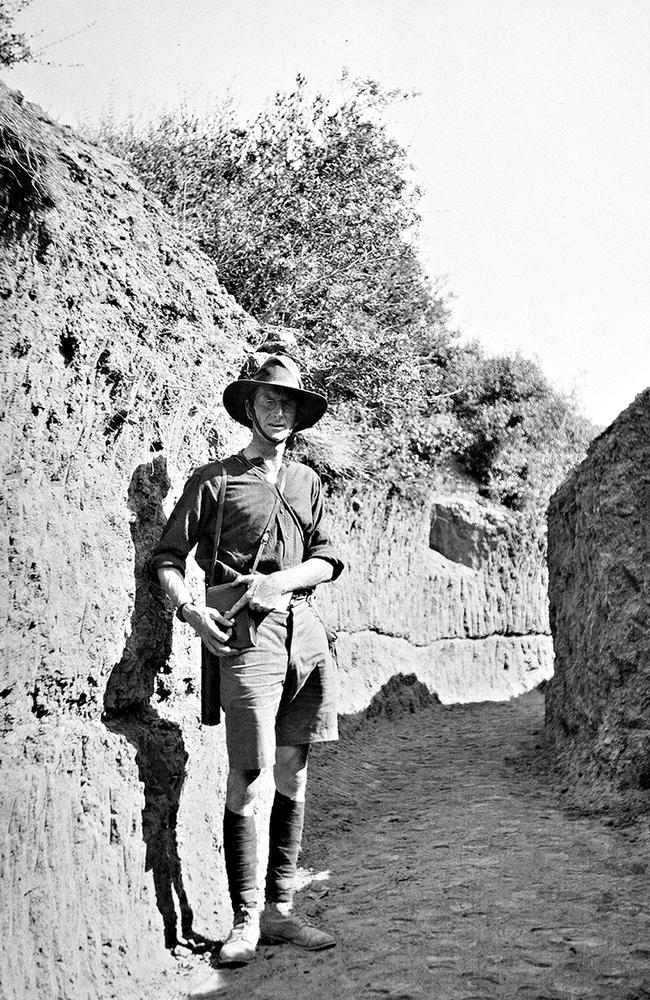

CHARLES Bean was Australia’s first “embedded” journalist in WWI, where he faced monumental frustrations on frontline trenches as he witnessed our troops under fire.

CHARLES Bean was a better historian than he was a journalist.

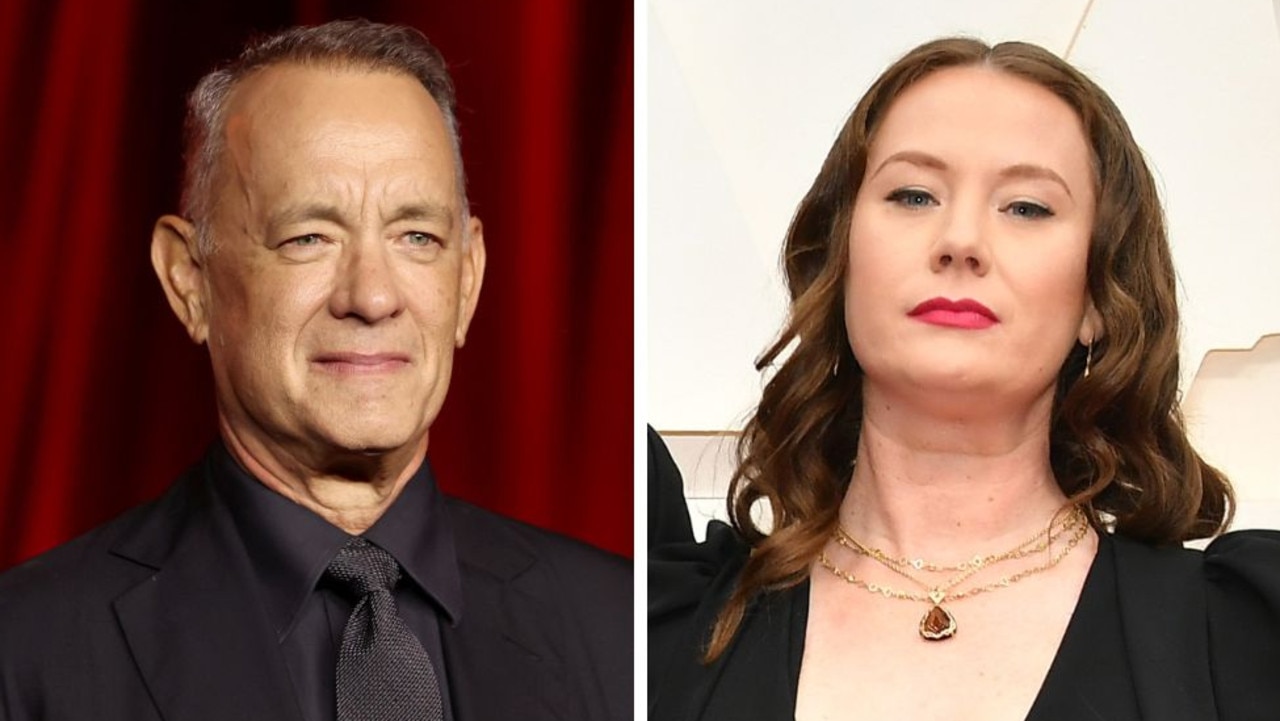

That is the conclusion drawn by author and journalist Ross Coulthart in his exploration of the great dilemma faced by the official First World War correspondent and historian in a new biography entitled “Charles Bean: If People Really Knew”.

Unlike many Great War correspondents Charles Edwin Woodrow Bean dealt with the vexed issue of truth versus national interest by covering Australians at war from every conceivable angle.

For him that often meant briefings with senior generals in the morning followed by a hazardous trek out to frontline trenches to witness and report on troops under fire.

“Bean was unable to peddle the falsehoods and mawkish bunkum spouted by so many other correspondents because, unlike most of his journalistic contemporaries, he was almost always there on the spot to witness the grim reality of the blood and the mud,” Coulthart writes.

“His legacy is an unparalleled historical account of one of the most defining events in Australian history.”

CAMP GALLIPOLI FOUNDER: Australia has lost its identity

FIVE MOMENTS: That committed us to the Great War

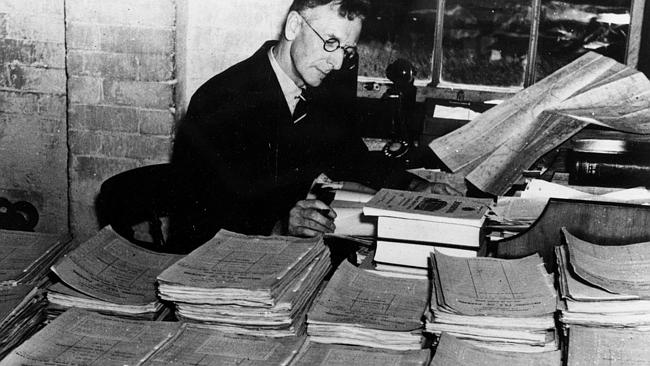

Despite this legacy the author discovered that many of Bean’s dispatches from the front, which were subject to strict military censorship, were at odds with what he had actually witnessed.

Even Bean’s incomparable six volume history of the Great War reflects a more measured view of events than the daily observations recorded so meticulously in his vast collection of diaries. It was in those dog eared, handwritten pages that Coulthart discovered how events written as he saw them differed so widely from many of the official accounts. Without the restrictions of censors or the need to support the war, boost morale on the home front or satisfy jingoistic editors Bean was able to write the truth in these accounts.

Charles Bean was the nation’s first “embedded” journalist and he faced monumental frustrations as he tried to explain in his dispatches a war that on many fronts was being waged by incompetent commanders who wasted thousands of young Australian lives.

“Charles Bean did not want to be a ‘star’ news reporter if that meant compromising the truth,” Coulthart writes.

“There is a lot of evidence in Bean’s favour to show that he did as good a job as he was allowed to do.”

He also did the job with great courage. He was exposed to enemy fire on numerous occasions as he observed the war and at times risked his life to rescue wounded diggers.

The across-the-board access that Bean enjoyed 100 years ago makes modern-day reporters — including Ross Coulthart — green with envy.

He has covered conflicts in East Timor, Iraq and Afghanistan and like all correspondents he has had to deal with military officers that harbour a manic distrust of the news media that often borders on hatred.

“Bean showed that it was possible to fairly and accurately cover a war,’’ Coulthart told News Corp.

“Unfortunately the military today does not give the media a chance. “There should be much more candour about what is going on and it will be interesting to see what happens with the current deployment to Iraq.”

He said he was shocked by the poor coverage of today’s conflicts.

“We can report without jeopardising security.”

For Charles Bean and his ilk there was never any question of compromising security.

Firstly, the battles were long since won or lost by the time their news reports made it to print back in Australia and secondly every word was subjected to the blue pencil of official military censors.

The key issue faced by World War 1 correspondents was accuracy.

Very few followed Bean’s lead and ventured onto the battle field to gather eye witness accounts of the fighting. Many stayed back at headquarters (sometimes in another country) and took as Gospel the often false and nationalistic nonsense fed to them by the high command.

For example the first reports about the ANZAC landings at Gallipoli published in Australia from British reporter Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett were not only way over the top they were grossly inaccurate. Contrary to the truth of the botched operation they portrayed the brave ANZAC’s coasting to an easy victory.

Due to an act of bastardry by British commanders Bean’s more measured and accurate reports (he had actually gone ashore at dawn on April 25) were held back until May 3.

“There is no doubting that Ashmead-Bartlett’s colourful reporting thrilled Australian newspaper bosses and their readers alike but, because he was not on the ground at the time, his story was inaccurate and grossly misleading in its impact,” Coulthart writes.

To his great credit Charles Bean never fell into the trap of embellishing his copy simply in search of a byline or a happy editor.

Coulthart does however accuse him of pulling his punches on Australian commanders in his coverage of military disasters such as Gallipoli, Bullecourt and Fromelles.

“Australian commanders were asleep at the wheel, these debacles were never questioned.

“This was not just censorship, this was self-censorship. He just didn’t want to take them on.”

Despite his criticism of Bean’s work Coulthart remains a big fan of the great chronicler. He said that without Bean’s detailed account of the Battle of Fromelles in the official history the story of Australia’s greatest military tragedy might never have been told.

Bean sheeted home the blame for the loss of 5500 Australian troops in less than 24 hours to General Haigh and his British commanders, but Coulthart argues that in his reports he deliberately softened his criticism of Australian commanders, such as Major General James McCay, who eagerly participated in the doomed Fromelles operation.

The generals’ performance may not have been questioned at the time, but the frank and scathing assessments of subordinate commanders, such as the distinguished warrior Brigadier Pompey Elliott, were eventually published in the official history completed in 1941.

Other scoops, such as the assessment of Beans close friend Major General Brudenell White that Winston Churchill should have been tried for war crimes remained hidden in his diaries. “We know that Winston Churchill is responsible for the deaths of at least 25 per cent of the men who have fallen at Gallipoli — almost as directly responsible as if he had shot them,” White told Bean.

“Well what happens to him — a man like that ought to be hanged as surely as any criminal.”

Coulthart describes Charles Bean as being “starry-eyed” about his friend General White while he treated the brilliant Jewish Victorian citizen soldier General Sir John Monash with utter contempt. Anti-semitism was rife in 1915 and Bean attacked Monash for being a Jew rather than for any flaws in his strategic vision. He mounted a nasty campaign to lobby Billy Hughes in favour of White to become the commander of all Australian forces.

“We do not want Australia represented by men mainly because of their ability, natural and inborn in Jews, to push themselves,’’ Bean wrote of Monash.

He also condemned the Victorian’s supposed “Jewish capacity for worming silently into favour without seeming to take any steps towards it.”

Fortunately sense prevailed and Monash got the nod, was knighted by the King on the battlefield for considerably shortening the war and took his rightful place alongside history’s great military commanders.

Coulthart says it is very sad that many of the stories of poor command could not be written by Bean at the time. Although he saw more combat than probably any other Australian (military or civilian) between 1914 and 1918 he was unable to report many of the disasters that he had witnessed.

“I hope that today if we became aware of similar crises with Australian troops on the battlefield that we would run the story,” Coulthart said.

In addition to his writings Bean’s other great legacy is the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. He had to fight the British establishment and Australian politicians to have the great national museum finally established by an act of Parliament in 1925. After years of design difficulties the building was finally completed in November 1941, two years into the Second World War.

One of the major hurdles was Bean’s insistence that space be provided for the names and details of every soldier killed in the Great War. Those 60,000 names on the bronze roll of honour in the open air cloisters have since been joined by the names of 42,000 more Australians who have died serving their country in conflict.

In typical fashion the modest CEW Bean insisted that his pivotal role in establishing one of the world’s leading war museums should not be mentioned during the opening ceremony.

However Coulthart relates the story of an unknown admirer who could not let the moment pass and he said to Bean, “You must feel proud indeed, this day, to view what you have striven for so long, as an accomplished fact.”

Ross Coulthart records that Bean ended his official history — a labour of love that took up almost a quarter of his life — with an epitaph that is as apt for him as it was for the men whose sacrifice he so passionately sought to commemorate.

“What these men did nothing can alter now. The good and the bad, the greatness and smallness of their story will stand. Whatever of glory it contains nothing now can lessen. It rises, as it will always rise, above the mists of ages, a monument to great-hearted men; and for their nation a possession forever.”

•“Charles Bean: If People Really Knew” is published by Harper Collins. RRP $45.