Book extract: Bob Irwin details his emotional last day with his son, Steve Irwin

BOB Irwin has opened up about the last day he spent with his son Steve before the Crocodile Hunter was tragically killed.

“YOU never expect that’s the last time you’re ever going to see your son, but I certainly had a feeling he sensed something was about to happen.”

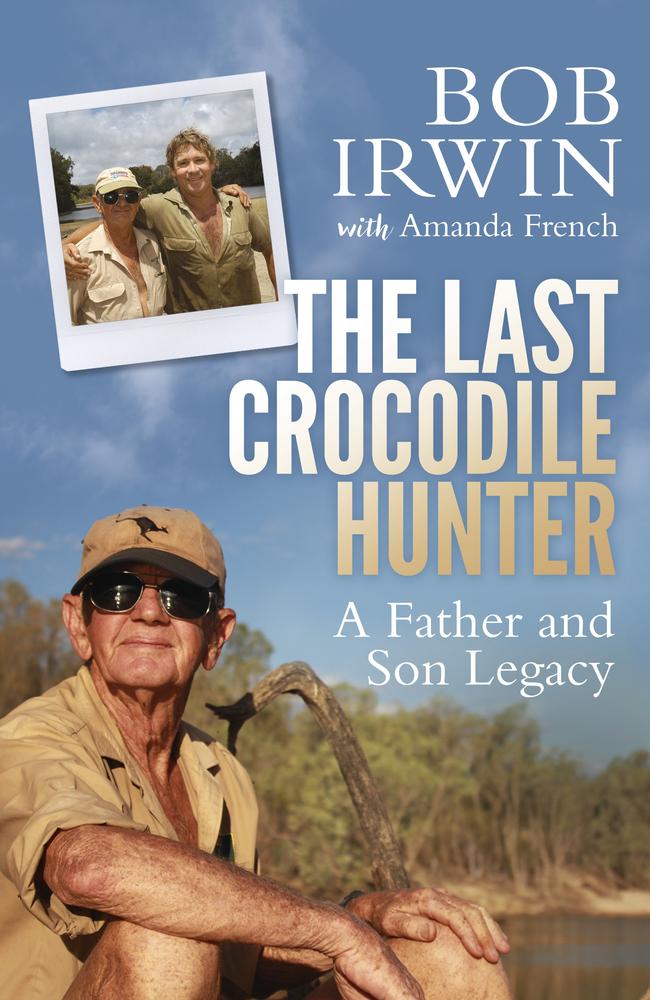

They’re the haunting words written by Steve Irwin’s dad in his new book, The Last Crocodile Hunter: A Father and Son Legacy.

In this exclusive extract, Bob Irwin opens up about the last time he saw his son before the conservationist was killed in September 2006.

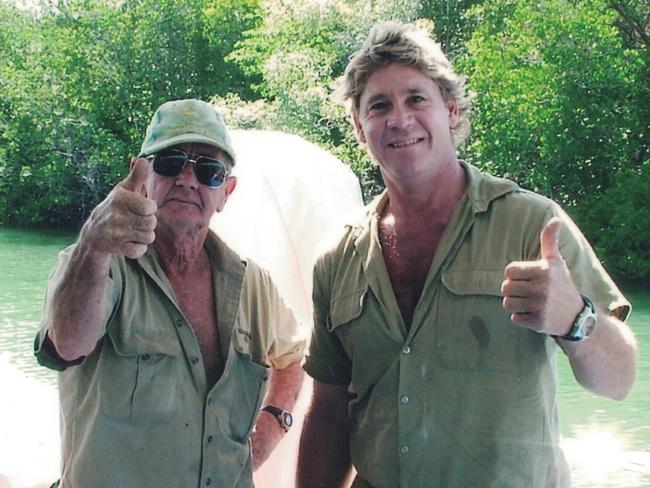

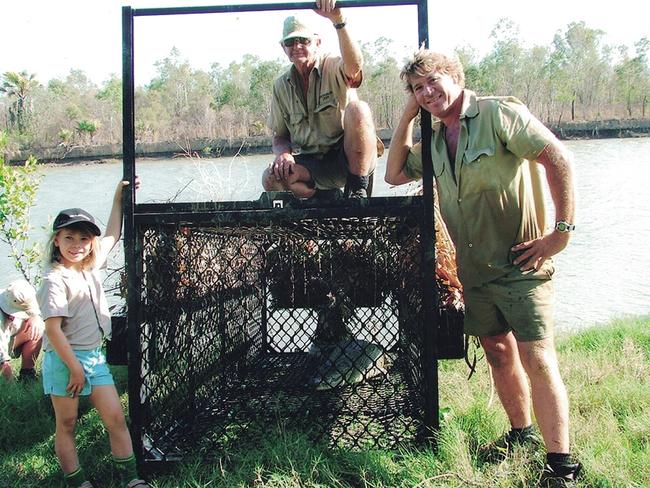

The father and son were wrapping up a month-long crocodile research project in Cape York during which they processed more than 50 crocodiles for the purpose of scientific data.

News.com.au has been given this exclusive extract.

***

STEVE usually went to bed much earlier than me, but on this last night at camp he’d decided to join me around the campfire.

By this time, it was just Steve and me who were up; everyone else from our camp had retired to their tents, exhausted by the events of an action-packed day. Although, he normally slept on Croc One anchored out in the river, Steve had been sleeping in the camp while he’d battled with constant pain from his broken neck and other injuries.

“You know I can see you struggling. It’s as clear as dog’s doovas.”

Steve owned up to it. He knew he didn’t have to keep up his guard with me. “I think I’ve nearly reached my used-by date.”

He was struggling physically because he’d really knocked himself around and he rarely gave himself any reprieve from his injuries.

In his lifetime he’d been snapped, gnawed, clawed, bitten, savaged, jumped on, whacked — you name it. He had scars all over him. No two fingers were the same; each one had either been broken, split or chomped. His hands were virtually scars on scars. In the end you couldn’t tell where one scar started and another finished.

But every single time, he knew that those injuries had been caused by his own blunders.

Growing up, I’d always taught him that if he got bitten, it was through no fault of the animal but his own error. He knew what he was up against every single time. It was all a giant learning curve for him as he kept pushing the envelope with his research and natural curiosity about wildlife. And he was good at that too. Exceptional.

As the two of us took it in turns to stoke the fire from our folding camp chairs, he talked about how badly he’d treated his body and how much this was weighing on his mind with his upcoming filming schedule.

In his life working with wildlife he’d had everything but the kitchen sink thrown at him. Because of this, Steve was constantly working with a lot of pain, and we sat discussing how physically demanding these last four weeks in particular had been on him, and mentally it was challenging him no end.

He acknowledged that he’d knocked himself around badly and had got away with it up to a point when he was young. But it had started to catch up with him.

“I want to cut back on the filming, on all of it. I want to spend more time getting Bindi into it and being home,” he said.

I didn’t get much involved in that side of things; Steve kept me pretty protected from all of that because he knew being in the public eye was never my thing. But Steve told me that he was facing an almost endless series of television projects in the months ahead.

He was due to leave the bush to work on several big television specials and fly to the US to promote his shows. It was an unrelenting schedule which he told me he had little enthusiasm for despite the fact that he was aware of what it enabled him to do for the conservation side of things and spreading his message.

He was physically drained already by the end of this trip, having worked at full capacity over a long time, without a break and in a very unforgiving environment. The mud, mosquitoes and physical endurance of the last month had just about finished him. He wanted more time to get back to the things he really enjoyed, being a dad and being hands-on in the conservation field.

Very quickly the conversation turned to the current trip. We talked about the good times we’d had and appreciated the time we’d spent together as a family.

“We’ve come a long way pretty fast. How good are we?” Steve said.

“I always told you by the time you’d reach 40 you’d have probably grown a brain!” I teased in return. I’d always driven home the fact that that kind of finite direction for a young bloke doesn’t come until much later in life.

We kicked back for hours longer, one of those nights I wished would go on forever. We reminisced over the early days of mishaps, close calls and belly laughter along the track. Modest times when we’d tie our clothes to a rope and leave them out in the turbulent whitecaps of the creek rapids to be washed in our makeshift bush washing machine.

We remembered the animals he grew up with, like Brolly the Brolga who used to steal his marbles and he’d have to wait for them to be digested before he could play with them again.

We laughed out loud remembering the time he released a taipan in my camp — and I couldn’t be sure whether my venomous bed fellow had exited the tent as I crawled into my sleeping bag — and the many times he really tested my patience when he approached me in the zoo as his irritating alias “Glen Glamour” with hideous fake buckteeth and wig to move about unrecognised by fans. Every single time he’d get me with that bloody disguise.

In some ways I might have given Steve experiences and knowledge over the years, but by the same token I got as much back as I gave. It was never just a one-way street.

In these later years, I was learning a lot more from Steve from what he had achieved with the zoo, the team and the research side of things. He’d taken our humble reptile park’s message global.

I probably got a lot more than most parents got out of their children. To have those memories of sharing in really unique experiences to me was pretty special. I can’t think of another dad in the world who might have had an opportunity quite like that.

The hours had really got away from us as the moon shifted across the night sky, and before too long the fire had turned to coal. With a long drive ahead of me in the morning, we decided to call it a night, folding up our camp chairs before I bid goodnight to the green ants one last time and made my way to my tent guided by the light on my head torch.

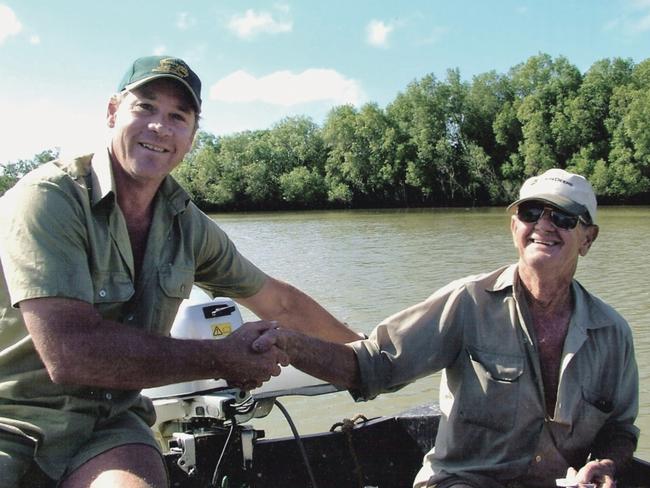

But before we went our separate ways, Steve and I shook hands. It was a routine thing we always did at the end of every day or night.

There was some kind of unspoken acknowledgment whenever we did that. An electricity, as two individuals became physically connected. It was a standard greeting for us, something we did constantly. If a moment was stressful or we’d had a hard time doing something that hadn’t gone to plan or it was a harder day than usual, we’d just shake hands. It was always something I looked forward to.

And each time, without fail, he’d try to break my fingers. He probably could have if he wanted to, because he was gifted with arms like an orang-utan from the day he was born. At the same time he’d give a satisfied smirk while crushing the bones in my fingers with his giant hands. I’d just look at him, not uttering a word.

We’d go through this routine every time. There was no way I would ever give in or let him see my discomfort and yet it hurt like hell. That was always our little thing and something we shared from when he was a really young bloke. He grew to have the strength of 10 men as he wrangled 11-foot crocodiles solo that these days took a team of men to hold down.

As the early morning sun rose over the Kennedy River, the camp inhabitants began to dissipate as the team rose under the shelter of darkness to load their makeshift homes of the past four weeks onto the trucks.

Over the coming days, our exhausted group would look forward to making the long journey home for some well-deserved rest, but it was only the beginning for Steve. As we’d finalised the research project and were able to make a break for home, Steve’s demanding months of filming were just starting. Together with his close friend and manager, John Stainton, his film crew and his lead croc keeper, Briano [Brian Coulter], he was to continue on to the Great Barrier Reef on-board his mother ship Croc One.

I’d packed up the last of my gear, leaving ahead of the rest of the team, doing one final check of the ropes, securing everything on the back of the truck when Steve came over to say goodbye.

He shook my hand. When we made the usual eye contact, I noticed he appeared somewhat emotional.

I realised that the end of his time in the bush was weighing heavily on his mind after the conversation we’d had the night before around the campfire. Being out here always grounded him because it was like his earthwire planting his feet firmly on the soil. The far north was a place he was deeply connected to his whole life. On this particular trip there had been no film schedule, no fans, just the like-minded team of people he’d chosen to surround himself with in the wilds of Australia he so loved.

“See ya later, Bob.”

He always called me Bob; he called me a lot of other things as well, but when we were on our own, he simply called me Bob. I liked that, it made me feel pretty close to him. Because after all of these years I didn’t feel like just his dad, we were more than just father and son. It went way beyond that, a long way.

“See ya, Steve. Take it a bit easier,” I said, fully aware that it was a waste of time saying anything like that, because Steve only had one way of doing things and that was flat out.

I got in the truck, shaking out the pain in my hand from that handshake, well out of Steve’s view, and fired up the engine to traverse the 2000km journey home to Ironbark Station in southeast Queensland.

I drove away feeling a portion of the weight of my son’s pain as I caught him in my rear-view mirror staring blankly at the red tail-lights of my truck. The truck’s lights were my wave goodbye.

To me, he still looked just like that helpless blond-haired kid in an adult’s body, who had a robust, gung-ho exterior but was soft on the inside like the sinking mud of Cape York’s mangroves; that same little boy who, no matter how many times he’d beat himself up, still needed his mum or dad’s reassurance when he was in pain.

As a parent, when your children suffer, you suffer too, no matter how old they grow to be.

I knew that perhaps it was my little secret that he wanted to travel home with everyone else. He was with a group of people he understood, who were dedicated to the vision he had, and he was working with one of the most important creatures to him on the planet.

You never expect that’s the last time you’re ever going to see your son, but I certainly had a feeling he sensed something was about to happen.

This is an extract from The Last Crocodile Hunter: A Father and Son Legacy by Bob Irwin, published on October 25 by Allen and Unwin