The sad tale of Colac’s missing shepherd

A skull found in a remote paddock near Colac was the beginning of the end to one of Victoria’s strangest mysteries.

One of the strangest mysteries in Victorian history was solved when a boy chased a rabbit under a pile of stones.

He was the son of a labourer on a sheep station near Colac and was helping his dad put up a new fence.

When the rabbit darted into a narrow gap beneath the stones, the boy gleefully hauled them off, one by one.

That’s when he found it.

One of the stones, it appeared, was lighter and smoother than the others.

It was a skull, which the excited boy held up to show his father.

When the rest of the pile was cleared away, there was a skeleton, complete with a pair of laced-up boots, that had been rotting in this spot for more than a decade.

An investigation would later find it was the body of Thomas Brookhouse, a shepherd who vanished from the area 16 years earlier.

His head had been bashed in.

It was confirmation of something that had been whispered around these parts ever since Brookhouse vanished: it was murder.

THE MISSING SHEEP

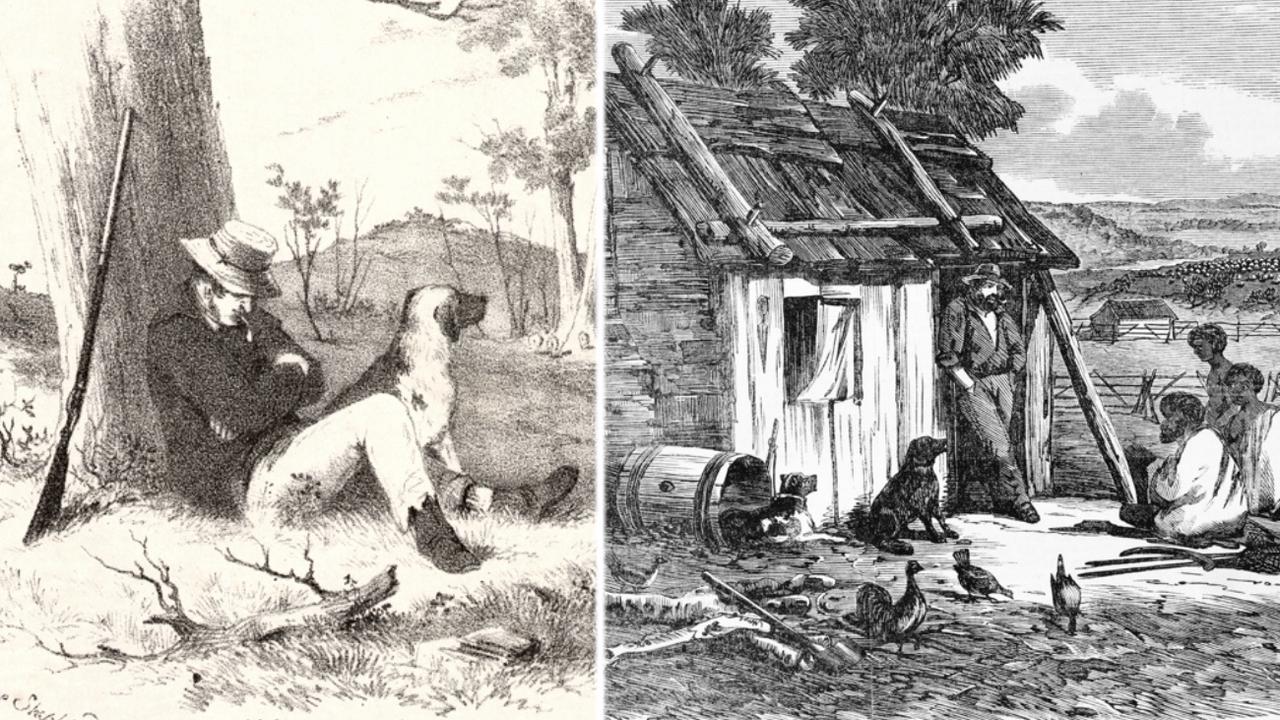

Thomas Brookhouse lived alone in a modest shepherd’s hut, way up in the countryside of the Ti Tree sheep station near Colac.

The station, run by the pioneering Murray family, was dotted with such little houses in which the shepherds lived, sometimes with their families and sometimes on their own, hardly ever seeing another human being.

Their cattle dogs and countless sheep were often their only company.

Brookhouse lived like that. He tended loyally to his sheep and led a meek life and his few human companions knew him by his distinctive protruding jaw and wiry frame.

Then one day the sheep started to go missing.

In a single year, hundreds of the flock vanished.

Brookhouse knew somebody was stealing the livestock and suspicion fell on his colleague and nearest neighbour, an Irishman named Patrick Geary who dwelled in a hut about a kilometre and a half away and possessed a hot temper.

Murray, the station owner, suspected it too. He often used a looking glass to watch Geary’s movements, but couldn’t prove he was the thief.

Then, it got stranger. It wasn’t just the sheep that went missing. Brookhouse himself vanished.

Station workers found the table in his hut set for breakfast, as if he’d simply got up and left without taking any of his possessions.

Even his dog was left behind, and was behaving anxiously.

Dozens of men scoured the countryside in search of the shepherd, to no avail.

Rumours swirled that Geary had murdered Brookhouse, or at least driven him away, because he was about to expose him as a sheep stealer.

But the case went unsolved and there was never another sign of Thomas Brookhouse.

Not until, of course, a boy chased a rabbit under a pile of stones, 15 years later.

GLADLY CONDEMNED

Patrick Geary, in the years since the disappearance of his colleague up at Ti Tree Station, had been eaten by guilt and had turned to God.

His behaviour since the disappearance had become erratic enough for his wife to leave him.

He departed the sheep station and wandered to New South Wales where he found some work.

By the time the skeleton was found and the law caught up with him, he was such a devout Roman Catholic that he was eerily undisturbed by his arrest and trial.

The details that emerged in court were horrific.

Indeed, Geary had an altercation with Brookhouse about the sheep that had gone missing from the station.

When it came to a head, Geary lost his temper, overpowered Brookhouse and pressed the poor man into the smouldering fire of Geary’s hearth.

But that didn’t kill him.

When the burnt and dazed Brookhouse stumbled outside, Geary was ready with an axe.

A blow to Brookhouse’s head ended his life.

Geary, amid the lamentations of his wife, had heaved the body onto a horse and took it out to the edge of the station where he buried it under the stones.

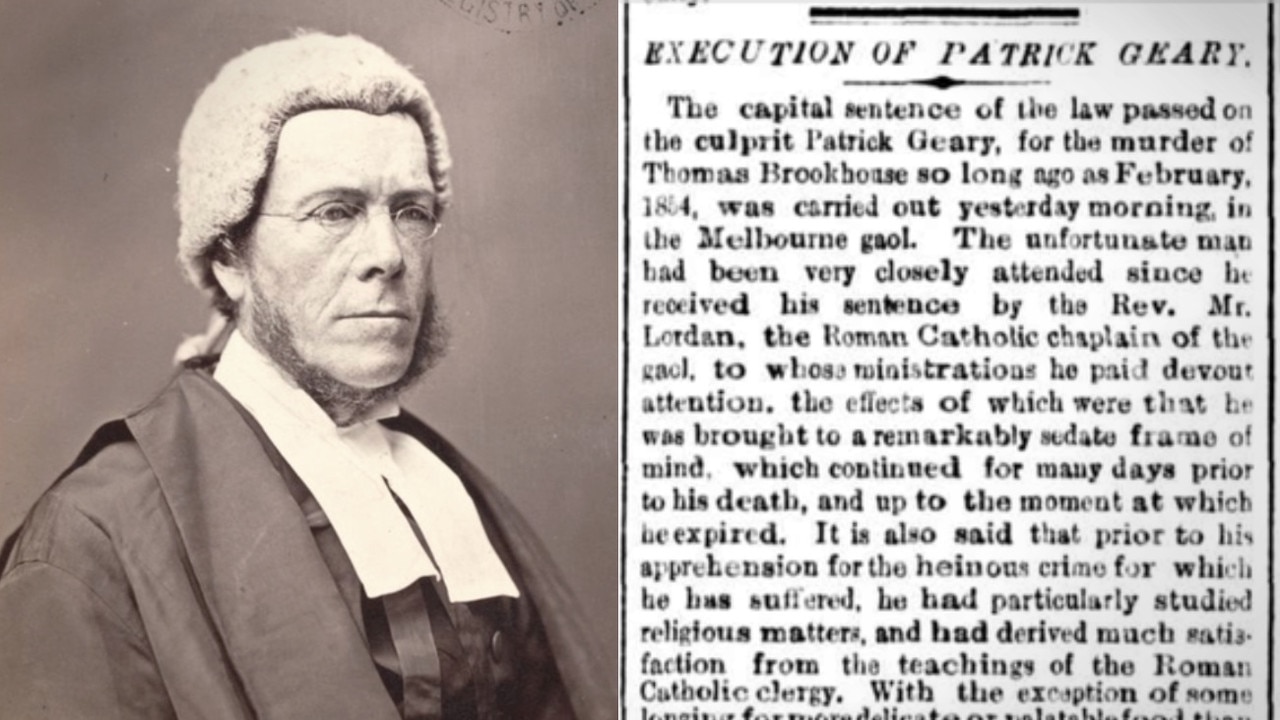

Now in the dock at the courthouse in 1871, Geary seemed strangely pleased when judge Robert Pohlman donned the clack cap and condemned him to death.

Geary exclaimed, “Amen,” and “That is the last of poor Paddy Geary.”

The murderer’s subdued state of religious devotion continued, even as the hour of his execution approached.

Geary was not only at peace with the death sentence, but seemed to be looking forward to it.

After waking in the early morning to undertake his final religious devotion, he faced the noose without flinching and was sent to his sudden death, so too ending one of the strangest murder cases in Victorian history.

Thomas Brookhouse was given a proper burial in Colac, a few days after Geary’s execution.

Lining the streets were old locals who remembered him when he lived and had always suspected foul play.