How we dodged an Australian 9/11 as terrorists plotted New Year’s Eve attack on Sydney Harbour

As families lined Sydney Harbour for the New Year’s Eve fireworks, a mass casualty terror plot was underway. An unprecedented police operation knew of the danger, but not the detail, and cops faced a gut-wrenching dilemma over when to act. LISTEN NOW

Police Tape podcast

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police Tape podcast. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Until 2003, Peter Moroney’s criminal investigative career had been all about breadcrumbs.

It was a breadcrumb trail that the then detective sergeant followed to successfully catch crooks, expose organised crime networks, track money laundering and identify criminal targets.

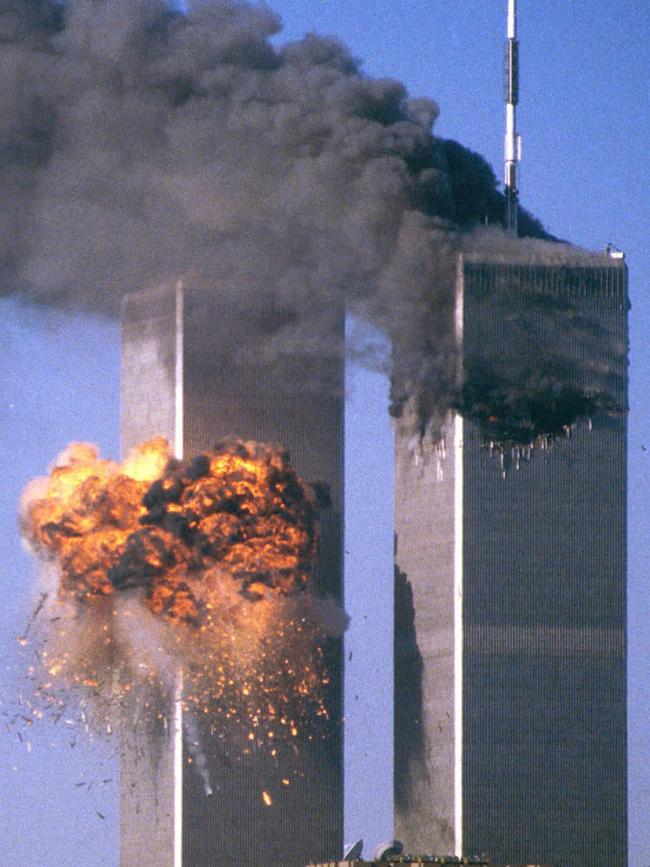

But in that year, NSW Police had a new unit, specifically created in the wake of the four devastating 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States — the Counter Terrorism Co-ordination Command — and what it found changed forever the crime fight in Australia.

A new breed of criminal emerged that to this day continues to evolve, radicalise and threaten the security and safety of all Australians, forcing a law enforcement rethink.

Peter Moroney: Terror threat from hate-filled sleeper cells ‘increasing’

Suburban shooting: How Strathfield massacre gave rise to terror cop’s career

Cracking the code: Sneaky secrets of our old-school crims

The dawning of this new era led to new profiling methods adopted by police forces across Australia, but particularly in NSW and Victoria, which by 2003 already had two dozen terror suspects actively plotting a home soil attack against disbelievers of their faith.

It also sparked what would become the largest, most comprehensive counter-terrorism operation in history, dubbed Pendennis, and redefined how law enforcement hunted terrorists and what they now looked for when a one-size suspect no longer fits all.

“Terrorism investigations in that modern-day form were really new for us, and we were so used to breadcrumb trails being left like a traditional crime,” Moroney told True Crime Australia.

“So if you’re looking at drugs, as an example, you might find someone unemployed in exceptional amount of wealth. You know, thousands of phone calls a day and lots of very quick visits by friends.

“But with the terrorism side of the house, you didn’t see that, you saw effectively for us, here in NSW, all nine (terror suspects) were funded by Centrelink or, for the better part of it, didn’t do much, didn’t go anywhere, went to a prayer hall five times a day and went home or they congregated among themselves. So those telltale signs that we always look for, we thought we should look for, (in) traditional crime wasn’t there.”

MORE FROM POLICE TAPE

Leap of faith: Dicey move as stolen tank threatens city

‘Won’t save lives’: Bitter pill for drug testing advocates

Contract to kill: Gang’s crazy price on two cops’ heads

Shootings: Inside the crime family feud that terrorised a city

‘He choked me’: Hutchence lover’s shocking revelation

Other telltale signs were also missing. There was a lack of use of phones or any other form of electronic communication that could be tapped into or intercepted, and the lack of “human source recruitment” from the Muslim community which made prayer hall infiltration or even just basic surveillance difficult.

HOMEGROWN TERROR THREAT

Moroney said despite the threat detected from extremism in those formative, post 9/11, counter-terrorism years, any attack seemed far off.

“What 2003 onwards taught us was, it was probably one of the first times that it came home to roost that we had technically Australian citizens, albeit some of them born here obviously, or born overseas or Australian residents, that were against us — hated what Australia stood for, hated the involvement Australia had in the then first Iraq conflict. And there was a lot of second guessing … we were starting to see what we would have identified as a lot of covert but overt staking out of key vantage points. There was still a lot of, ‘this is just not happening’ where we were surely misreading the intelligence we’re getting.”

In late 2003, an Islamic community source warned community elders and later police that a local criminal named Mahmoud was espousing hate. He had been on the radar for about 12 months prior because of his extensive criminal background and connections, but things ramped up when he visited a local library and was seen looking up material that turned Moroney’s blood cold.

“When we started to identify some of the behaviour that was occurring and some of the connections and the associations that he was developing, when you took all of that as one big ingredient, that’s when you know — the realisation sets in that this is no longer something that occurs in America,” Moroney recalled. “It was no longer something that could happen on the other side of the world, it was now here.”

COUNTDOWN TO TERROR

On New Year’s Eve 2003, Det Sgt Moroney was monitoring a boat ramp at Hen and Chicken Bay on Sydney Harbour. As children played and families staked out their spot for a fireworks spectacular, a mass casualty terrorism plot was underway.

By this stage, the counter-terrorism Pendennis squad had 12 men on their radar in Sydney and another 17 in Melbourne for what they considered a joint cell posing a multi-plot terror threat. Prime Minister John Howard had been briefed on what Australia was facing and extra resources had been flown in from across Australia.

Two boats had been purchased by the cell as well as other equipment, so it was to be a waterborne attack on New Year’s Eve. As a precaution, an oil tanker that was to enter the harbour that day was ordered to stay out at sea at a cost to the taxpayer of $250,000.

It would be the closest Australia had ever come to a 9/11 level tragedy.

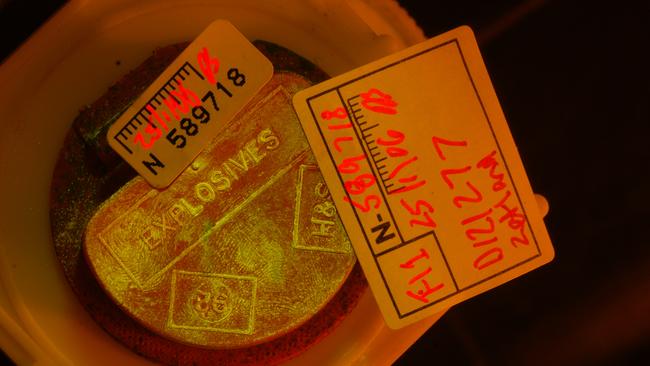

“We were close, days,” said Moroney. “You know, there was so much that we didn’t have, we couldn’t find their chemicals, but we knew they were buying Bunsen burners, chemicals, ice, eskies, all this stuff was there.

“It got to a point where we just said, ‘No more’. We were running 24-hour, seven-day a week surveillance for the better part of three weeks across multiple states. We’d flown in teams from all over the country — irrespective of what organisation you worked for, if you had a surveillance capacity we took it. And we could only run for so long.

“The risk was getting greater, it was coming to a finite point that, if we took too long and we missed it, would have been catastrophic and it just couldn’t happen.”

Police tipped their hand and swooped in on Mahmoud. The attack never took place and what the men had planned was never fully known.

But the cell had been exposed and by 2005 there would be multiple arrests in both Sydney and Melbourne, with all the “pieces of a puzzle” put together from the 16-month investigation to convict the men of multiple plots.

Mahmoud later confessed that one of those had been a planned attack on a naval ship on the harbour that New Year’s Eve.

There have since been two other major terrorist attack plots in Australia. The three-year Operation Appleby targeted 18 Islamic State operatives set to kill nonbelievers; then there was a dual plot to bomb an Etihad flight out of Sydney and attack a train with a gas in 2017. The latter matter is still before the courts.

Originally published as How we dodged an Australian 9/11 as terrorists plotted New Year’s Eve attack on Sydney Harbour