Crims’ money used to help cops with PTSD, with new movie Dark Blue part of $6m campaign

Seized criminal assets are funding a major new initiative to tackle PTSD in police, with a confronting movie spearheading the $6m campaign. It comes as one former cop breaks down in tears telling Police Tape about the cases he’s seen. WATCH AND LISTEN NOW

Police Tape podcast

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police Tape podcast. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Criminals will indirectly fund the police officers they taunt and traumatise, with the proceeds of their crimes to fund a movie, a book and a one-stop help centre to raise awareness of the Post Traumatic Stress Disorder crisis in the ranks of first responders.

The Federal Government has released up to $6 million, largely from seized criminal assets, for various initiatives related to PTSD in police and other emergency workers.

Police Federation of Australia CEO Scott Weber said the irony would not be lost on the thousands of men and women suffering from the trauma they have to deal with every day, from rapes and murders to domestic violence, ice-addled assaults and road accidents.

LISTEN: Former cop Nick Bingham’s cries over the death of Ebony Simpson and tells of his own battle with PTSD

WARNING: DISTRESSING CONTENT

Last year, Beyond Blue highlighted the emergency in the ranks with its “Answering the Call” report drawing on a landmark national survey.

“Across the board it is the major issue, if not the most confronting issue, facing police, and a prime example of that is out of the Beyond Blue report, where it found police officers are three times more likely to have a suicide plan than anyone else in the general population,” Mr Weber said.

“The general nature of policing is becoming more difficult, with the ongoing nature of policing and demands for them to be 24/7 universal problem solvers, to take on more than just policing roles, and the sheer and graphic amount of matters … it’s no longer the traumatic issues, it’s workload, capability of resources and (the) nature of the work is 10 times more difficult.

“From a Police Federation point of view, we are not only trying to reduce stigma, but increase awareness and that’s why we have gone down the path of things like a telemovie which comes out in July.”

Confronting: AFP needs ‘fence at the top of the cliff’ for struggling officers

Graduation Day: I Was Only 19 songwriter’s new song for police with PTSD

A “BlueHub” project will develop a national framework to deal with the crisis, which will include education initiatives, including a booklet, an online awareness campaign and a centre of excellence facility.

The 45-minute Dark Blue drama stars actor and real-life South Australia Police officer Jeff Lang and Emma Beech and will be shown in cinemas nationally for a one-off release and later sold to a TV network. It features Lang as police officer Grant Wood, following him from police graduation through seven years of a confronting career.

Last June a groundbreaking “When Helping Hurts: PTSD in First Responders” report made 31 recommendations on detecting and improving PTSD outcomes for frontline responders.

That project, supported by the AFP, Victoria Police and NT Police and involving independent think tank Australia21 and charity FearLess Outreach, estimated three to four million Australians lived with PTSD or had family affected by it.

Former AFP commissioner and report co-author Mick Palmer said: “First responders run towards danger when others are running from it. We need to make sure we don’t meet the demands of the public and the politicians at the expense of our own people.” He said the chief recommendation to pursue was better training for senior managers to recognise early PTSD signs in their troops to prevent full-blown PTSD.

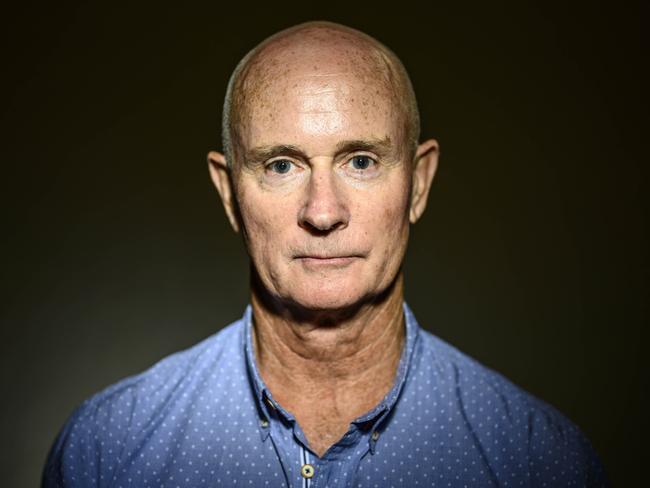

One of NSW’s former top police officers has opened up about the effects of PTSD, describing how one moment he would calmly be watching TV news and the next he would find himself crying.

Nick Bingham said for most of this 30 years as a working police officer he seemed to cope with the horrendous crimes scenes he witnessed and investigated, but then for no apparent reason it hit him.

Who is Nick Bingham?: Drug squad chief’s soft spot for users

“My wife really recognised it before I did, and that was in the last couple of years I was in the police force, and I was becoming quite emotional over things that I recalled or things that I saw on television news,’’ said the former detective superintendent.

In New South Wales, more than 300 officers are medically discharged each year suffering from post traumatic stress disorder which they have acquired while working, with the Police Association of NSW calling it a medical emergency.

“We’re losing 300 highly-trained, skilled police officers from the force every year — you’d think that would be cause for action,’’ said union secretary Pat Gooley.

Mr Bingham said he knew it was time to get out when simple news clips would make him agitated or upset.

“Jobs that I had no part of, when they would come on the news, it would hit a nerve, (I’d) become emotional and, or, bring back a memory … I would tear up,’’ the retired officer told True Crime Australia’s Police Tape podcast.

“You don’t want to be an automaton — you want to have feelings,” he said of going to jobs. “Because if you don’t have feelings, I think there’s something wrong with you really, but you just try and hold it together, and I guess, really, it wasn’t until I was exiting the police — towards ending my career with the police — that these things started affecting me more emotionally than they did at the time.

“There were a lot of jobs that I went to, whether it was a murder or whether it was an accidental death or whether it was a suicide or whether there was a fatal car accident, that you always became emotionally involved in, but you managed to sort of keep it together.’’

Bingham cried as he spoke of the case of Ebony Simpson, a nine-year-old schoolgirl abducted, raped and murdered in 1992, saying he thought of the case most days.

“I think it’s so profound for me because I had a daughter the same age. My daughter was 10, I think, Ebony was nine, but you remember the school photo that everyone gets — the school photo and the school uniform — and a nine and a 10-year-old girl look the same; same age, same ponytail hair, very similar uniform and I see my daughter in that (Ebony’s) photo.”

But he stressed all deaths took their toll.

“There’s no sort of hierarchy of which one is worse than the others. Some of the suicides I went to were particularly unpleasant — where you saw that the person was so desperate they saw no way out and they developed this huge, deep blackness that they just couldn’t get out of, and so their only option in their own mind was to kill themselves.’’

He recalled one incident that stuck in his mind among quite a few he encountered at defence force bases in Sydney.

“I think part of the problem of a young person, and they were all men, young men, living away from home, you know, late teens or early 20s, and not being able to fit in properly. It’s affected them, they become homesick.

“There was this one young fellow, a strapping young bloke, who was about six foot four and good looking, but his colleagues started, for some reason, they thought he was gay. Now I don’t know if he was gay or not, but at the mess where they drank he started getting taunted about it.”

The man killed himself.

“That’s one I remember quite vividly because it just shouldn’t have happened, but it was a part of being taunted, part of being homesick,” Bingham said.

“His dad was in the Army, his grandfather was in the Army and then they, obviously, they were badly affected by it as well.

“So a big part is being affected yourself when you go to the scene of a death — but another big part of it is being affected by the family, being so deeply affected and feeling a bit hopeless that you can’t really do anything for them. You can offer condolences, but really you can’t do anything for them. Nothing will make it better for them.”

• If you or anyone you know needs help, contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Beyond Blue on 1300 224 636

MORE FROM NICK BINGHAM ON POLICE TAPE:

A gang’s shocking contract to kill police; why pill testing won’t save lives — and the moment a police listening device was mistaken for a bomb

WARNING: STRONG LANGUAGE

Originally published as Crims’ money used to help cops with PTSD, with new movie Dark Blue part of $6m campaign