The price for bravado is bullets and blood

The painter and docker tradition of “we catch and kill our own” lives on as underworld wars come and go. Names, decades and ethnic groups change but attitudes don’t.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Live by the gun, die by the gun. This is the code that gangsters like Sam “the Punisher” Abdulrahim and Yusuf Nazlioglu have lived by. And, in the case of Nazlioglu, died for.

The price they pay for bravado is blood. Each of those men was shot in separate incidents in Melbourne and Sydney in the past week, the latest casualties in the new underworld war gripping Australia.

The two had something in common apart from being notorious members of the growing menace loosely labelled “Middle Eastern crime gangs,” and that was this: they knew they had it coming but when it came, they couldn’t show fear.

Amazingly, “The Punisher” survived being hit with multiple bullets sprayed into the front of his luxury Mercedes G-Class 4WD in a funeral procession at Fawkner cemetery last weekend.

Within 24 hours the ornately tattooed kick boxer was photographed in his hospital bed, his chest was lined with bullet wounds that miraculously missed his heart. And he taunted the shooters he knows have been stalking him for months by giving them the finger.

Yusuf Nazlioglu isn’t taunting anyone any more. The former Lone Wolf outlaw bikie died hours after his bleeding body was rushed to hospital from the car park in his apartment building, where he was ambushed by a gunman in Sydney’s western suburbs on Monday evening.

Ever since Nazlioglu was found not guilty in 2020 of killing Comanchero chief Mick Hawi in 2018, he knew there was a ticking clock and a bullet with his name on it.

In fact, plenty of them, a hail of lead sprayed around in much the way that two amateurish gunmen shot down Tarek Zayed and his brother Omar just two weeks before.

Omar Zayed was killed. But Tarek has so far survived despite being critically wounded by a wild burst from an automatic weapon which put one bullet through an eye and smashed his arm so badly it might be amputated.

The Zayed brothers and Hawi were shot outside their favourite gyms, which figures. In their world, regular exercise habits can get you killed.

It’s what happened to prominent ex-bikie and perennial survivor Toby Mitchell, who suffered multiple gunshot wounds from two shooters outside Doherty’s gym in Brunswick in 2011, and other shootings since. Likewise, former Finks strongman Shane Bowden was shot 21 times as he got out of his car late at night after working out at a Gold Coast gym in 2020. Unlike Mitchell, he died.

The “Nike bikie” obsession with pumping iron builds big muscles but isn’t good for their health. Gym sessions put them in the same place day after day. If hit men are tracking you, routine can be deadly as well as dull. And steroids expand biceps but not intelligence.

Both Yusuf Nazlioglu and Sam Abdulrahim shrugged off warnings about threats to their lives. Abdulrahim was so “hot” that several Melbourne kickboxing venues cancelled his “Punisher Promotions” fight nights because police warned of a risk that gunmen would open fire in a crowded venue — in other words, a re-run of the “Ballroom Blitz” at a Gold Coast kickboxing tournament in 2006.

That was the night that bikie turncoat Christopher Wayne Hudson was shot in the face by a former Finks henchman in a terrifying confrontation with the Hells Angels.

Hudson, of course, recovered from his brush with death and went on to commit the atrocious CBD shootings in Melbourne the following year, killing a heroic citizen and badly hurting two others.

If Abdulrahim assumed no one would shoot him at a family funeral at Fawkner last Saturday, he was wrong. A stolen Mazda SUV peeled off from the cortege and raced up beside their target’s black Mercedes “G wagon” — the sort of Hollywood poseur car that appeals to gangsters — so the shooters could spray Abdulrahim with bullets before speeding away, only to crash into a fire hydrant, then hijack another car from a terrified woman at a service station.

Next day, in an unrelated incident, a man admitted himself to hospital in the northern suburbs with a gunshot wound which, of course, he told police was a complete mystery to him. Proof that gunpowder causes temporary amnesia.

In Sydney the next evening it was Yusuf Nazlioglu’s turn but his luck was out. Nazlioglu had always put on a brave front about the likelihood of being a target over his part in the Hawi killing, regardless of his acquittal at trial.

But none of the big talk stopped a hit man lying in wait for him to park his car around 6.30pm.

The attack was shocking but no surprise. While in Silverwater Prison over gun offences in 2020, Nazlioglu boasted of ignoring clear threats while outside jail. In one recorded conversation, he said: “I used to hear people outside were going to knock me, yeah? I used to still leave my house, brother, knowing that one day, someone’s going to sneak up on me and put one in my head.

“But I still f---ing went to the same hairdresser, went to the same f---ing restaurants, yeah. I still showed my face in (the) front yard and hung out with the boys at their porches at their houses, yeah, knowing I’m going to get knocked one day.”

Like the lazy crooks who brazenly use phones to conduct incriminating conversations while half-heartedly warning each other about the risk of telephone intercepts, Nazlioglu ignored the lingering danger until his predicted assassination came true.

Although such suicidal bravado is currently highlighted by Middle Eastern gangsters who seem to be dominating certain outlaw motorcycle gangs, it’s nothing new in the wider criminal world. Neither is the contempt for “snitches” who cooperate with police or other authorities. This goes all the way back through generations of crooks.

One of Victoria’s most notorious killers, Barry Robert Quinn, was doused in woodworking glue and set alight by an even worse offender, his cellmate Alex Tsakmakis, in Pentridge Prison in 1984.

If ever a prisoner did not deserve to be shielded by the code of silence, it was the evil Tsakmakis. But when detectives came to interview the dying Quinn in the Alfred Hospital, he swore at them and turned his face to the wall, refusing to comment.

Perhaps this rebuff prompted one policeman to insert a bogus newspaper death notice for Quinn in the name of “Alex”, an obvious reference to Tsakmakis. It read: “We stuck together to the end.” Cop humour.

When Tsakmakis got his just deserts, it was not from the law. He was killed him by a pillow case with dumbbells in it.

Crime figure Lewis Moran and his younger son Jason shared a brand of fatalism that got them each of them murdered.

Moran the younger knew he was a marked man because Carl Williams had let a contract on him. He left Australia for a few months and could have called on his family and friends to bankroll an extended overseas stay to ensure he was safe.

But for Jason, Europe and America couldn’t match the centre of his world — the postcodes around Flemington and Moonee Ponds. So he came home to where the guns were waiting and was exterminated alongside his friend Pat Barbaro in front of his own small children at a junior football game in Essendon.

Jason’s death, following that of his half brother, Mark Moran, might have made his father Lewis less interested in self-preservation.

Despite a lifetime of rat cunning, the old crook ignored the fact he was a marked man. He insisted on drinking at the same club in Brunswick every day because the beer was not only icy cold but cheap. This made it very easy for the hired killers who stalked him there with his drinking mate, Bert Wrout, in 2004.

Moran’s last words were, “I think we’re off here.” He, too, could have gone interstate and kept his head down until the underworld war ebbed, but (like his dead sons) he was too obstinate for that. He preferred to “die game” rather than hide.

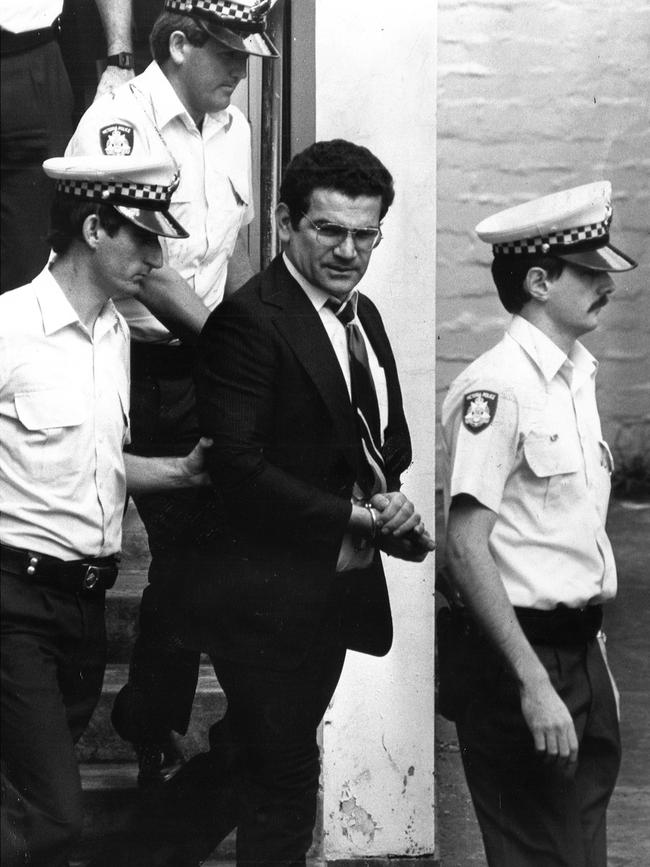

One of Moran’s friends from the 1970s, the standover man Brian Kane, did exactly that. When two armed men in balaclavas burst into the Quarry Hotel in Brunswick in November 1982, Kane knew they were there to kill him the way he himself had killed Ray Chuck, alias Ray Bennett, in the City Court almost exactly three years earlier. That had been a payback and, now, so was this.

Kane couldn’t reach the gun he’d hidden in his woman friend’s handbag, but he instantly pushed her down out of harm’s way then up-ended the table to hamper the shooters. The former Golden Gloves fighter died game, upholding the code that was all he had left.

Those who knew Kane suspected he’d known he was “off” but he stayed around to face the bullets regardless. If he’d survived, he wouldn’t have testified against who pulled the trigger. He was brought up believing the painter and docker tradition of “We catch and kill our own.”

Underworld wars come and go. This latest vendetta has already killed 13 men in Sydney in 18 months and will kill others around Australia before it runs out of players as some end up in the cemetery and others in jail.

Names, decades and ethnic groups change but attitudes don’t.

Perhaps the most notorious of all gangland battles was the St Valentines Day massacre in Chicago in 1929, when seven men were murdered in a garage after being lured there by rival gangsters loyal to Al Capone.

Two of the killers wore bogus police uniforms, and others wore suits, ties and overcoats, like detectives. When genuine police finally got to the blood-soaked garage full of bodies, they found one man still alive but bleeding out from 14 bullet wounds. He was an enforcer named Frank Gusenberg.

Police tried to question the dying gangster but when they asked him who did it, Gusenberg grated: “No one shot me.”

He died three hours later.