‘I hugged the man who killed my husband’: Widow’s astonishing act of restorative forgiveness

The man who murdered Olive Gully’s husband in 2004 could be back on the street soon — and she has extraordinarily chosen to forgive him.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

In a few short months, the convicted killer who made Olive Gully a widow could be back on the street.

But after coming face-to-face with the man who pulled the trigger in her husband’s murder, the McCrae mother says she has made her peace with that.

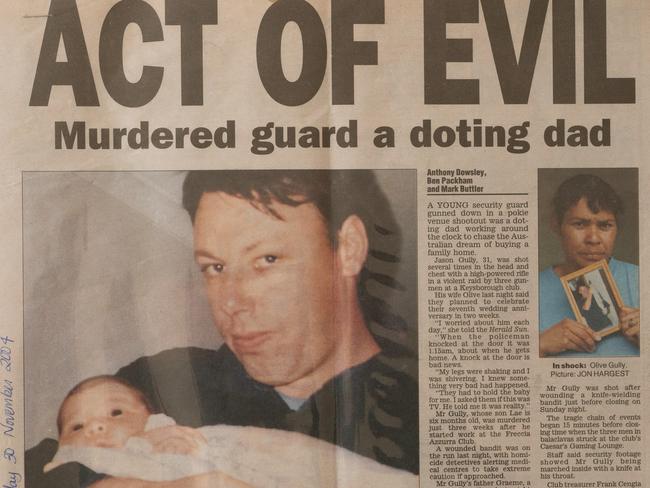

Wally Wariri White, then aged 24, shot 31-year-old Jason Gully, a security guard, in the head and chest while he manned the Freccia Azzurra Club in Keysborough on November 28 2004.

The crime of murder can push many to madness, mission or grief, but Olive stands among only a few who have chosen to forgive the killer who ripped her family apart.

As the 20-year anniversary of Jason’s death approaches, she describes the weight that lifted from her shoulders after meeting the gunman responsible for leaving her to raise a baby boy, Lae, alone.

Through a restorative justice program, Olive and White sat opposite one another behind the walls of the Fulham Correctional Centre, a medium-security prison in Sale, in Victoria’s east, in 2020.

Until that moment, Olive had spent more than a decade languishing over unanswered questions about Jason’s brutal slaying.

“I needed to go there because I didn’t get to hear the end of the story, about Jason’s last days … he had never said anything,” she says.

“That weight, that anger inside about the unknown kind of flowed out of me. I needed to drop it.”

Her heart raced, chills running down her spine as she braced to meet her husband’s killer.

“I felt like I was running out of air. My mind was racing, saying “you will meet him. That door will open and he’s going to come out,” she said.

Then, they cried together.

“He admitted he had done it. It was very emotional and there was a lot of crying. We were in there for four hours,” Olive says.

“We were trying to make peace. I read him a forgiveness letter and we hugged and cried. It was so much to take in.”

With their arms around one another, Olive told White that Lae had been forced to grow up without knowing his father.

“He apologised to me and my son, to his family and to Jason’s family,” she says.

White was sentenced to a minimum of 20 years’ jail for Jason’s murder.

His two accomplices, New Zealand brothers John and Tame Kohunui, are now free after serving at least nine years for manslaughter.

Jason had been employed at the Keysborough venue following another armed robbery on November 2, which the Kohunuis and another man were responsible for.

Soon after Jason’s murder, Olive and Lae relocated to a single storey brick home on the Mornington Peninsula to be closer to Jason’s family, and have remained there ever since.

Aside from the couple’s brief move to the southeast before Jason was killed, McCrae has been Olive’s only home in Australia since arriving from Papua New Guinea.

Olive was born there, and Jason’s family spent several months in the region when the pair were teenagers while his father, a Victoria Police officer, worked as part of an Australian aid program to help train the local force.

Sitting at her dining table holding a framed photograph of her husband, she traces a finger along its gold frame as she recalls the first time they met at age 19.

Jason was in his final year of high school at an international school where Olive worked in the administration office.

“It was funny. When he first asked me to go out with him, I said no,” she says, laughing.

“He asked if we could give it three months, and those three months never ended.”

The couple remained in PNG until they were 23, landing in Brisbane on their way down to Melbourne in July 1996.

They married in a quiet garden ceremony at Jason’s uncle’s home in Frankston the following year.

Lae was born just six months before Jason died.

But more unthinkable tragedy would follow for the newly widowed mother.

Soon after Jason’s murder, three of Olive’s brothers died of tuberculosis in just one year back home in PNG.

Then, in 2017, Olive’s mother died.

Her father passed away in 2022, and she was forbidden to return home for his funeral under the harsh lockdown restrictions in place.

But Lae, now 20 years old, has been Olive’s lifeline here, and he shares more in common with his late father than meets the eye.

Olive surprised Jason when Lae was born, naming him after the city in PNG’s Morobe province where the pair met as teenagers, which is also Olive’s home town.

Lae attended Dromana Secondary College, just as his dad had.

Pictures of the Olive and Lae standing arm-in-arm reveal the tall, curly haired man he has grown into.

Lae may not be the spitting image of his fair-haired father, but Olive says they share the same quiet nature.

That is, she says, until you get them talking about the things they love.

Olive says Lae exudes his father’s wide-eyed enthusiasm whenever he launches into passionate explanations about how to play his favourite video games or mixed martial arts.

“Lae’s very much like his dad. He’s very reserved.

“Jason was very quiet, but he loved hunting. He was this all-Australian guy.”

Olive, now 51 years old, says Jason has remained the love of her life, choosing companionship with friends and loved ones over introducing somebody new into the private world she shares with Lae at home.

Reminders of Jason are peppered throughout the house.

Photographs line a large wooden cabinet in the living room, a small table that leads into the kitchen area, and a tall wooden bookcase behind the dining table.

Lae’s vintage gaming and television show collectables overflow from the shelves below a portrait of his father.

Olive kept old Herald Sun newspaper clippings that documented the aftermath of Jason’s death as it unfolded in 2004.

She fans through the articles, which she keeps in an album for whenever Lae becomes curious about his dad, remembering the things she loved most about him.

“He was an old soul, very caring, very respectful to me,” she says.

“He would open the door for me, or lay his jacket for me to sit down – that old fashioned Australian man.”

Scrolling through pictures of her and Lae together on her phone, Olive describes the day White fired his gun as the point that marks two different chapters in her family’s history.

“I’ve lived longer with my son than my husband, but I should have been able to live longer with Jason,” she says.

“I had a good man, a very good man. He was a very handy man. I lost my handyman.”

Olive’s winding path through grief has been a long and unusual one.

She knows not everybody would choose to face their loved one’s killer, but she says she had to.

She even returned for a second, final time in 2022, which she says allowed a new stage of her life to take off.

“I’m sure Jason would have wondered whether that was a good idea, but he would have given me credit for it,” Olive says.

“I’ve made my peace with him (White). I told him to live his life because he has done his time.

“When I closed that chapter, my career just exploded.”

That path has taken her through all the Victorian courts, both as a victim thrust into the system, and now, as a specialist interpreter for those, often defendants, who find themselves there.

Olive travels across the country to sit in court, now able to completely switch off from the memories of sitting through Jason’s murder trial.

“I’ve done a 180 degree shift inside the courthouse and it really blows my mind that I’m sitting next to the bad boys,” she says.

The career-driven Olive plans to visit her family in PNG next month with Lae, to mark the 20-year anniversary of Jason’s death.

“Everything in life is a journey. We are born to experience it,” she says.

“When we are in a dark space, we think we can’t survive, but we can. I’ve done it.”