Finks bikie gang: witness reveals damning details about life inside OMCG

An insider tells all about life inside one of Australia’s most despised bikie gangs.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

For the Finks, crime is often a family affair.

Being a cousin, brother, or nephew is virtually the only way to fast-track a bid for coveted membership, and the right to wear the gang’s colours.

Over two days last month, a witness, whose identity is suppressed, in a trial involving some of the most feared members of Melbourne’s bikie underworld revealed unprecedented details about the inner workings of the Finks.

By cooperating with police, and giving evidence about the gang, the witness broke the most important rule in the bikie world and earned the label of a “dog”.

He revealed precisely how the Fink’s Melbourne worked during a series of violent tit-for-tat attacks between its members and their rivals, the Mongols.

Among those left with lifelong injuries from the attacks are Finks “world president” Sione Hokafonu, who was shot in the ankle in 2019, and Mongol Rocco Curra, who was shot four times in the head and chest that same year.

The witness said family ties to the Finks were the only sure-fire way to bypass the Finks’ typical “nominee” processes.

“There is normally a nominee – a nom process, as they’d call it.”

“(People with family ties to the gang) immediately became a member of the Finks (if a relative is) already a member,” he said.

As soon as newcomers became a “general member”, they are liable to pay $50 in a week in dues, and had to regularly attend the club’s weekly Friday night meetings at its Cranbourne clubhouse.

Despite the carnage they create in the underworld and the massive teams of police charged with monitoring their movements, bikie gangs are surprisingly small, with weekly chapter meetings attracting “roughly 20 people, give or take”.

In its desperate push for more members and more power, the Finks set-up another, smaller chapter near Ravenhall.

The witness said members moved to the Ravenhall chapter largely to avoid trekking across town for regular club meetings.

More recently, the authoritarian nature of Fink life was exposed in the Gippsland town of Bairnsdale.

Members in the area’s Lindenow chapter were forced to pay fees for the right to wear the club’s patch.

The Sunday Herald Sun was told that some chapter members were fined if they did not answer the phone when their Melbourne overlords called.

In his evidence, the witness also hinted at the unusual power dynamics in the top ranks of the gang.

He described the Finks leadership structure, with Hokafonu being “one of the worldwide presidents”.

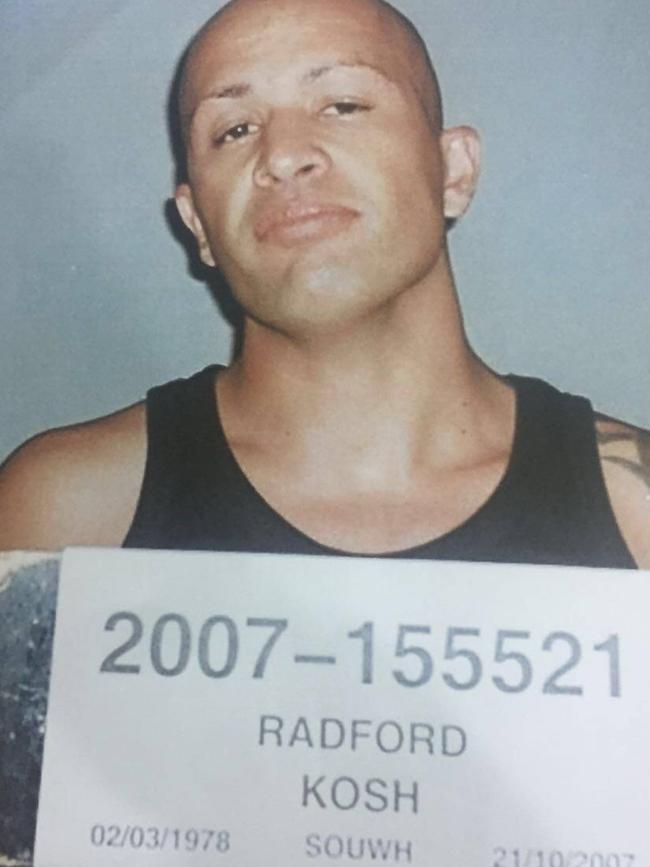

The other man who has been named in that role is the feared Kosh Radford.

It is unclear precisely how Radford and Hokafonu share the gang’s worldwide presidency, but Radford is known to have greater ties to the Finks’ Middle Eastern members, while Hokafonu is better respected among its powerful Pacific Islander contingent.

The most difficult part of gang life is as an unpatched “nom”, with gang rules forcing them to “just have to follow all orders” from members, the witness said.

Failure to do so has “an impact ... down the road whether they might or might not be granted full membership”.

Likewise, members are required to follow orders from the gang’s officeholders.

As often as not, the orders arrive on the encrypted mobile phone app, Signal, which the gang uses to conduct virtually its bloody business.

“The whole club has Signal,” he said.

The use of encrypted communication allowed messages between gang members to be extremely blunt.

The witness described one such message as saying, “Basically ... that the Finks wanted retaliation.”

Unlike other bikie gangs, the witness detailed how women were roped into gang business.

When a woman was involved in a retaliation attempt, the witness said the Finks were desperate to know “more about her” including whether she could be trusted.

Despite reassurances from a gang member, higher-ups in Finks remained wary of the possibility the woman might have been a kind of double agent, loyal to the Mongols.

“They don’t know if it’s a set-up or not,” the witness said.

In a terrifying twist, senior members of the gang kept the member who had vouched for the woman under close watch as “sort of an insurance policy”.

Had the woman turned out to have been aligned to the Mongols, the gang member stood to be hurt — or worse.

“If (he) trusted her, (he) had to be there,” the witness said.

Precisely whether the woman was set to be paid a reward for her efforts, or whether she was stood over by gang members was a hotly disputed issue in court.

But whether she was paid, stood over, or both, the Finks’ willingness to involve outsiders, and women, in their dirty work is almost unheard of in the bikie world.

Gang members were also paranoid about police surveillance, using multiple mobile phones to communicate and conducting their most secretive business away from potential eavesdroppers.

One crucial conversation about a reprisal attack involved gang members meeting at a suburban cafe and leaving their phones behind.

“(They) walked around the block (discussing plans for the attack),” the witness said.

Another meeting was held at an unassuming, largely deserted suburban chicken shop.

On the witness’s account, leaving the Finks did not necessarily involve ritual beatings or the confiscation of prized assets like motorbikes.

To leave, the witness said, it is possible to “just cut contact with everyone”.

The main reason for quitting the outlaw life is simple, he said: “(People) just wanted to straighten out.”