Narcos on the front line: Why Colombia’s murder capital was Medellin

The drug-torn city of Medellin, once ruled by Pablo Escobar, is experiencing a tourism boom, but for many residents the trauma is never far away.

Narcos on the Front Line

Don't miss out on the headlines from Narcos on the Front Line. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The streets of Medellin used to run red with blood.

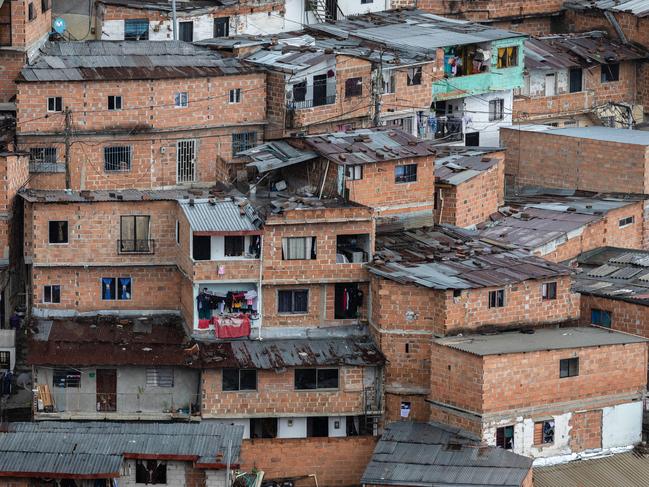

Comuna 13, an illegal, unregulated hillside slum, was once the murder capital of the world.

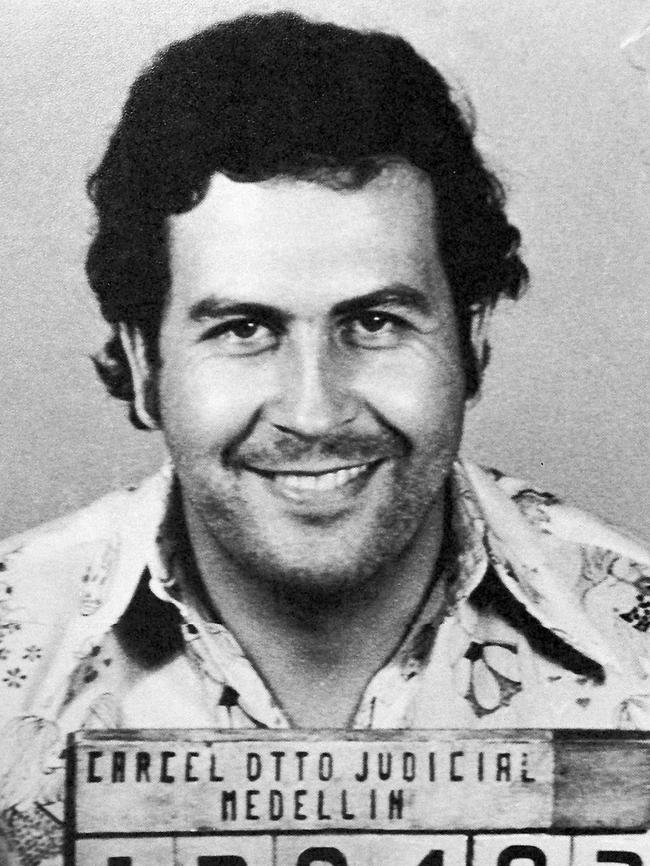

There was no hope in the town when infamous drug lord Pablo Escobar ruled the suburb.

At its height, Escobar’s Medellin cartel was the source of four out of every five grams of cocaine consumed in the United States.

More than $36 billion flowed through the cartel each year.

That power brought jealousies and rivals.

More than 40,000 people were violently killed in Medellin, some by Escobar, and more still by paramilitaries who took over following his death in 1993.

Now the streets are bright; filled with music, dancing, and tourists – something unimaginable in Colombia’s darkest days.

Watch episode 7 of the Narcos on the front line series above.

“It’s progress. Because we are shedding the old stigma of the old Medellin of the drugs and the killings,” Major Luis Guillermo Narvaez Freyre, head of criminal investigations at the Colombian National Police, said.

“And this has also had an influence on our culture and on how people can start seeing the good things, not only the bad things and view Medellin with different eyes.”

Colombia is not a top tourist destination for Australians, partly because of the cost of flights to South America but also because of its reputation.

Most people here only know the mountainous country for the cocaine grown in its hills, and for Escobar’s excesses – helicopters to ferry hamburgers and his own private zoo with hippos that became feral animals – that were glamorised in a Netflix documentary.

But Major General Narvaez Freyre said people were discovering the beauty the nation had to offer while also wanting to find out more about its past.

“We can now see that Medellin is a growing tourist destination,” he said.

“We have some areas that are not so good. By that the improvement has been continuing and we have seen how the tourists are choosing to visit.”

There have been some famous faces on the streets of Comuna 13 since the paramilitaries were booted out in Operation Orionin 2002.

The controversial three-day attack on the paramilitaries, backed by police helicopters, was violent.

But it managed to reduce the murders, and the “disappearances”.

The installation of 384m of escalators in 2011 shortened the walk up the hill from half an hour to five minutes.

The escalators, which were covered by awnings, changed the lives of locals but also enticed western tourists.

Former United States president Bill Clinton has been there 10 times, and many other Americans have gone on a “narco tour”.

Visiting the town was inspiring. People there get on with life despite their poor conditions, and the steep hill that would make most Australians reach for an electric scooter.

But while it’s safer now, and the bars are filled with music and dancing, some remember when the only sounds on the streets was gunfire.

Abel Zapata has lived in Comuna 13 all his life, even having a close shave with Escobar when the crime boss was looking for builders to create his own private prison.

“My boss was one of Pablo’s right hand men, he was someone very important to him,” Zapata said in a translated interview at his home.

“Pablo, when he was building the jail, he gave the order to all his friends to give him a lend of all their workers.

“But I didn’t want to because work for Pablo was dangerous. Pablo could have killed me, I didn’t want to because I have a family.”

Escobar did get his jail built, which was such a palace it became known as “The Cathedral”.

He spared no expense, adding a soccer pitch, spa and waterfall on a hillside in Medellin.

His prison sentence was part of a deal with the Colombian government in 1991.

Escobar agreed to a maximum five-year jail term in exchange for a guarantee that he would not be handed over to United States authorities.

The “king of coke” was unable to last the distance even on such a relatively short stint, going on the run after 13 months.

He was eventually gunned down on a terracotta roof in Medellin by Colombian police, with the backing of America’s Central Intelligence Agency and the Drug Enforcement Administration.

Zapata, 63, said he stood by his decision to reject Escobar’s job, who controlled the area with his signature “plate o plomo”– bullet or bribes – strategy.

It wasn’t safe then, but it was in some small way, predictable.

Two warring paramilitary groups stepped into the power vacuum created by Escobar’s death.

Rosa, a mother of 10 who did not want her surname published, said Medellin changed after Escobar was killed.

She said she remembered the moment when a young local boy warned her that the guerillas were about to execute her son.

“The guy warned me and I went directly to the place where my son was,” she said in a translated interview.

“And I said, “he’s my son, and you got to respect him. If you want to kill him, you have to kill me, too.”

Rosa faced the gunman alone. Her son, one of 10 children, was allowed to live.

Not everyone was as lucky in Comuna 13, with many “disappeared” people suspected of being murdered and buried in unmarked graves on the hills outside Medellin.

Her daughters were also victims of the violence.

“They came into my house, my daughters had to hide under the bed and in the cupboard, they were inside,” she said.

Zapata agreed that the paramilitaries were more dangerous than the drug cartels.

“When Pablo died people didn’t know if that was good or bad because different cartels came to the city,” he said.

“Pablo’s time was really hard but Comuna 13 was worse when guerillas came. You could be dead if you get involved with the cartels.

“But if you get involved with the guerillas or (even if you did) not, you could be dead.”

Rosa has lived in Comuna 13 for almost 50 years.

Her home has two rooms, each about 2.5m long by 2.5m wide. The ground floor included a kitchen, bathroom and bunk bed area on the ground floor.

Four people live in the brick property, which has a prepaid electricity supply.

Rosa was surrounded by her extended family, posing for photographs with her granddaughter Balaria, 6, who was in grade 1 at school.

“When I was growing up the time was really heavy,” she said.

“I don’t want that for my grandchildren, I want something better.”