I hear about it on the news and think, OK, a three-year-old is missing. The lost boy’s face stares out of every news report: William Tyrrell is thin, with cute red cheeks and brown eyes so big and wide you could get lost in them.

He’s wearing a Spider-Man suit and has been caught in the act of roaring, or laughing, at the photographer, who is behind the camera.

The photograph was taken less than an hour before William went missing. Each year, tens of thousands of people are reported as missing to police but most are found, or return home, soon after.

It’s rarer still for a child to still be missing hours later and, even among those, few such cases attract this kind of attention. I don’t know if it is William’s skin colour — he’s white — his age, the vulnerability on that little face in the photo, or the fact his family are from Sydney, where the newspapers and TV companies are based. Maybe it’s all of those things together. Whatever the reason, this is a case where people are sitting up and taking notice.

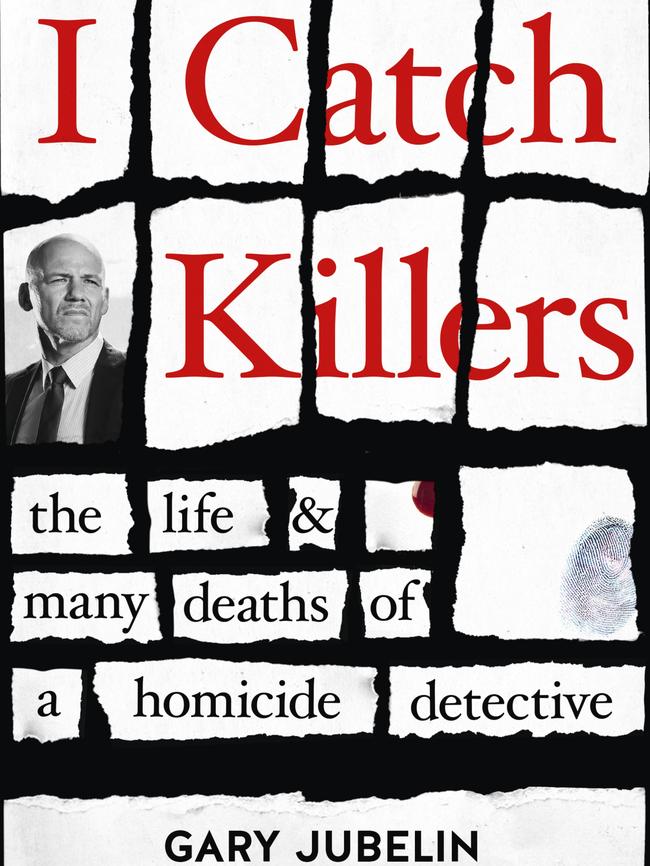

I Catch Killers: The Life and Many Deaths of a Homicide Detective, is published by HarperCollins Australia on Thursday, August 20 in paperback, e-book and audio. Pre-order your signed copy at Booktopia.

The police response appears confused: it’s not clear who’s running the case — the local uniformed commander who’s doing the press conferences, or the Homicide Squad, who are called in after almost a week when it seems likely William hasn’t simply wandered off into the bush, but who never appear on television.

Homicide got the call after my old mentor, Paul Jacob, sent some of his detectives up to Kendall, the tiny town on the Mid North Coast of NSW where William went missing, to help out.

At that time, the cops were treating it as a missing-persons case and a huge search of local bushland had been mounted, but the disappearance of a child inevitably raises fears of something darker and Jaco now works for the Sex Crimes Squad, who specialise in dealing with those kinds of tragedy.

Something about it didn’t feel right, he later tells me. The house where William was last seen is on an isolated road with only a few houses on it. The bush surrounding the property is thick, too thick for a child to wander off into. Jaco says he telephoned the Homicide Squad and told them, “I think you guys should be here.” The cops needed to get on top of this, and quickly, he says. It needed that level of expertise.

Weeks later, Hans, the Homicide cop leading the investigation, walks past my desk in the Homicide office in Parramatta, western Sydney. We chat briefly about the case, and he tells me William Tyrrell is a foster child. The house he disappeared from was his foster grandmother’s, Hans says. And, get this, his biological parents had stolen William before.

They tried to stop him being taken into care by going on the run together and hiding out for a few weeks in a relative’s home, until the police found them. I say it sounds like a good line of inquiry. Statistically, when a child is murdered or goes missing, the perpetrator is usually someone close to them.

Hans walks on, looking confident. An old-school cop and veteran of countless murders, he’s coming to the end of more than 40 years in the police and is now only months away from retirement. The feeling around the office is that this should be a straightforward case for Hans to finish his career on.

***

ALMOST four months later, in early December, William is still missing. Homicide Squad commander Mick Willing calls me into his office. By now, he says, there is no evidence

suggesting either William’s biological parents or his foster parents were involved in his disappearance.

Hans has ruled them out. But there’s little evidence suggesting anyone who could replace them, Mick says. Mick wants me to return from the Unsolved Homicide Unit to the squad proper and take over Hans’s team when he retires in February, which means taking over this case.

Bonus “I Catch Killers” podcast: Gary Jubelin’s most searing interview ever, introducing his explosive new book.

“Jubes, I need you to sort this out,” he tells me. “It’s all over the place.”

Back at my desk, I take a look at the e@gle.i computer system, and can see that Mick is right. It’s obvious how much was missed in those first hours and days when the local cops treated it as a missing-persons case and before Homicide was called in.

Neighbours’ houses were not properly searched, cars came and left the street where William disappeared without being checked, and no crime scene was established.

Even since Hans’s arrival, there is still work that needs to be completed.

The e@gle.i system shows over 1000 items — reports, statements, investigators’ notes — still waiting to be reviewed. Hans prides himself on being a shoe-leather cop, he likes to be out there, on the street, talking to people. As a younger Detective, he spent a lot of time at the Armed HoldUp Squad and still has their heads-down, keep-moving-forward approach, rather than standing back and taking a considered view at what’s in front of him.

Going through the computer files, I can’t even find a written investigation plan. There are only a few cops from Hans’s team working with him on the case. It’s not enough.

Reading through the files, it looks like, for two weeks following

William’s disappearance, the cops still clung to the idea that the three-year-old might have simply got lost, that he was still a missing person, meaning someone whose disappearance has not been classified as something worse.

SEARCHING FOR ANSWERS

HUNDREDS of cops and volunteers scoured 18 square kilometres of bush, farmland and tangled lantana. They searched dams and drains, waterholes and sheds, caravans and cubbies.

Taking this over, it is important to keep my mind open, but even so, it looks almost certain William was not lost. If he were, the massive search effort would have found him.

If not, that means he might have been abducted. That kind of crime is rare, and when it happens, for the family not to be involved is almost unknown. It would be a once-in-a-decade crime within Australia, but it happens.

And if he was abducted, then whoever took him must be someone who was in the area that morning. We need to find out who was there. Most likely, the answer is already somewhere among the hundreds of reports and witness statements on e@gle.i.

The answer is always there, I think. You just have to find it. But the failure to treat this at least as a potential abduction early on has made this work harder. Not least because the hundreds of people who helped with the search, thinking William was lost, were given free access to the road outside the house where he went missing, meaning they would have trampled over any forensic evidence.

Nor do we have complete records of who took part in the search itself, among them SES volunteers, surf lifesavers and even a local pony club on their horses.

This won’t be easy to take over. If Matt Leveson’s unresolved disappearance had called me back into the dark waters of Homicide investigation, this case means taking the plunge

completely. I’m ready to do that now, I think. After 29 years in the cops, I have the right skills, energy and experience. This will need a considered, determined approach. Instead, the confusion continues.

I’m told the strategy agreed on by our bosses is for Homicide to lead the investigation but to co-operate closely with the local cops, who will handle the media.

That way, it’s explained to me, if William was abducted, whoever took him won’t know who’s really coming for them. But this plan isn’t helping.

MEETING WILLIAM’S PARENTS

AHEAD of his retirement, Hans takes me to meet William’s foster parents, Jane Fiore and Tom Nevis (not their real names). On the drive to their home in Sydney’s north, we hear Paul, the local police commander in Kendall talking about William on the radio. He says the case is “actually baffling”.

I turn to Hans. “I thought you were leading this.”

“Whatever that bloke says, it’s got nothing to do with me.” He shrugs.

Hans and I knock on the foster parents’ door and wait. They answer, looking at us in hope, as if we might be bringing them answers, with faces that are drawn and exhausted.

We’re barely inside before Hans says it looks like William’s been taken by a paedophile, and if he has been, statistics show the chances are he’ll have been killed within a day of disappearing.

Jane and Tom are crying.

I can’t let myself feel anything for them, however. Instead, I watch them, thinking: You were both with William that morning. That makes you my first suspects.

Jane pushes some strands of hair behind her ear and looks back at me, as if guessing what I’m thinking. She’s obviously intelligent. She’s had a successful career before becoming a foster parent and there is a stillness to her as if, even in grief, she is still considered. She’s asking Hans about the case; what has been done and what hasn’t.

Despite my suspicions, I get the sense she is genuine in her desperation to find out what

happened to William.

Like Jane, Tom is smart and has been successful, but he seems the more emotional. Watching him, I can see his feelings welling up, his words are catching in his throat, as if they’re threatening to choke him. If he’s play-acting the part of a grieving father, then it’s a good performance.

They tell us how William’s five-year-old sister doesn’t understand what’s happened to her brother. They don’t understand themselves.

On the day before William went missing, they’d made a last-minute decision to head up a day early for a visit to Jane’s mum, Anne (not her real name), in Kendall.

They arrived late and, the next morning, Friday 12 September 2014, Jane and her mother played with the children on the back deck, while Tom went into town to find somewhere with decent reception in order to make a Skype call for work.

William was playing with dice and then, when he got bored with that, he started a new game pretending to be a tiger. Around 10.30am, he jumped down off the deck onto the grass, ran around the side of the house and gave a tiger roar. Then there was silence.

Jane went looking but couldn’t find him. She says she heard a faint, high-pitched scream, as if a child were in pain. It seemed to come from some tall reeds, not far from where she was standing. She ran and looked through them, but there was no sign of William.

“I was saying, ‘William, it’s Mummy … you need to talk to me … it’s Mummy … You need to tell me where you are … You’ve got to say something, William’.”

She called 000 and the cops

came. Soon the street was full of people, searching.

“It’s not a little boy lost,” she says.

William had asthma, which was brought on by stress. He’d not been known to wander off. The bush surrounding the road was so thick the people heading into it were coming out with ripped clothing.

Within moments of losing sight of him, Jane feared he’d been taken.

She’s also sure she saw two cars, one white, one grey, parked on the road outside her mother’s house that morning, before William vanished.

That was strange, because it’s such a quiet place — some distance from Kendall itself, which is only a small town, so small you stay there for any length of time and you’ll recognise most of the people.

“You don’t see strange cars parked on the road,” says Jane. Partly, that’s because all the houses on it are on acre blocks with long driveways, so when people come to visit, they tend to park off the street.

And it’s practically a dead-end road, her mum’s house is the second-to-last one before the bitumen turns into a gravel fire trail leading up into the forest. You wouldn’t be there unless you’re visiting somebody.

Jane says a third car also drove past the house that morning, while she was playing with the children. It was a dark green-grey sedan, she says, heading up the road, towards the fire trail, but then it stopped, turned into the neighbour’s house and reversed out, heading back down the road past them.

The driver stared at her directly.

“The guy held my eyes, he challenged me,”’ says Jane. Then he was gone.

I ask her about William. She describes how he adored his sister. How close he was to his foster dad. How he liked to wait outside the house when Tom was driving home from work to welcome him, so the couple had got into the habit of having Tom send a text just before he arrived, so she could get William ready.

As far as I can see, they are a decent couple, though I am not yet willing to rule them out. Still, when Hans and I leave, I try to reassure them. I don’t want them to fixate on the idea that William was taken. (William’s foster parents have been ruled out by police as suspects in his disappearance.)

Instead, I tell them that we don’t know what happened to him yet, but we won’t give up until we do. We’ll do everything we can to find out where their boy is.

PLEASE DON’T DO THIS

FOR days now, I’ve been telling Hans, “Please don’t do this.” It’s too public. He’s been looking at Bill, a local white goods repairman, who visited Anne Fiore’s house in Kendall a few days before William’s disappearance, to look at her washing machine.

Bill told her he needed to order an extra part and would come back when he’d got it. Hans is interested in this because, five days after William disappeared, a tip-off to Crime Stoppers revealed Bill was the subject of lurid child sex allegations decades ago, although he’d not been charged.

At about 9am on the morning William went missing, his foster mum, Jane, called Bill from her mother’s house, to ask why he hadn’t been back to fix the washing machine. William was last seen an hour and a half after that phone call.

Maybe Bill picked up the message, Hans thinks. Maybe he went back to the house. He can’t have gone inside it, otherwise the family would have seen him, but maybe he was out there, on that isolated road. So Hans wants to search Bill’s home and business.

I say that, if we go in, we need to do so covertly, putting listening devices in place first to listen to Bill and his wife, Margaret’s private conversations.

Going in like this is all or nothing. By now, William’s disappearance is easily the most high-profile criminal investigation in the country. News of the raids will leak.

Sure, get it right and we might find William’s body. But get it wrong, spook Bill before we have any real evidence against him, and we risk losing everything.

But Hans is not persuaded, and he is still running this show. I need to get the search stopped. With Mick Willing on leave, I go to Jason, the acting commander, and, when he won’t call off the raids, ask him to call Mick at home and put the boss on speakerphone.

“Mick, stop this,” I say. I don’t want these raids to happen. I also want to hold a press conference, announcing I am taking over the investigation from Hans. We need to make it clear who’s running this.

Mick does not agree with me. “Gary, Hans is retiring in two weeks’ time,” he says. “He’s been in the job for 40 years, just let him retire in peace.”

“I don’t want this.”

“Mate, it’s not your problem at the moment. You worry about it when you take over.”

***

THE raids on Bill’s home and business go ahead on 20 January 2015. At the time, I’m in Perth with Tracy, trying to keep our marriage going, and also training with David Letizia, the local boxer who has now asked me to work his corner during his final fight, which will take place next month.

Dave’s told me his greatest fear isn’t losing but being embarrassed. I understand it. When you climb through the ropes into the boxing ring, you’re on your own. There’s no one looking after you.

In the world outside that ring, Dave has his family and reputation to fall back on if he needs them, but once he gets inside it he will be exposed.

Which is how I feel, sitting with Tracy, watching reports of the police search on the evening TV news. As I feared, the story leaked. The cameras caught everything. We watch the cops take a cadaver dog inside Bill’s house, trying to smell a body. We watch them rake over the garden. We watch them drain the septic tank.

I try to imagine the effect of these pictures on William’s biological and foster parents but I cannot. It’s too awful.

Afterwards, Bill is put through a six-hour interview, but isn’t charged.

When I get back to Sydney, the word is that they found nothing during the searches, but Bill’s weird. He’s got a strange, nasal voice and a sly way of answering your questions. You can’t form a connection with him.

But he denies having anything to do with William’s disappearance.

One of the Detective sergeants on Hans’s team, Justin, led the interview with Bill. He asked why the call from Jane on that morning doesn’t show up on his phone. Did he delete it?

No, Bill said. He didn’t. Only much later will we learn this may have been because Bill was talking to someone else when Jane phoned him, so her call doesn’t show up in his records.

After a full-scale search and six hours in the interview room with Justin, what have we got to show for it? Nothing. All that’s changed is now Bill knows the cops are watching him.

I tell Tracy I have to sort this out, and shut myself away for two days solid to draw up a proper investigation plan. Tracy is supportive.

WIDENING THE INVESTIGATION

BY now, with all the media attention, everyone in Australia knows who William is, and that we need to find him.

As the cop who’s now facing that task, I need to salvage what I can from this chaos. Given Hans has started working on Bill, I need to see it is done properly rather than drop it.

For one thing, Bill’s alibi has not been checked and we need to do that.

For another, we should search the storage shed he owns in Wellington, a bush town six hours’ drive inland where Bill used to run a business.

We’ve received a report that his car was seen there the day after William disappeared.

We also need to go back to the start of the whole investigation and make sure there have been no missteps, which means ruling the biological and foster parents in or out to my own satisfaction, sorting out the mess on e@gle.i, where sometimes William’s surname isn’t even spelled correctly, and dealing with the media, who are crawling all over this and causing problems — like with the raids on Bill’s house.

At the same time, we need to widen the investigation. We can’t just follow Bill and see where he leads us, we need to also identify and pursue other persons of interest, meaning people who are not suspects but who the police want to talk to, including the large number of known sex offenders living in the area.

How has it come to this? I think, looking at the work in front of me. Why has half of this work, at least, not already been done? A three-year-old has gone missing and we can’t bring our A-game?

I fly back to Sydney, determined to correct that.

SPEDDING IS ARRESTED

ON 23 April, Margaret screams, “No!” as we tell her husband Bill he is under arrest and needs to come with us. Walking with him away from his house back to our unmarked car, I look at the long line of TV trucks and hire cars on the road beyond it and wonder: What the f … has happened?

How do all these journalists, from every major outfit in the country, know that this was happening today? I didn’t tell them. God knows who in the police hierarchy did. I’m furious.

Margaret shouts at the photographers and cameramen crowding closer towards us: “Get off the property! Right now!” They fall back, wide enough only for the car to move forward.

Camera flashes fire at Bill through the windows.

This evening, I guess, Margaret will sit in her empty house and watch her husband’s arrest on the television news. I hope she’s shocked; the charges against him are shocking — the alleged sexual and physical assault of two girls, aged three and six, in the late 1980s — but I did not invent them.

It’s taken months of careful work to get to where we are today. Unlike the first, rushed raids on Bill’s home and business, this moment has been planned for, tested and carefully considered.

I know the damage those television images will wreak in Margaret’s home, as well as in the homes of William’s foster parents and his biological family. That’s why I wanted to avoid them.

But once you take hold of a line of investigation, you have to follow where it leads and, from the moment I took over this investigation, Bill has been the main thread I was given.

THE ONLY CHOICE

THE allegations that form the basis of these sexual assault charges are not connected to William. They come instead from the same Crime Stoppers tip-off that brought Bill into Hans’s reckoning when he was running the case. The allegations date back decades. While Bill was not charged at the time, or after, once we received this report it was our responsibility to follow it up. I’ve spoken to both of the alleged victims.

One of these women’s medical records from the time also suggest an assault took place.

Even then, the decision to act on this evidence was not one I made alone. I spoke to my old team member, Nigel Warren, who worked on the Barbara Saunders and Terry Falconer murders and who now leads a team of his own in the Sex Crimes Squad, asking him to take a look at what we’d gathered.

Nigel’s work now regularly involves prosecuting historical child sex offences and I trust him. He’ll always do the right thing for the right reasons.

He said we had the statements of the alleged victims, one of which seemed to be corroborated by the medical evidence. Nigel had seen cases prosecuted with less, he told me.

I also asked the advice of friends, without naming Bill but saying, “I’m about to pull the trigger on a guy’s life.”

I knew that Bill’s name had already been linked publicly to the investigation into William’s disappearance. Charge him with these crimes and there was no way to hide it. Get it wrong and I destroy him.

At the least, there would be public court hearings in which he would be accused of being a paedophile.

I told my friends we had the evidence of the alleged victims. “What other options have you got?” they asked me.

The police’s own lawyers also looked at the brief of evidence before any final decision was made. Their advice was that there was enough to go ahead. As a cop I can’t ignore that.

As a cop, I wouldn’t be doing my job if I did not also try to take advantage of the extra pressure this will put on Bill by seeing if I can gather evidence to rule him in or out of any role in William’s disappearance.

Bill is silent during the drive to Port Macquarie Police Station. Once we arrive, a custody sergeant reads him his rights, his fingerprints are taken and he is shown into a jail cell ahead of tomorrow’s court hearing.

Anyone would find this frightening. If he is hiding something, maybe this will be enough to crack him open. Maybe it will be enough to make Margaret think about him differently.

COVERT OPERATION

IN the evening, after Bill has been interviewed about the sexual assault allegations, which he denies, I speak to him about William.

He must be feeling that the ground beneath his feet is now much more uncertain and I want him to know that we are waiting, should he stumble.

A thin man, Bill looks back at me coldly. He denies having anything to do with William’s disappearance.

Late into the night, the light from the strike force’s room in the police station shines amid the darkness. Inside that room, I am working, still trying to find a missing three-year-old. Beneath it, in the cells, Bill must know his life has changed for ever.

***

BILL is not our only line of inquiry. So far, we’ve spoken to 18 known sex offenders who live among the acre blocks and rural properties that lie within a 30-kilometre radius of Benaroon Drive, and another 60 who live further beyond it.

There seem to be so many such offenders on this stretch of the Mid North Coast. It’s as if they’ve settled on this quiet, overlooked backwater like mosquitoes.

One of them, Gavin (not his real name), is now Bill’s cellmate at Cessnock Correctional Complex where the white goods repairman is waiting for his next bail hearing. We monitor their interaction.

Both men live near each other in Kendall and both have past links to Wellington, yet it seems they have never met before.

While Bill is in the cell, I go back at him again. We launch a covert operation, the details of which are kept within our strike force and the bosses who authorise it.

It seems to work. Bill continues to insist he was nowhere near Benaroon Drive when William went missing.

That’s it, I think. He didn’t do it. On 8 June, I update the strike force’s investigation plan, to say that, accepting on the balance of probabilities, Bill was not involved in William’s abduction and we need to refocus our investigation.

I know Bill’s reputation and his business have been ruined, the three kids who lived with him and Margaret have been taken away, and Margaret herself has suffered greatly.

I must have made her doubt her husband. But this is a murder investigation. Justice is what matters here, not injury.

I needed to be certain. Yes, getting here was painful, but as the person leading the investigation, I had to weigh up the cost of charging Bill against the cost of doing nothing and found the scales did not balance. The cost of doing nothing was heavier.

All that’s left is for the child sexual assault charges to play out in court.

RIGHT THING TO DO

ON 17 June, Bill’s lawyer tells the Supreme Court he should be released on bail, arguing that someone else, a “known paedophile”, had access to the alleged victims of his assaults at the time they happened.

That paedophile was his then brother-in-law, Jeffrey Hillsley. It’s possible, the lawyer argues, Hillsley committed these offences, not Bill.

After eight weeks in prison, Bill is released on bail. The case moves slowly through the courts and, a year later, he is still fighting it, with no trial scheduled to take place until another year has passed, and which is then delayed again until 2018.

When finally it gets to the NSWs District Court, Bill’s lawyer argues that the allegations against him were made to Crime Stoppers by his ex-wife, following a bitter divorce.

He argues that evidence has been lost and witnesses have died in the decades since the offences were allegedly committed. The presence of Hillsley in Bill’s life at that time also means it cannot be proved who committed the offences, if any did take place.

The judge says he believes no jury could say for certain that Bill’s guilty and, on 5 March 2018, throws out the charges against him. Walking away from the court, I feel a deep sense of sympathy.

Sympathy for the women who were the alleged victims and who told the police about the most awful alleged crimes being committed against them.

Sympathy for Margaret, Bill’s wife, who has been an innocent bystander in all of this. Sympathy for the scrutiny and sheer pressure that we put Bill under.

But it was the right thing to do to charge him. Going to court is usually a bruising experience and not every criminal charge results in a conviction, although it is rare to have your whole case thrown out like this one.

I’d still rather take a case to court and lose than never go to court in the first place.

Jo in Gary and Claire Harvey for an exclusive live event online at 6:30pm AEST on Wednesday, August 19 at True Crime Australia on Facebook.

‘Not good enough’: Top detective’s plea after mum ‘mauled by dogs’

Celebrated homicide detective Gary Jubelin says shocking evidence given at inquest over a mum’s horrific death shows Australia’s cops still have a problem - and families are suffering for it.

Price’s anger at ‘multi-billion dollar Aboriginal industry’

Senator Jacinta Prince has fired up over Australia’s handling of Indigenous affairs, taking aim at the Welcome to Country and men in leadership who have a history of domestic violence. Listen to the podcast.