Tony Mokbel stabbing continued a long line of jailhouse attacks

Tony Mokbel’s brutal stabbing this week was “straight from the prison bashing manual”, one ex-prisoner says. But his attack isn’t the first in a long history of brutal jailhouse blindsides in Victoria.

Prisons are dangerous places full of violent people, a few of them in uniform.

But Raymond Patrick Bennett, alias Ray Chuck, thought he’d be safer behind bars for a while: better to be in the zoo than the jungle when it came to avoiding apex predators.

Bennett had turned an underworld brawl into a blood vendetta by leading his crew of armed painter and dockers to abduct and kill one of the most violent men of their generation, Leslie Herbert Kane.

MOKBEL ATTACK PROMPTS PUSH FOR JAIL SECURITY REVIEW

NEW STABBING DETAILS EMERGE IN MOKBEL CASE

It was a pre-emptive strike. Bennett and his mates traced the lethal Kane to his outer suburban safe house — a unit in Wantirna — early one evening in October 1978 to get in first.

When Kane and his wife and two small children got home from eating at a Chinese restaurant, they were puzzled because their tiny dachshund was not only waiting outside the front door — but was perched on a bench he could not have reached without being lifted. It was a clue but they didn’t take the hint.

THE POWERFUL PRISON GANGS OF MELBOURNE

ANDREW RULE’S LIFE AND CRIMES PODCAST ON ITUNES

Judi Kane knew who the three masked gunmen were as soon as they stepped out but it was too late. They bundled her and the children into a room and killed Kane in his bathroom with silenced guns. His blood was on the floor but his body and his pink Ford Futura car were never found.

That’s why, a year later, Bennett was keen to be in jail instead of being bailed for armed robbery charges against him. Les Kane’s brothers had put a price on his head and Bennett thought he would be safer in custody.

He was wrong.

COURTHOUSE ATTACK

When Bennett appeared in the old Melbourne Magistrates Court that Monday morning in November, 1979, to answer the robbery charges, he would have read a message freshly scrawled in the court holding cell: “Ray Chuck, you will get yours in due course. You f---en dog.”

He was brought through the dock of the main court then sent upstairs to a smaller court, escorted by two detectives. Up there, in a lobby outside the courtroom, sat a man dressed like an anonymous solicitor: blue suit and tie, beard, gold-rimmed spectacles.

Julie Herd, then a court reporter for this newspaper’s predecessor, The Sun, sat next to the “solicitor”. She noticed nothing unusual about him. He sat calmly until the time was ripe.

When Bennett was led past, the “solicitor” jumped up, whipping a handgun from inside his coat. He snarled “Cop this, you mother----er!” and shot Bennett three times.

The detectives jumped back but when one moved towards the gunman he menaced them with the pistol and warned, “Don’t make me do it”.

As the wounded Bennett fled downstairs, carried by adrenaline, a detective chased him thinking the gunman had fired blanks as part of an escape stunt. But Bennett collapsed, saying “I’ve been shot in the heart”. He died on the operating table at St Vincent’s hospital soon afterwards.

The well-dressed killer got away smoothly along a prearranged escape route involving unused back stairs and an exit into the magistrates’ garage, where someone who knew what they were doing had bent up a sheet of corrugated iron, opening a gap into the RMIT car park next door.

Years later, family members confirmed that the hit man was Les’s brother Brian, standover man and former Golden Gloves boxer. Waiting in the car park to take him to the airport to fly to Perth was the third Kane brother — Ray, known as “Muscles”. It was the perfect crime, almost certainly carried out with help from bent police, but it didn’t end well for the surviving Kanes.

Brian’s cards were marked. He was shot dead in the Quarry Hotel in Brunswick three years later. And “Muscles” did a long stretch for killing his “missus”. He wasn’t a loving husband like Ray Bennett, who had tried to buy life insurance not long before his death, inquiring whether the insurer paid out on homicides.

Bennett was always a smart crook — it is widely held he planned the Great Bookie Robbery that had led to the feud with the Kanes, who were keen to take a share of the loot. Not many victims of prison hits had his foresight but it didn’t save him.

HOW JAIL HITS HAPPEN

Most of them don’t see it coming. The classic jailhouse attack is what they call a “sneak go”, and happens as suddenly as summer lightning. The aim is to lull the victim into a false sense of security, which is why so many inside hits are either committed or set up by someone close to the target.

One former prisoner said this week the Tony Mokbel attack seemed straight from the prison bashing manual.

He said Queensberry rules never apply. The aggressors wait for their prey to be relaxed, with their guard down. There was rarely tough talk before a confrontation.

“You want him to think everything’s all right then, ‘BANG’. It just happens.

“It’s a dog-eat-dog world in there. It’s every man for himself. You’ve got to watch your back 24/7.”

The ex-inmate said he had been menaced by one faction to the point where he was helped by a jailhouse powerbroker.

“It got really heavy. I was lucky I had this bloke looking over my shoulder,” he said.

“It helps to be aligned. The scariest were the Islanders, the POW and the Asians. People in here have nothing to lose.”

He said those who attacked Mokbel would have known they would be caught, sent to a management unit like Acacia and prosecuted.

Most prison attacks happen around key times like lockup and musters and are committed in front of others to send a message. Victims usually stay silent.

The only way to eliminate jailhouse violence would be to impose permanent solitary confinement, using remote-control electric doors and video cameras to handle humans as if they were radioactive.

Such hi-tech methods were tried and discarded late last century because they reduced maximum security prisons to inhumane “electronic zoos” that sent people mad. Humans need to be in contact with others. As Mokbel is the latest to discover, that comes with a built-in risk.

THE GANGS MOST FEARED ON THE INSIDE

Like his one-time ally Carl Williams, Mokbel would not want to be seen as dodging potential enemies in the mainstream prison population. Any move to put a high-profile prisoner in protective custody — like “dogs” such as child molesters, sex offenders, informers and former police — would destroy his credibility in the prison hierarchy.

That sort of pride can get you killed. Williams successfully resisted moves to stop him sharing the Acacia Unit with Matthew Johnson, the man who killed him, and Tommy Ivanovic, who was clearly in on the planned execution.

It seems likely Mokbel insisted on “business as usual” after publication of a Sunday Herald Sun exclusive last week revealing he had intervened to help a young prisoner intimidated by a Pacific Islander gang whose members are allowed to think they “run the jail”.

Subscribe to Life and Crimes on iTunes, web or Spotify

Prison gangs are a fact of life, with loyalties divided roughly along “tribal” ethnic lines but also complicated by suburban loyalties and connections with various outlaw motorcycle gangs, among other underworld groups.

A thread of continuity links some of the most notorious jailhouse assaults and murders over many decades.

Johnson, now serving 30 years for killing Williams, spent years as an enforcer for a gang whose members have terrorised fellow prisoners since the mid-1970s. The gang has been known as Prisoners of War in recent years — its members have “POW” tattoos — but its origins are in the feared Overcoat Gang that dominated Pentridge Prison’s H Division from 1975 until the early 1990s, and has some similarity to the notorious Aryan Brotherhood in American prisons.

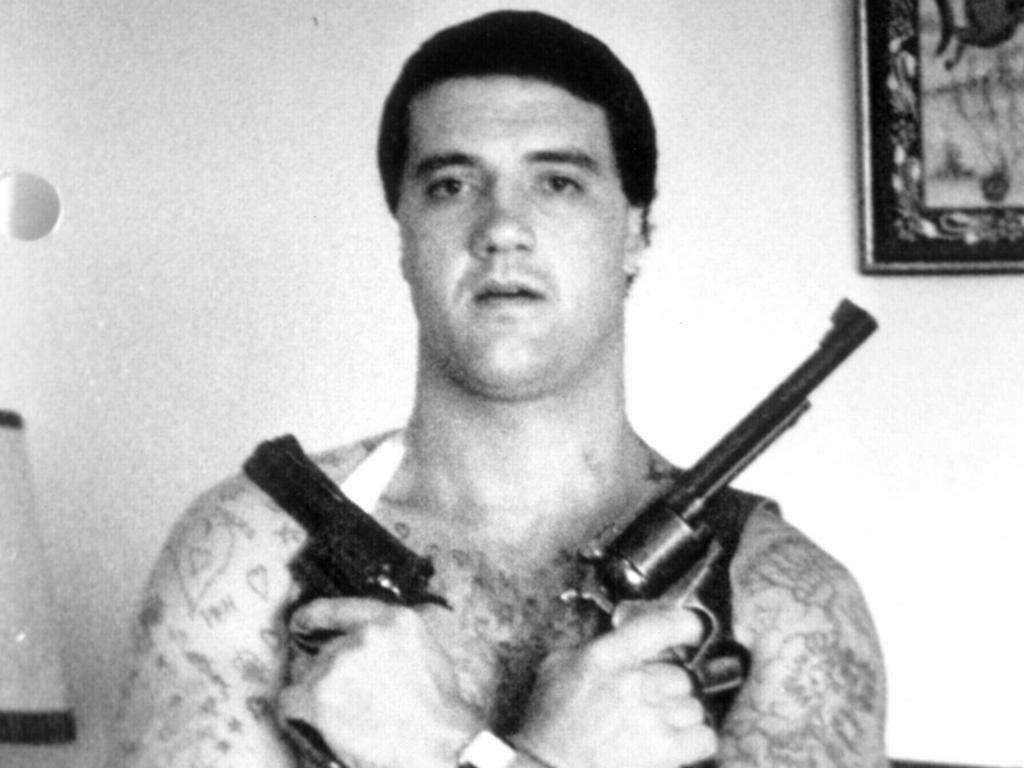

Some members of the first Overcoat Gang died violent deaths — and a few of natural causes since then — but its early members included Mark Brandon “Chopper” Read, indigenous gunman Amos Atkinson, murderer Greg “Bluey” Brazel, robber Gordon “Sammy” Hutchinson and bare knuckle fighter Frankie Waghorn.

When Johnson beat Williams to death — on a Monday afternoon, as with the Mokbel attack — it was a throwback to the activities of the original gang. As a hulking teenager, the young Johnson served time in Pentridge in 1991 and was invited into the Overcoat Gang because of his size, strength and violent tendencies.

“He was a violent young hood. Very young but big, tall, athletic and muscled up,” a former gang member recalled after the Williams murder. Read “handed him the reins” before leaving prison to “retire” to Tasmania.

The Overcoat Gang was so called because its members wore heavy prison-made overcoats — grey with blue patches stitched over the heart front and back so guards on prison towers could “shoot to kill” more easily in a riot or escape attempt. These “targets” aside, the thick coats offered protection from “shivs” and were good for hiding weapons.

The Overcoat Gang began in 1975 after a painter and docker gunman, John Palmer, accused Read of eating extra sausages issued for Christmas lunch. Read denied the accusation and bashed Palmer, starting a vendetta that became known as the “Sausage War”. As the song says, big things from little things grow.

Another gang victim was “Mad Richard” Mladenich, attacked with a spade in a labour yard. Mladenich, who refused to give evidence about the attack, survived but was shot dead in St Kilda on Carl Williams’ orders during the gangland war. It is believed the late Dino Dibra and well-connected gangster Rocco Arico were the last to see Mladenich alive, and that this might have led to the plan to silence Williams.

THE PRISON CODE OF SILENCE

The prison code of silence means jail attacks are often hard to prosecute.

The twisted Barry Robert Quinn, a Charles Manson-like figure, stayed silent despite effectively being burned alive by the evil Alex Tsakmakis in 1984. Quinn had unwisely taunted Tsakmakis about his girlfriend being assaulted and the psychopath got his revenge by spraying him with flammable woodwork glue then flicking lit matches at him.

Quinn was dying from the burns but when detectives tried to interview him in hospital he turned his back. Police did not lose their sense of humour: one inserted a death notice purported to come from Tsakmakis. It reads: “Barry, we always stuck together — Alex.”

Tsakmakis and Quinn were both evil. So there were no tears for Tsakmakis — a suspect for at least six murders, including the Manchester Unity killings of three jewellers — when Russell St bomber Craig “Slim” Minogue killed him with two barbells in a pillow slip in 1988.

It was a cheap shot for Minogue: he effectively got no more time than he was already serving for the bomb outrage that took the life a young policewoman and could have killed many more innocents.

Whether Mokbel can turn his near-death experience to his advantage is yet to be seen. He has the example of Christopher “Badness” Binse, who issued a lawsuit against the State of Victoria after claiming he was stabbed in jail due to official negligence.

Binse, a career armed robber now serving 14 years for a crime spree that ended in a 44-hour armed siege, alleged Corrections staff failed to protect him from twice being attacked in jail in 2006 and 2007.

Binse claimed prison authorities failed to have a system to search for hidden weapons. Whether this would include slicing and dicing of zucchinis or cucumbers in search of “shivs” is hard to say.

The “sneak go” is a jail tradition. Gunman Gavin Preston exchanged hugs and handshakes with five inmates in an exercise yard in Barwon Prison in July 2014 but within moments they stabbed him at a picnic table in the yard attached to the Eucalypt.

The show of friendship abruptly turned to frenzied attack by members of the jailhouse Prisoner of War gang.

After the attack a letter to Matthew Johnson was found in Preston’s cell that indicated there had been an incident between Preston and another POW member.

Preston received nine stab wounds and multiple lacerations to his face and head but still managed to kick one attacker twice in the head. He was serving 11 years with a minimum of nine after pleading guilty to defensive homicide over shooting a drug dealer in the head and to shooting and seriously injuring a second victim in 2012. He is also suspected of shooting former Bandidos bikie enforcer Toby Mitchell outside a Brunswick gym.

Preston stuck with the code after the Barwon attack, refusing to assist police, consent to his injuries being photographed or releasing his medical records. They don’t fight by Queensberry rules, but there is some twisted honour among thieves.

What goes around, comes around in jail. “Little Tommy” Ivanovic, for instance, almost gleefully described Matthew Johnson’s attack on Williams by telephone as he watched. In April 2017, it was his turn to be on the receiving end. He survived an attack in Barwon believed to be revenge for the stabbing of a former ally three years earlier. As with the Mokbel incident, the attacker was a 21-year-old prisoner — leading to suspicions that other prison ringleaders plotted the attack.

Ivanovic was serving a 20-year sentence for murdering motorcyclist Ivan Conabere in a road rage incident in Brunswick West in 2002. He had followed Conabere home, where the murder was recorded on security footage.

When he was jailed in 2003, he had a chance of getting out in 15 years with good behaviour. But trouble seems to have followed him.

MORE FROM TRUE CRIME AUSTRALIA

COLD CASES: