Port Arthur anniversary: Former Tasmanian Premier Tony Rundle recalls what he saw shocked the world

For those caught up in the Port Arthur massacre, time has still not healed the emotional scars of that horrific day. WARNING: GRAPHIC

Crime in Focus

Don't miss out on the headlines from Crime in Focus. Followed categories will be added to My News.

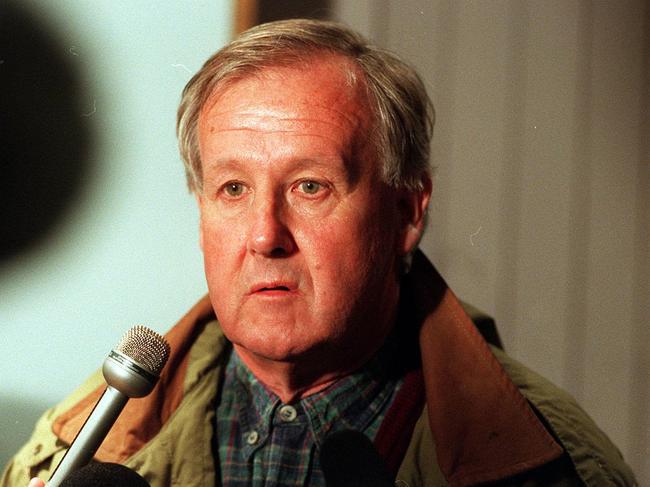

Tony Rundle vividly recalls flying towards Hobart on that autumn day in 1996, a sick sense of foreboding hanging over him.

The then-premier of Tasmania had been preparing to drive from his farm outside Devonport in the state’s north-west to the capital ready for the week’s Parliamentary sitting.

It was Sunday, April 28.

“A phone call came through about 2.30pm from my chief of staff saying there were reports of an incident at Port Arthur,’’ Rundle, now aged 82, told News Corp.

“It appeared that a gunman could be on the loose and there could be casualties and that I should get to Hobart as soon as possible.’’

As Rundle tried to hire a light plane, police in helicopters began arriving at Port Arthur, a former penal colony on the picturesque Tasman Peninsula, a 90-minute drive southeast of Hobart.

What they saw would sicken them and shock the world.

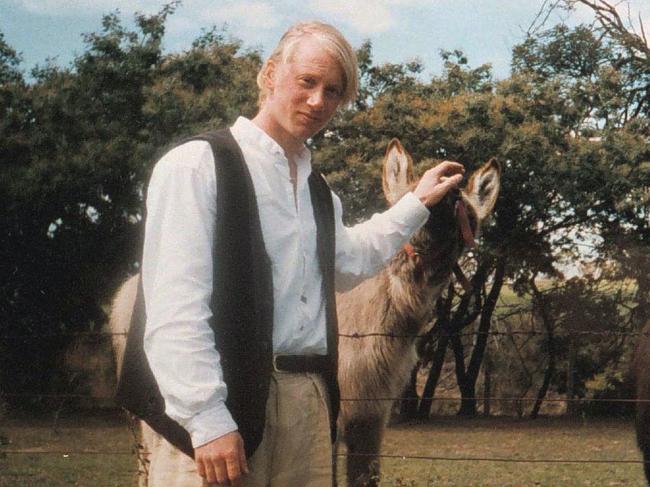

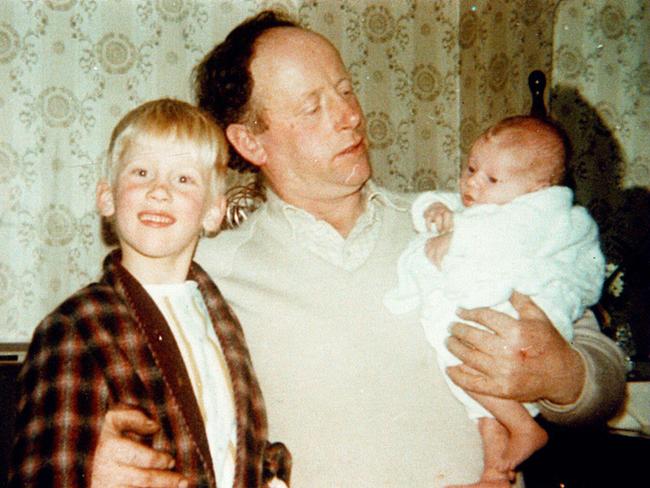

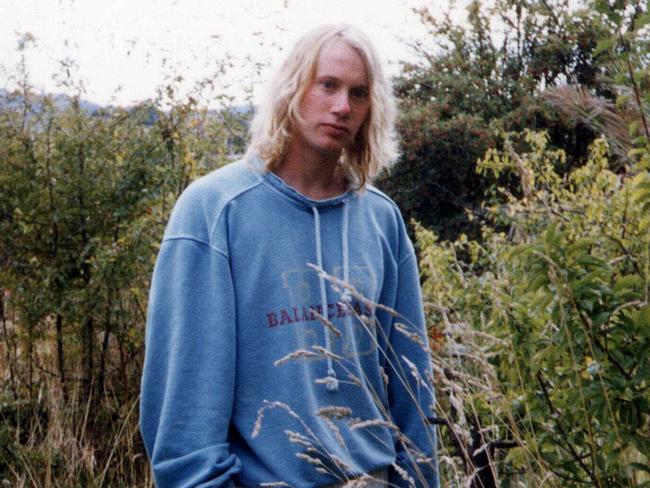

A lone gunman, armed with several military rifles, had walked into the Broad Arrow Café at Port Arthur at 1.30pm on that sunny Sunday, and begun shooting tourists and staff. He was later identified as Hobart local Martin Bryant.

By the following day, 35 people would be dead and 20 wounded. At the time, it was the worst modern-day mass shooting in the world, and would leave emotional scars that are still unhealed, 25 years later.

Rundle had to wait for the tiny single-engine plane, which had suffered a technical fault, to be fixed before he made it to Hobart and rushed straight into a briefing with the Tasmanian police commissioner John Johnson and Attorney-General Ray Groom.

“It was quite obvious by the time I’d left Devonport and got to Hobart that the situation had deteriorated and there was a very serious tragedy unfolding down on the Tasman Peninsula,’’ he said.

A young Legal Aid lawyer named Roland Browne was sitting at his kitchen table with a group of friends on that Sunday afternoon, working on plans to lobby the Tasmanian government to tighten up the state’s gun laws.

“I became involved in the late 1980s when a friend of mine drafted some legislation for Dr Bob Brown in ‘87 to introduce some gun laws into Tasmania because there weren’t any down here at all,’’ Browne recalled.

“A bit later the Hoddle Street then the Queen Street shootings occurred in Melbourne and my friend Paul Chatterton started a group that he called the Coalition for Gun Control in Tasmania and asked me if I wanted to be in it.

“Paul’s sister Lisa had been shot dead in Sydney a year, two years earlier, that was his interest in it.’’

So far, their efforts had amounted to little. A string of mass shootings, and just six weeks earlier, the murders of 16 schoolchildren and their teacher at Dunblane in Scotland by a lone gunman, had failed to convince the state and territory governments to restrict high-powered, rapid-fire guns.

They pushed on regardless, and the group around Browne’s table was prepping for a meeting with Tasmania’s police minister John Beswick in three days’ time to lobby for semiautomatic weapons to be banned when Browne’s phone rang.

Mike Stoddardt, a senior prosecutor with Tasmania’s office of the Director of Public Prosecutions, had been listening to the radio and heard reports of a shooting at Port Arthur. He rang to tell his wife Ros, who was at the meeting with Browne.

“We listened to it on the radio, heard what we could,’’ Browne said. He felt “numb and sickened.’’

He lived in Glebe, on the edge of the Hobart CBD and decided to walk into town and see if he could get in to a press conference about to begin in the Tasmania Police headquarters.

Hobart was a city under siege.

“They’d shut down Liverpool Street, blocked off all the area near the police station and the hospital, the helicopters were coming in to the Regatta Ground landing pad and people were being ferried from there to the hospital,’’ Browne said.

“I made my way to police headquarters and went in. I wanted to find out first hand just exactly what had gone on and what was going on. Then, as now, I was always interested to know what the gun was that was used.

“I missed the media conference – by the time I got there it was over.

“I saw the Premier Tony Rundle and the Attorney-General Ray Groom walking out, ashen-faced, absolutely ashen-faced.’’

Peter Hazelwood was Tony Rundle’s press secretary, and a former Sydney journalist. He didn’t accompany his boss to the press conference. He had undergone specialised “SAC-PAV’’ training – early anti-terrorism training under what was then known as the Standing Advisory Committee on Commonwealth and State Cooperation for Protection Against Violence – and his bosses decided to send him to Port Arthur to help out the police.

“I remember driving out of town from the city, out over the bridge and they were getting the Domain ready for the helicopters to bring in the injured,’’ he told News Corp.

“The hospital was on full alert and we still didn’t know who or what but we knew the death toll kept rising. At this stage I think it was 22.

“The big thing that hit me was just the enormity of it, 22 people dead at Port Arthur in Tasmania – was it a bus crash? No, someone had been shooting.’’

He spent the drive down the Arthur Highway trying to work out what had happened.

“There wasn’t a single car coming the other way. It’s a tourist highway and I thought this is a bit strange.’’

Hazelwood arrived at Taranna, a hamlet just outside Port Arthur, about 4pm to find police Superintendent Barry Bennett had commandeered the local Tasmanian devil wildlife park and turned it into a forward command post.

There was no mobile phone coverage, no internet, and just two phone lines.

The gunman was by now holed up in the Seascape guesthouse a short distance away, with three hostages and an arsenal of high-powered weapons.

“I’ve introduced myself (to Bennett) and he said ‘thank God you’re here, tell me what you want with the media and we’ll do it whenever and as often as you want. We will let them know everything we know’.’’

“It was really good to have a forward commander that was that prepared because the media had also arrived at this stage, so they must have driven faster than I did although I didn’t think anyone could.’’

Back in Hobart, Rundle and his colleagues were trying to get a handle on what the awful tragedy unfolding on one of their major tourists sites would mean.

“I knew once the full story had unfolded there would be a lot of things the Government would need to put in place … there were all sorts of things unfolding.’’

In and around the historic site lay the bodies of the men, women and children slaughtered by Bryant mainly using a Colt AR-15 SP1 Carbine semiautomatic rifle he’d been able to buy, despite not having a licence, from the local Guns and Ammo gun store down the road from his house in suburban New Town. It was exactly the kind of gun Browne and others had been trying to get banned.

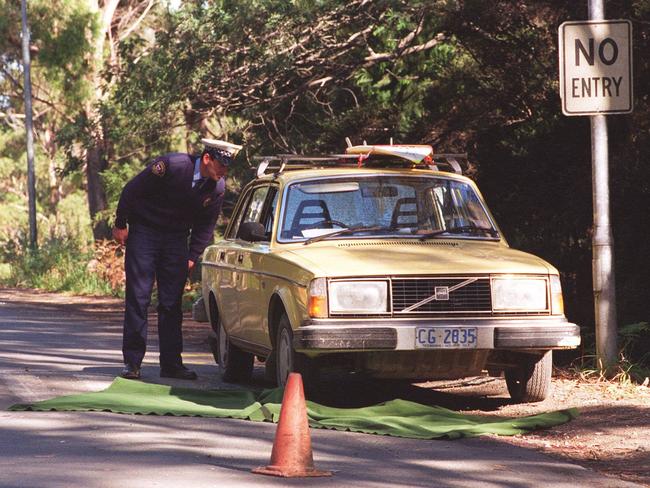

On the road into the site lay Nanette Mikac, the wife of local pharmacist Walter Mikac, and her tiny daughters Alannah, 6, and Madeline, 3, cruelly shot dead by Bryant as he fled the scene in his distinctive yellow Volvo.

As day turned into night, Bryant continued to fire at the Tasmanian Special Operations Group police who had by now contained him inside Seascape, where the fate of owners David and Sally Martin was unknown.

“The special squads of the Tasmanian and Victorian police who surrounded the Seascape cottage on the night of the 28th, they estimated that Bryant had fired about 100 rounds at them during the night. He’d also fired rounds at helicopters,’’ Rundle recalled

Barry Bennett handed over to Superintendent Bob Fielding as the night went on, and the police tried to work out their next step.

Hazelwood said Bennett and Fielding had to make “some really serious decisions.’’

“The fact was had the Special Operations Group stormed the stronghold as they may have done, the figure they came up with was 30 per cent losses,’’ he recalled.

“Bob had to decide: ‘do we kill another five people or are the hostages dead?’

“In the end it was courageous decisions from Bob and Barry and they stood Tasmania in really good stead in a time when it could have gone to hell in a hand basket really quickly.’’

At 8am the next day, Bryant set the cottage alight, and came out with his clothes on fire, where he was arrested and taken to the Royal Hobart Hospital, where many of his victims were also being treated.

Police discovered the Martins had indeed been killed by Bryant, as had another hostage, Glenn Pears, who had been kidnapped by Bryant at a service station some hours earlier.

With the immediate threat resolved, authorities now had to deal with the emotional, economic and political impact of the devastating terror attack.

For Rundle, that meant providing leadership for a state of just 470,000 residents, many in deep shock and mourning, its vital tourism industry brought to a virtual halt overnight, and which now found itself at the centre of a national controversy about gun laws.

In the days after the massacre, he invited Greens leader Christine Milne, with whom he governed in minority, to go with him to the Royal Hobart Hospital, where survivors suffering dreadful injuries from Bryant’s guns were being treated.

“I can remember the absolute fear still in the eyes of some of those people who were in bed recovering. The horror of what had happened there was just reflected in their personas and that was a moment that just made me realise what these people had been through,’’ he said.

“I still remember quite clearly the fear and the trauma was written all over their faces.’’

Hazelwood found himself in the unofficial role of providing government liaison to the families of the Port Arthur victims, including Melbourne woman Carolyn Loughton, who was grievously wounded, and spent years in and out of hospitals. Her 15-year-old daughter Sarah was killed.

He also got to know Port Arthur locals John and Sue Burgess, whose 17-year-old daughter Nicole was working in the gift shop when Bryant shot her dead. A note left by Sue to her daughter at the memorial cross quickly erected on the edge of the water at Port Arthur asked who would organise her now. This struck a deep chord for Hazelwood, who also had a highly-organised teenage daughter at home.

Three days after the massacre, Prime Minister John Howard and other politicians flew to Port Arthur to pay their respects and lay flowers at the Broad Arrow Café. The world’s media came too. The people of Port Arthur didn’t want the media spotlight, and Hazelwood had to negotiate some middle ground. He recalled some of the locals were “quivering messes.’’

“This is less than 48 hours after a huge massacre and they were standing outside the place where it all happened and they didn’t want to be filmed in that state and the media, to their credit, weren’t that keen on running that sort of footage either,’’ he said.

“From that day, I took up some sort of advisory role as a friend to some of the relatives.

“I was still trying to be press secretary to the premier of the state who had just had 35 people killed on one of his main tourist sites, and I was trying to help some of the people who were in need for advice, and I could point them in the right direction within government if they needed help or someone to talk to.’’

Browne knew the days after the massacre were pivotal, and he had to find the right way to give the final push needed to get gun control laws introduced.

He helped organise and spoke at an emotional anti-gun rally on the lawns outside Tasmania’s Parliament House in the days after the massacre, in front of thousands of people.

“I remember some of the things I said. I can remember I ended my speech by saying the gun lobby refers to these semiautomatic guns as bunny guns and I said we don’t want to be the bunnies.’’

Browne recalled the speakers at the rally and many of those in the crowd were on the edge of tears.

“There was also a spirit of hope. There was this combination of the depth of despair but hope because everybody knew the only answer to preventing this kind of event ever happening again was going to be tight gun laws.

“In fact it was the prospect of that which kept a lot of people above the waterline over the next month because it (the massacre) was more than most people could bear.’’

Howard, who, like Rundle, had only been in office a few weeks, read the public mood and declared the time had come to ban semiautomatic guns from the community and introduce heavy restrictions and uniform gun control laws across the country. It was the turning point.

Rundle supported him, and joined by Milne and Labor leader Michael Field, pushed for Tasmania’s fatally-flawed legislation to be fixed.

“Milne and Field acted very responsibly, as their parties did, and the Legislative Council also co-operated and basically gun laws were introduced and passed through both houses of Parliament without dissent,’’ he said.

“There was absolute unanimity which is a pretty rare thing in politics although this was, you could say, an unusual event with a lot of pressure on politicians to do something about it because basically Howard’s decision was popular amongst the average Australian.’’

The same pressure was being felt across the nation as each state and territory made the decision to join their colleagues in introducing new gun laws. In Sale, Victoria, Howard’s staff made him wear a bulletproof vest under his suit when he fronted up at a gun rally – something Howard immediately regretted. At a gun rally in Gympie, Queensland, an effigy of Deputy Prime Minister Tim Fischer was hung from a noose.

The deal was done to strike the National Firearms Agreement just 12 days after the massacre, although the states and territories needed months to get the law changes through their parliaments.

When they did, Rundle was among the tens of thousands of people who forfeited a gun, handing his .22 rifle, used for pest control on his cattle farm, over to local police.

He went on a national tour, taking with him the Mayor of the Tasman Peninsula Neil Noye and the then-chairman of the Port Arthur Historic Site Board, Michael Mazengarb, to convince tourists it was safe to return to Tasmania.

“We were dealing with the aftermath of Port Arthur for probably 12 months after the 28th of April. There was a lot to be done,’’ he recalled.

“The fact that Bryant had stolen the lives of 35 innocent souls including children and there were (20) injured and we were also conscious of the heroes of all of that, the staff on the site who’d had a dreadful time, the community on the Tasman Peninsula, the first responders, the police and of course the medical staff at the Royal Hobart Hospital and all the others who were either directly or indirectly involved.

“Obviously they were placed at the centre of our thoughts and the things we were doing following Port Arthur.’’

Bryant would eventually plead guilty and was given 35 life sentences. He will die in Hobart’s Risdon Prison.

“The initial shock, horror of it had dissipated a little bit although we were all conscious of the fact that it was a stain on the history of the place that would never go away and conscious of the fact that … we were getting international publicity for all the wrong reasons. About the man who had taken the lives of so many people,’’ Rundle said.

“Once he was sentenced that was in some respects a relief.’’

Hazelwood spent Bryant’s court case wrangling the media, and continuing to support the Port Arthur families.

At one highly-charged press conference at the Hobart Town Hall, he watched on as Ms Loughton, forcefully airing her concerns about the Federal Government compensation scene, took over the conference and threatened to take her clothes off to show her scars to the world.

The pair had a laugh about it afterwards.

It was also Ms Loughton who inadvertently brought Hazelwood to tears, after Bryant was finally taken away in a prison van to serve out his miserable life in jail.

“That was Carol. We were walking back up to where the health department was putting the Port Arthur people to make sure they were okay. And she said to me ‘you know, it doesn’t seem fair. I’ve lost everything and Bryant gets put in jail’.

“And I really hit me. That was her life, totally up-ended and she felt it unfair that Bryant got to live and just go to jail.

“And I remember, I think it all just hit me at that stage. It had been a long year and I thought ‘jeez how much more of this can we all put up with’ and that was it.’’

Hazelwood sat down on the sandstone wall outside the courthouse and cried. A cameraman swung his lens onto him. Veteran TV journalist Norm Beaman stepped in and told the cameraman to cease, saying “he’s one of us.’’

“It was probably realisation for me too that yeah, 35 people (have been killed) and behind each of those 35 people are other people and it just goes on and on.’’

Hazelwood stayed with Rundle until the Liberals lost office in 1998, then joined Tasmania Police as a media adviser until 2005, when he and his family went back to Sydney. In a former life he’d been a producer for John Tingle’s talkback show on Sydney radio. Tingle had started the Shooters, Fishers and Farmers Party in NSW, and Hazelwood went to work for them, sparking endless speculation from conspiracy theorists on the internet who viewed Port Arthur as a deep-state plot to de-arm the population, rather than the evil actions of a single, angry, pathetic young man with a high-powered rifle he was too easily able to get. Now retired, he lives in Brisbane.

For Browne, the signing of the Agreement wasn’t the end, but rather another step on a long and difficult path.

“It wasn’t long after that it became clear that the next job was to try and maintain it because it was under attack very early on. And also we realised that control of semiautomatic handguns had been overlooked and we started working on policy and trying to lobby to get tighter controls over semiautomatic handguns.

“It didn’t end up too well for people at Monash University in late 2002 – there was a shooting there using semiautomatic handguns and that led to an amendment to the National Firearms Agreement in 2003 to tighten them up a little bit for handguns.’’

The Coalition for Gun Control, now renamed Gun Control Australia, continues to push for states and territories to become fully compliant with the 1996 Agreement, and is seeking further tightening of laws involving hand guns.

They’re also looking overseas and hoping for change in the United States.

“That’s a very long-term project that one,’’ Browne, now 61, said.

“But a lots changed in America. The NRA (National Rifle Association) is on its knees, it’s being sued for bankruptcy and President Biden is talking about gun reform in America. There’s a lot to be done and if we can have a tiny bit of influence at what happens in America that would be a wonderful outcome as well.’’

More Coverage

Originally published as Port Arthur anniversary: Former Tasmanian Premier Tony Rundle recalls what he saw shocked the world