COWERING in a locked bedroom with his siblings and mother, Massimo “Max” Sica would never forget the sound of gunshots being fired through the door.

Long before his convictions for murder, Sica told a psychiatrist he was five when his volatile dad Carlo snapped and tried to shoot his family. But did the attack ever happen, or was it a misunderstanding, or was it the invention of a disordered mind?

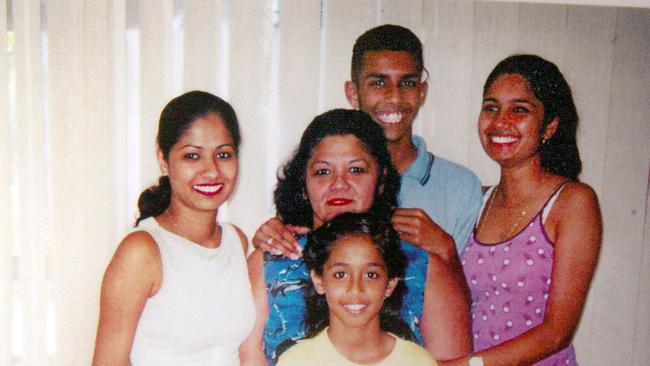

SINGH TRIPLE MURDERS: LAST SIBLING, SONIA PATHIK, DIES, AGE 43

MULTIPLE KILLER SEEKS PARDON WITH ‘FRESH EVIDENCE’

According to Sica’s family - his most strident supporters - the incident, recounted in one of his old psychiatric reports, never occurred.

“My husband never shoot through any door,” his Italian mother Anna Sica told The Courier-Mail in 2012, adding she doubted her son would make the claim.

It’s now been 17 years since the slaughter of siblings Sidhi, Kunal and Neelma Singh at their Bridgeman Downs, Brisbane, home.

Sica was found guilty of the triple slaying in July 2012 and was sentenced to life imprisonment, with a non-parole period of 35 years.

He unsuccessfully appealed the decision a few months later.

In the lead up to that appeal, The Courier-Mail obtained psychiatric reports from earlier offences that painted a sinister picture.

In 1993, more than a decade before the Singh killings, a prison psychologist raised the alarm that Sica displayed the hallmarks of a psychopath. At the time Sica was 23 and had a history of multiple offences.

THE MAKING OF A PSYCHOPATH

Criminal psychopaths are considered particularly dangerous because they can be superficially charming but also cunning, manipulative and devoid of remorse. Their lack of guilt makes them more likely to reoffend, some experts believe.

Not all psychopaths are criminals or even violent and research shows their traits can take them to the top of their fields as leaders in the corporate, political and sporting worlds.

Pathological lying, manipulation, emotional shallowness, sexual promiscuity, a lack of remorse or guilt, proneness to boredom and juvenile delinquency are among 20 factors found in people with the personality disorder.

Sica - well before the Singh murders - was found to have psychopathic traits which included difficulty controlling impulses, marked self-centredness, grandiosity and a broad-ranging criminal history.

Psychiatrist Ian Atkinson assessed Sica in 1999 when he was behind bars after a Molotov cocktail attack. His report details how a psychologist, Dr Tony Robinson, had previously assessed Sica around the time of his sentencing for a broad range of other offences in 1993.

“He (Robinson) found that the prisoner had significant personality problems and significant signs of psychopathy,” Atkinson wrote.

“This man quite clearly produces most of the symptomatology of a Borderline Personality Disorder, mixed with some features of Italian family loyalty.”

Borderline Personality Disorders cover a wide range of conditions, which can include pyschopathy.

Sica’s offending was traced back to his experiences as a child. He told Atkinson in 1999 that early tension with his father was behind his later anger with authority.

“What is very clear is that this man came from a very dysfunctional family,” Atkinson wrote.

“There were clearly lots of episodes of severe conflict between his father and his mother, resulting in her having a considerable amount of psychiatric treatment. His father was apparently aggressive towards the prisoner and, at times, threatened to kill him and other members of the family when he lost control of his temper.

“Sica states that, when he was about five years of age, his father tried to shoot the family. He recalls that his mother got the children into a room but the father fired bullets through the door. Years later his father shot himself but later recovered.”

In 2012, Sica’s brother Claudio and sister Roseanna, who believe then he was not involved in the Singh murders, denied the shooting incident happened. And his family said, despite the massive police investigation, no one has ever come forward to accuse Sica of violence in all the years leading up to the murders.

Sica subsequently developed a strong relationship with his father, who was also one of his key supporters in the years since the Singh murders.

A HISTORY OF CRIMINAL ACTIVITY

The family emigrated from Naples, Italy, to Sydney in 1970. His mother was pregnant with him at the time.

With his mother struggling to cope in Australia, the family returned to Italy in 1981, when Sica was 11, for two years.

The uprooted Sica was unable to adjust to Italian schools, which he viewed as authoritarian. He was relieved to return to Australia, where he graduated from Runcorn State High School in 1987.

An average student, he thought he could have done better at school. He told prison authorities in the 1990s that work in the family’s restaurant business had left little time for study. (Psychologist Robinson found he had an IQ of 102, which is regarded as about bang on average.)

While working in the family business he renewed friendships with old schoolmates and then joined them on a crime rampage which included break-and-enters and arson.

Wearing balaclavas and gloves and listening in to police radio networks, they disabled suburban electricity supplies so they could break into homes without alarms going off.

Members of the group would light fires at schools and businesses and then show up to watch emergency services respond to the blaze.

If police were slow to respond, Sica, who had a frustrated desire to be a cop, would phone them to see what was taking them so long.

In one instance after a group member was charged with traffic offences, they set fire to the police station in an attempt to destroy evidence. Sica blamed other members of the group for lighting the fires but, when charged with arson, pleaded guilty. Overall the group caused $365,000 damage.

Sica detailed some of the group’s crimes in letters to prison authorities in the 1990s when applying for early work release. He said one of his friends worked in a bank and had inside information about firms which kept money on the premises.

“We’d go over and break into them and take the money,” he wrote.

“There were also times when we just went out and did stupid things, like stealing cars, arson, smash and grabs and stuff like that.

“At the time we didn’t think of the consequences, we were just trying to impress one another. I think that we were just scared of not being in the group if we didn’t go along.”

He added he’d “never had a problem with alcohol, drugs or gambling” though had smoked marijuana with friends.

“I’m not proud of what I did, I never will be. I can’t change the past, but I can make sure it never happens again,” he wrote.

“I won’t commit any crimes again, I know that for sure. I stopped associating with my co-accused and my old friends a long time ago.”

Sentencing Sica in 1993 to nine years’ jail on 83 offences, the judge called it a “display of lawlessness on a grand scale”.

BAD HABITS DIE HARD

Released in May 1996, Sica’s good intentions were short-lived.

While still on parole, he was arrested and charged with throwing a Molotov cocktail at a house in October 1997.

Sica was married, had a young son, and was working at a computer firm at the time. His father was sick in hospital but instead of staying home with his family he met up with a former schoolmate and co-accused from some of his previous crimes.

A report from psychiatrist Dr Ian Curtis in 1998 details how the pair climbed a tree and smoked marijuana. Like two children, they played a stick-fighting game using wood from a broken chair and donned a balaclava from his friend’s car.

His mate told police he also had a jerry can full of petrol in the car and they decided to throw Molotov cocktails at someone “who had done the wrong thing by someone”.

A transcript from his parole hearing in October 1999 shows Sica, like with his earlier crimes, blamed his friend but also the additional influence of drugs and alcohol.

“I had a large amount of marijuana, like about 15 cones of marijuana and had a couple of Wild Turkey and Cola bottles . . . so when my co-accused lit his bottle I panicked, threw mine and ran and he just dropped his over the fence.”

Curtis had assessed Sica in Woodford prison in 1998 at the request of Sica’s then-lawyers, Boe and Callaghan.

“Essentially he presented as a disturbed individual in the sense of having a major malformation of his personality structure with ongoing difficulties with his inner controls and with his social limits,” Curtis found.

“This is a clinical presentation of gross immaturity with a relative lack of internal mental structures for self-regulation. His gross personality problems form a psychosocial backdrop which explains, in my view, the type of offending and the chaotic nature of his crime.”

While in prison for the Molotov cocktail offence and for breaching parole, Sica claimed he was injured in a series of falls. He prepared a legal claim against the State Government in March 2003, a month before the Singh murders, seeking almost $540,000 in damages.

An independent March 2005 medical report from neurosurgeon Dr Leigh Atkinson accused Sica of faking the injuries, raising the prospect of another significant invention.

“Mr Sica is extremely difficult to assess because of his inconsistent history and abnormal illness behaviour,” Atkinson wrote.

“I consider the symptoms he reports were due to a musculo-ligamentous injury to the lumber spine. I consider that under normal conditions these injuries would have settled and healed.

“In my view there is no anatomical basis for this persistent pain this man is complaining of.

“In my view Mr Sica’s injuries are out of proportion to the tissue damage. He impressed me as a physically very fit man and there were no signs of any neurological abnormalities. Mr Sica appears to be taking on a sick role for the advantages gained by sick people.”

In other parole documents, Sica dwelled on his troubled early relationship with his father.

“My childhood was both good and bad. I had everything I could ever want or need, except for some quality time with my parents,” he said.

“They were always working in the restaurant, so my brother and sisters and I never really spent much time with them.

“We grew up looking after one another and ourselves. We got regular beatings as my father had a very bad temper and he was easily angered.”