How Elle Edwards became one of many who are victims of the global cocaine trade

Elle Edwards was the only one killed in a shooting at a pub where the killer walked up with a machine gun that exposes a $7.6 billion dollar problem.

Cocaine Inc

Don't miss out on the headlines from Cocaine Inc. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Elle Edwards was meant to be wrapping Christmas presents with her dad.

But her phone pinged with a text.

The 26-year-old’s mates wanted her to come out for a drink.

It was Christmas Eve. They were at the Lighthouse Pub in Wallasey Village, on the Wirral peninsula, just across the water from Liverpool’s city centre in northern England.

Elle’s sister had been at the pub too, but drove home, telling her to be careful and not stay out too late.

As the temperature plummeted to freezing shortly before midnight, Elle, a dental nurse and beautician, went out into the beer garden at the front of the pub for a cigarette.

She didn’t know it, but a man with his face covered had been waiting near the pub for three hours with a Skorpion sub-machinegun, loaded with 12 bullets.

He chose the exact moment when Elle was having a smoke to walk up to that beer garden and open fire.

“It’s horrendous, you know, who goes to a pub with a machine gun on Christmas Eve?” her devastated dad Tim told the Cocaine Inc. podcast.

“This is not a video game. This is real life. If someone goes (to the pub) with a baseball bat and has a grievance with someone, that’s standard, that happens every weekend.

“But you go somewhere with a machine gun, doesn’t matter where it is, you’re gonna, you’re in there to kill someone.”

Listen to the Cocaine Inc. podcast below:

“That machine gun is not gonna just slightly hurt someone. So who the f**k goes there with that mentality?

“What part of your brain makes you think that that’s okay?”

Six people were shot on that cold Christmas Eve in 2022.

Elle Edwards was the only one killed.

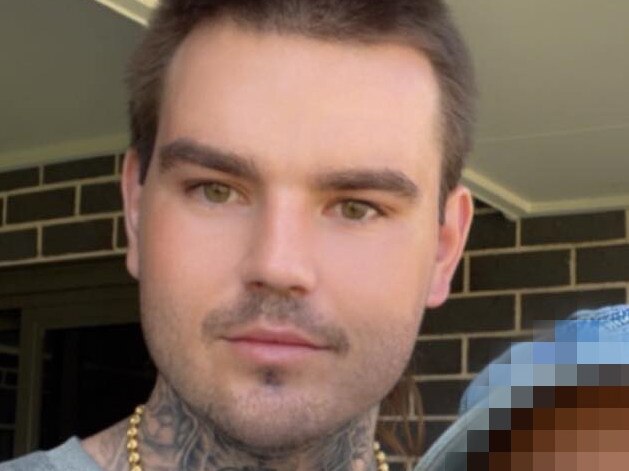

Connor Chapman, who was 22 at the time of the shooting, was sentenced to 48 years jail in July 2023.

That same month, five people were shot in five days in Sydney’s southwest.

Ahmad Al-Azzam, 25, was shot in the head while sitting in a silver Toyota in Mayvic Street, Greenacre at 2.15am on July 23. He died in hospital.

Kaashif Richards, 22, and Achiraya Jantharat, 19, were in another car about 50 metres away. The bullets sprayed them too, but they survived.

However Mr Richards, who was shot in the neck, will never walk again.

Criminal lawyer Mahmoud Abbas, 31, was the next victim – he was targeted in his driveway in the same suburb but the hit men failed at 10.30am on July 26.

Ferenc “David” Stemler, 28, was the fifth victim that week.

He was killed in a hail of bullets fired at him when he went out to meet two people at his rental property in Canterbury at 2am on Thursday, July 27.

There’s 17,031km between Sydney and Liverpool in the UK but there’s a direct line between these incidents – they were all victims of the cocaine trade.

True Crime Australia and the UK’s Times and Sunday Times travelled to 50,000km across the Netherlands, Dubai, Colombia, Mexico, Panama, England and Australia to investigate that trade.

The joint investigation has provided a unique insight into the cocaine trade and led to the Cocaine Inc. podcast.

Chapman, who is now serving his sentence in a British jail, was part of a cocaine gang that controlled the Woodchurch Estate, a working class area nine minutes drive from the Lighthouse pub.

His motive for getting into a Mercedes with blacked out number plates and firing at that pub was revenge – one of his mates had been beaten up the day before by a rival gang and he thought the perpetrator was there.

In Sydney, those shootings were part of 23 murders in three years linked to a dispute over a missing 400kg cocaine shipment which the criminals didn’t realise police had seized.

That was the start.

But as bullet casings kept falling onto Sydney’s streets, the reasons for the war blurred like smears of blood.

“When I first joined the AFP doing drug work back in the early 90s, it was Colombians, where the cocaine is produced, who would be responsible for the supply chain into Australia,” Assistant Commissioner Kirsty Schofield said.

“Colombian nationals in Australia would be in receipt of the cocaine. It was quite simple. That’s not the case anymore.”

Asst Comm Schofield said criminals “stayed in their lane”.

Everyone knew where they stood, territories and even crime types were clearly marked out.

Violence has always been part of the day-to-day operation of the cocaine business but in Australia it was behind closed doors in factories and warehouses, or at bikie clubs on industrial estates.

The victims would rarely, if ever, complain to police.

But the landscape has changed, and innocent members of the public like Mr Richards, Ms Jantharat and Mr Abbas are falling victim to the violence.

“What’s happening now is people are getting caught in the crossfire,” Asst Comm Schofield said.

Australia and the UK are, per head of population, the biggest cocaine users in the world.

Consumption has been rising fast despite the cost of living crisis that has seen soaring rents and the weekly grocery bill climb.

When the Spice Girls were top of the pops in the 1990s, regional areas in Australia were too out of the way for the cocaine dealers. All you could buy was a slab of beer and some marijuana.

Now country regions like Bendigo, the Barossa Valley, Dubbo and Toowoomba are among those smaller towns being flooded with cocaine.

Cocaine consumption in country areas was at record highs, according to an Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission report in March, 2024.

Globally, production of the high-altitude coca plants has doubled in the past decade.

If all the coca plants in the world were put in a 1km wide line, the crop would stretch from Melbourne to Cairns.

The spike in production which led to more and more cocaine being made available in Australia can be traced back to two decisions made in Colombia.

In 2015, Colombia, where about two thirds of the world’s coca plants are grown, ended a policy of aerial crop spraying to eradicate the plants.

Police had to pull out the plants by hand but the cartels protected crops with landmines. Colombia cops lost their legs.

In 2016, the Colombian government signed a 310-page peace deal with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), a guerrilla group that had been destabilising the country for 50 years.

However, there was an unintended consequence of that agreement.

FARC had controlled the cocaine market. They used the profits to fund their left-wing campaigns to overthrow the government, in what was labelled “narco terrorism”.

The guerillas controlled the market in the same way that Pablo Escobar’s Medellin cartel and the Cali cartel did in the 1980s and 1990s.

Their departure created a power vacuum, and an open market.

New players moved in to Colombia. The Mexican cartels came down, while the Balkan mafia moved in too, along with the Ndrangheta, Italy’s most powerful mafia group.

Hells Angels and Comanchero bikies from Australia grabbed their passports too, stopping at the airport lounge in Santiago, Chile, before landing in Colombia’s capital Bogota to set up direct supply lines.

The cocaine labs, where the leaves are cut up, dunked in petrol and hydrochloric acid to separate the active ingredient cocaine hydrochloride, also improved.

But cocaine prices in Australia stayed high, partly because of an Aussie cartel that drip fed the drug onto the market and demanded dealers maintain a floor price.

The iPhone has also changed the cocaine industry, with encrypted apps making it easier to co-ordinate deals in real time across the globe.

Some apps were more secure than others.

The AFP and the FBI set up their own app, AN0M, which was supplied to Australian kingpin Hakan Ayik.

He gave it to his friends; thousands of the handsets were sold around the world.

Criminals spoke openly because of their “secret” app was disguised as a calculator.

But the police were listening. They stopped 21 executions before they revealed they were the app’s puppet masters.

There are still dozens of cases before Australian courts based on evidence gathered in the app.

Those police successes have taken out some pivotal players – Ayik was arrested in Turkey last year on drugs and money laundering charges.

But the business still has smaller players keeping the cocaine flowing for the criminal cartels.

Law enforcement call them doors – people with security clearances at ports and airports who can green light a container carrying cocaine, or get a bag of cocaine on the correct carousel to escape border officers.

One of those doors was Cees, a former corrupt dock worker in Rotterdam who agreed to speak on condition his name was changed.

He said drug smuggling was happening “in plain sight” on the docks in the Netherlands, Europe’s largest port.

“Everybody who was working in the port knows it, you hear what’s coming in. You see how some companies are growing, which is impossible, that they’re growing so quickly,” he said.

Cees’ step across the line was unintentional at first.

A friend asked him to help move a container.

“At that moment, we didn’t know anything about the drugs. Later on they came to the office and they put up a bag of money in there for the success,” he said.

“And well, then I knew it was drug transport, of course. From that time on, that was easy money. Quick money.”

He made enough money to buy a house, but eventually he was relieved when he was caught and sentenced to six years jail because he could not see a way out of the trade alive.

Dutch gangs have become increasingly ruthless.

The severed head of Nabil Amzieb, 23, was placed outside a cafe in Amsterdam at 7.30am on March 9, 2016 as a targeted warning sign. He was a victim of a drug feud.

Police in the Netherlands also found a torture chamber in a shipping container buried in a forest in Wouwse Plantage, a 90-minutedrive south of Amsterdam.

The plastic lined, soundproof container had a dentist’s chair with two leather straps for each arm and metal handcuffs for victims’ ankles.

Pruning shears, scalpels and pliers were also found.

Cocaine wholesaler Roger P, also known as Piet Costa for his frequent trips to Costa Rica, was jailed for ordering the torture chamber to be built.

A Dutch court heard he planned to kidnap rivals, as well as members of their families, and torture them in the container.

He was jailed for three years for that crime, on top of a 15-year sentence for cocaine trafficking.

Roger P made hundreds of millions of euros from the cocaine trade, disguising his goods as pineapples.

A court heard he had planned to bring in 25 tonnes in one shipment.

But those profits cannot be put straight into a bank. They need to be explained, legitimised so they cannot be seized by police.

Casinos have been traditional targets by money launderers. Melbourne’s Crown Casino almost lost its licence after video emerged of criminals laundering hundreds of thousands of dollars pulled out of an Aldi bag at its posh Mahogany room.

In Australia alone, the cocaine market generates more than $1 billion each year, while drug cartels make £4 billion (A$7.6billion) in the UK.

That creates a problem.

An organised crime group in Yorkshire, northern England, came up with a simple, effective way to launder more than £100 million (A$190 million).

Glamorous beauty salon staff would get the train down to London, meet a driver at a Starbucks cafe, who take them to another address where suitcases packed with cash would be collected.

They would take the bags – in some cases seven per person – to Heathrow Airport for a business class flight which allowed for extra baggage.

And they were told to arrive close to the plane’s departure time so they would be rushed through security. When they landed in Dubai, they simply declared the money on arrival at the airport, giving it a paper trail that allowed criminal networks to deposit it into banks.

The cash mules were paid £3000 (A$5700) each and had an all-expense paid trip in five-star hotels in the desert oasis.

They were named the Sunshine and Lollipops gang, in reference to the name of one of their WhatsApp chat groups.

The mules included Kim Kardashian look-a-like Tara Hanlon, 31, who bragged about her trip on social media when she was in Dubai at a £500 a night (A$950) hotel.

“And this bad boy is the balcony, look at that view,” she said in a video released by the court.

“So the Five has its own beach basically, so that’s where I’m going to be spending most of my time.”

The ringleader of the group, Abdullah Alfalasi, was jailed for nine years in July 2022.

In March, he was ordered to pay £3.5 million (A$6.6 million) – the amount police allege he made from the scheme – or facean additional 10 years’ jail.

Alfalasi was from a wealthy family – his wife had a flat in London’s Belgravia, just down the road from Harrods.

In London and in Australia, particularly in Sydney, cocaine has become part of a weekend.

“I know a lot of people will do cocaine in front of their children. They will have a barbecue and their friends will come around. They will have a few beers, a few wines and a few lines,” a former drug dealer in Sydney’s eastern suburbs, said.

“They think it’s okay but I thought it was wrong, I would never do that. When you’re on it you look and act completely different.”

For every gram of cocaine sold for more than $350 in Australia, up to $100 of that goes to the dealer.

That’s why many offer personalised service, straight to your door.

“They would come by foot or by car and then you give them the money and you say sayonara,” a male Sydney user said.

Another user said they could tell the quality of the cocaine because of its appearance.

“It should be like icing sugar,” the female user said.

But the former drug dealer said users were overconfident.

“It doesn’t come with instructions, there’s no warning labels. It’s easy to take too much,” the dealer said.

The Australian Capital Territory decriminalised cocaine in October last year.

Anyone caught with small amounts of cocaine now receives a $100 fine and gets directed to a health service instead of going to court and risking a conviction.

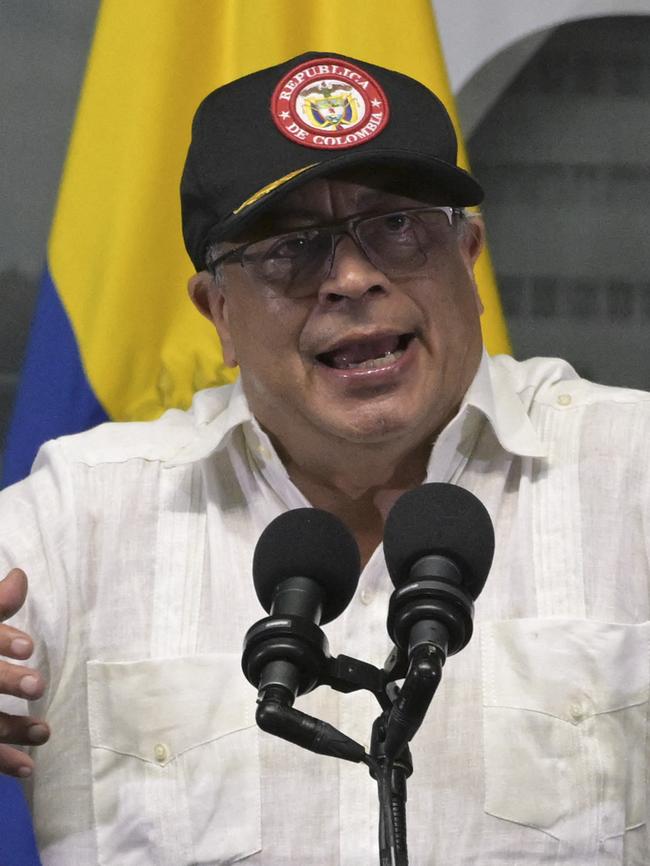

Senior police in Australia have been closely monitoring the results of the changes. It’s also being monitored in Colombia where the nation’s first left-wing president Gustavo Petro said in his inaugural address that the “war on drugs had failed.”

He had promised a more lenient approach to repentant drug dealers, decriminalising coca leaf production and even offering cocaine snorting rooms, similar to safe injecting rooms in Australia.

Mr Petro has denied he received money from drug cartels to fund his election campaign.

However, his son Nicolas was due to face court in Colombia this year over accusations from his ex-wife he received A$150,000 from a cocaine kingpin now jailed in the United States.

Nicolas Petro has denied all charges against him, but prosecutors alleged he could not afford his A$75,000 Mercedes Benz on his salary.

Alfonso Valdivieso, who was Colombia’s Attorney-General between 1994 and 1997 and pressed charges against the then president over allegations he used money from the Cali cartel to fund his election campaign.

In his case, the president was acquitted following a vote in Colombia’s parliament.

“It’s not as simple as legalise the problem because in Colombia that would just create other problems,” Mr Valdivieso said.

“We need, without any doubt, to continue to confront and attack these organisations.”

Back in Liverpool, Tim Edwards doesn’t have any answers.

“I don’t think it’s something we’re ever going to get rid of,” he said.

“It’s pretty much ingrained in society now, the cocaine trade and the use of cocaine.”

His life changed forever when Chapman pulled the trigger on that Skorpion machine gun.

“I always explain it as being in an elevator that doesn’t stop at any floor, just keeps going up, and it doesn’t stop.

“You’re just in this box, you’re in this bubble or whatever you want to call it, and it just moves at a thousand miles an hour. And there’s no way you can get off.”

More Coverage

Originally published as How Elle Edwards became one of many who are victims of the global cocaine trade