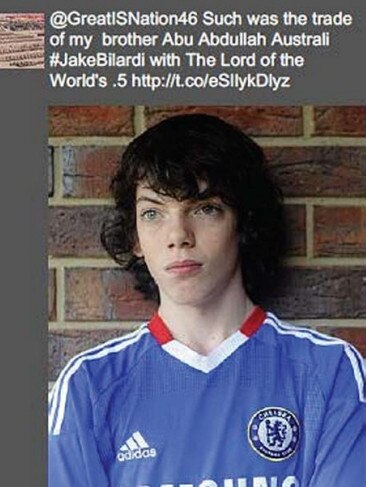

For months, Jake Bilardi had been scouring the internet for a ticket to join Islamic State.

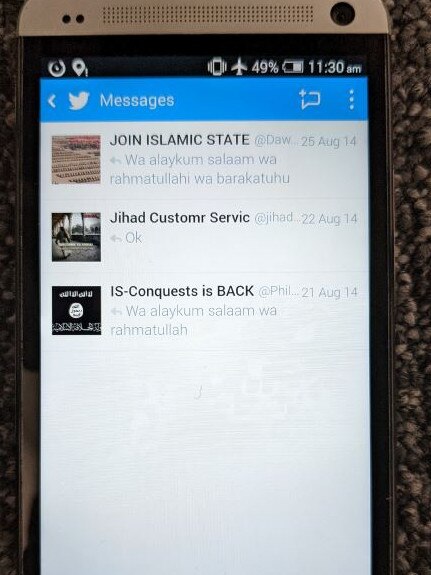

So by the time the teenager found @Dawla_NewsMedia, the propaganda Twitter account operated by Mirsad Kandic, he got straight to the point.

“Are you in al-Sham now?” Bilardi asked, referencing Syria.

“Are you able to organise a contact for me? Someone who I could meet in Turkey and who could bring me into Syria inshallah?”

Kandic, a Bosnian from Brooklyn, could relate to his desperation.

It had taken him 18 months to make it to Syria, having been blocked from several flights because he was on a no-fly list.

Upon arriving in December 2013 – via a two-day bus trip to Mexico and flights through Panama, Brazil, Portugal, Germany, Kosovo and Turkey – Kandic was tasked with spearheading Islamic State’s social media operations and smuggling in foreign fighters.

He was just the ticket for Bilardi.

Initially, Kandic tested his bonafides, asking if he knew anyone in Syria, where he was from, if he was married and when he planned to travel.

But within an hour, he was offering Bilardi a road map to becoming a terrorist.

“When you are ready let me know,” Kandic said.

“Until then learn Arabic as much as you can if you don’t speak it already.”

Bilardi wondered whether frontline training required a “very high fitness level”, and how much money he needed to bring.

“We do exercise but you should fiscally be able to run 2-3km without stopping,” Kandic replied.

“You should have a minimum 500$ … Over here we carry US Dollars because you can exchange them anywhere you want.”

Hear a re-enactment of a conversation between Jake and Mirsad below:

He offered Bilardi a price list of Islamic State essentials, including $1500 for “your regular schoolbook” – a reference the Australian already understood to mean an AK-47.

Four hours after their conversation started on June 3, 2014, Bilardi asked Kandic: “Could you tell me what your role in the mujahideen is?”

“I can’t tell you that brother I hope you understand,” Kandic replied.

“We don’t know each other yet.”

That changed quickly over the weeks ahead.

Bilardi was keen to travel “as soon as possible”, but he said he was “getting a little nervous because it seems Western governments and Turkey are cracking down on foreigners going to Syria”. The recruiter reassured him with further advice.

“Let me know few days in advance so I can arrange things for you,” Kandic offered.

“You are a turist (sic) on vacation in one of the most visited place in Asia called Istanbul :).”

But he also had a warning for his prospective recruit: “Remember that this is not the place where you can get in and out as you wish.”

That did not slow Bilardi down. By August 18, with his passport issued, his visa approved and his flights booked, Bilardi told Kandic he was due to arrive in Istanbul a week later.

“In shaAllah you have allot of fun in your vacation,” the recruiter said.

In the days before Bilardi departed, Kandic reminded him to unlock his phone so it could be used with an overseas SIM card, to bring enough clothes to “look legit”, and to leave any laptops and tablets at home.

Most importantly, he arranged for someone to meet Bilardi at the airport.

Watch the never-before-seen CCTV of Jake leaving Australia for Iraq:

“The brother will be there for you,” Kandic said.

“When you exit from the airport and you reach where the people are waiting for there loved once walk to the right side.”

“There will be a phones booth. stand or sit next to it.”

“The brother will say that I sent him.”

Bilardi followed every word of Kandic’s instructions. Seven months later, he was dead.

EVIL MASTERMIND’S ACT

Earlier this year, in a New York courthouse, Assistant US Attorney Matthew Haggans pointed to these messages as he summed up the case against Kandic, who he declared had turned Bilardi into a “powerful, deadly terrorist”.

“How did that weapon get to that place in Ramadi, Iraq, from a tidy bedroom in a suburb of Melbourne, Australia halfway around the world? The defendant made it happen,” he said.

“He didn’t build the bomb. He didn’t gas up the truck. He did something much more important – the defendant helped provide ISIS with the bomber.”

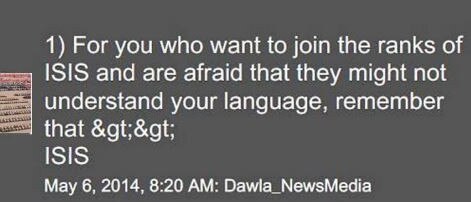

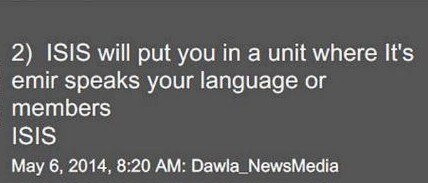

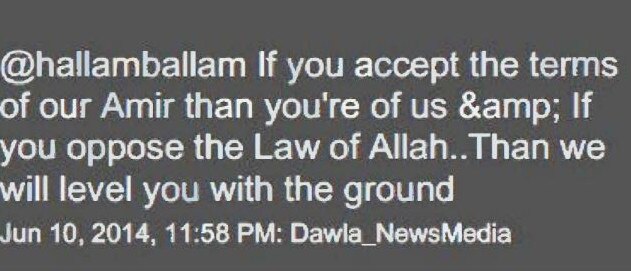

It was an act Kandic perpetrated hundreds of times through a network of more than 120 Twitter accounts he used to share recruitment messages and gruesome propaganda, including an infamous execution video – in which victims were forced to dig their own graves before being shot – Kandic said was the “best thing ever seen on screen”.

“Kandic helped to build a secret supply chain of willing fighters for ISIS, recruiting them over social media and ensuring their illegal transit into Syria so they could wage war,” FBI Assistant Director-in-Charge Michael Driscoll said.

The terror mastermind is now awaiting sentencing.

Major update on Janine Balding murder case

A new DNA test will be conducted in the investigation into Janine Balding’s horrific murder, as jailed killer Stephen “Shorty” Jamieson fights for his conviction to be quashed.

Woman claiming to be Madeleine McCann arrested

A Polish woman who claims to be missing British toddler Madeleine McCann has been arrested at a UK airport.