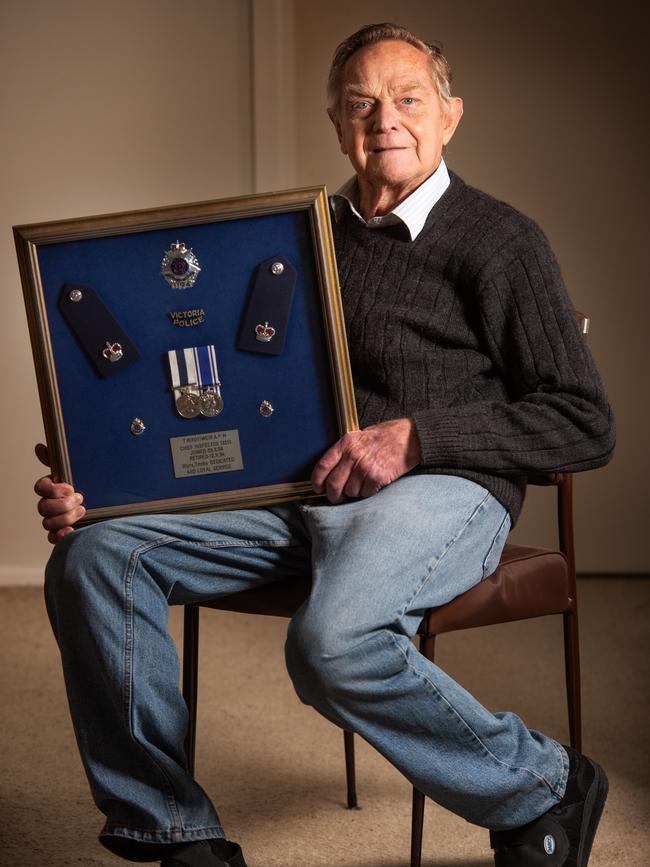

Behind the lines: The cases former crash investigator Roy Weir will never forget

Police officers often remain matter-of-fact about the tragic and often grisly things they see and do on the job. One officer recounts the worst cases he witnessed during his long career in the road accident squad.

Behind the Scenes

Don't miss out on the headlines from Behind the Scenes. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When Major-General Selwyn George Porter was appointed chief commissioner of Victoria Police in 1963, the death toll on the state’s roads was 540. Another 13,182 Victorians were injured.

About the same time, a 20-year-old motor mechanic from Shepparton who’d joined the force a couple of years earlier made his own commitment to do something about the state’s “epidemic proportions” road toll.

Roy Weir spent the next 30 years investigating traffic crashes all over Victoria and was awarded an Australia Police Medal in 1984 for the role he played in the extraordinary reduction in Victoria’s road toll since the early ‘70s, when The Sun newspaper began its 1034 road safety campaign.

But he still doesn’t know who named the squad he worked for in the early days — or why.

“In those days it was called the Accident Appreciation Squad, which was totally inappropriate really. There wasn’t much to appreciate at the scenes of most of the fatalities we attended, although the families of hit-run victims did appreciate our efforts to catch the driver.

“At some stage it became the Accident Investigation Section, and since I retired it’s switched again and become the Major Collision Investigation Unit, which is staffed almost entirely by detectives.

“Anyway, we must have been doing something right over the years if the figures mean anything”. (Victoria’s annual road toll last year had been cut to 266).

Now 83, Weir has been a Type 1 diabetic for over 50 years and says that “by rights I should have been pushing up daisies long ago”. He had the lower part of his right leg amputated last year, and had to go back in to hospital last week for an operation on an infected ulcer on his left foot, which had not healed since the first operation.

Despite his advancing years and his matter of fact approach to life, details of some of the hundreds of cases he investigated still spring far too readily to mind. One of them, when a family was wiped out in a moment of madness near Ballarat, was a nightmare he’ll never forget.

“There were six people from one family killed in a Valiant sedan that was hit head-on by a flour truck. What made it even worse was that one of the women was pregnant and there was actually seven dead,” Weir said.

“The truck driver and his mate, who was also driving a flour truck, were on their way back to Ballarat after making a delivery, and decided to stop at a pub for a couple of drinks.

“After they left the hotel the back one tried to overtake the other one and they finished up side-by-side, racing. The Valiant was coming towards them, but that made no difference.

“The overtaking truck driver was taken to Ballarat Hospital, where he rang his girlfriend from the casualty section and told her to bring in a flask of whisky, which he drank to try and cast doubt about his blood alcohol reading when it got to court.”

Both drivers faced court on six counts of culpable driving and were convicted, but their sentences of two years jail on each count were made concurrent.

“That’s what it was like in those days — two years was a ‘good’ penalty,” Weir says, welcoming community-driven increases in sentencing for serious driving offences.

“These days culpable drivers are getting six or eight years for bad ones. That’s more like it.”

(Culpable driving causing death now carries a maximum penalty of 20 years’ jail. It is a category 2 offence, which means automatic imprisonment except in special circumstances.)

In another of his culpable driving cases, this time involving a trailer not a truck, Weir says he “didn’t get a result in court, but did get the law changed”.

“We charged this bloke who’d bought a second-hand boat and trailer and gone fishing down at Paynesville. On the way home a bearing collapsed and moved the wheel off the car as he went through Bairnsdale.

“The U-bolts and the spring were dragging along the road and a piece of hot metal flew off into the grass on the side of the road and started a fire. The driver stopped, but couldn’t put the fire out and in the subsequent fire a firefighter was burnt to death.”

Although the driver was cleared of culpable driving, the presiding judge called for a change to the law in those circumstances to require not only the towing vehicle to be roadworthy but also the vehicle being towed.

Weir remains matter of fact about the tragic and often grisly things he had to see and do during his long career.

“We’d have to go down to the Coroners’ Court, undress the victim and bag everything up for forensic examination. If it was a hit-run we’d have to take fingernail clippings, blood and hair.

“One time I was examining an MG and finished up with half a bucket of human remains, but in those days there was no such thing as unwinding, or time off if you were stressed by handling body parts or that sort of thing.

“Nobody had ever heard of counselling. You just went and ate your sandwiches and went on to your next shift. That was the way it was in those days”.

MORE FROM GEOFF WILKINSON:

BOGUS BARRISTER SARAH GRASSO’S ELABORATE WEB OF LIES