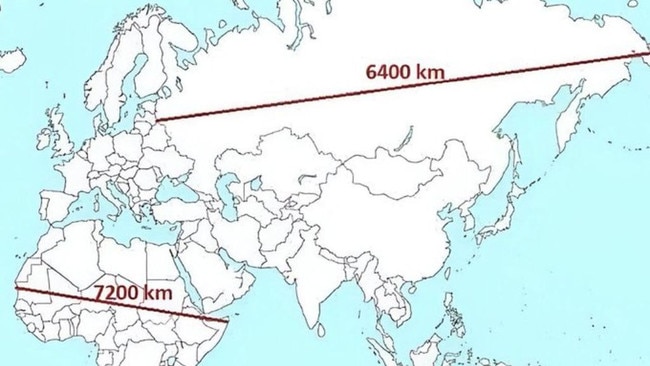

1/26A mind-blowing image comparing the width of Africa and Russia is going viral, and it’s flipping everything people thought they knew about geography. It shows Africa stretching 7200km across from west to east — farther than the 6400km between Europe and eastern Russia. Yet on most maps, Africa looks smaller. It’s left people wondering: why? Picture: X