Thermomix, Dyson, HTC: The ethical problem with our electronics

THE true cost of your addiction to electronic devices isn’t necessarily counted in dollars and cents. This is what you’re not considering when you shop.

Business Technology

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business Technology. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IT IS the dirty price we pay for our electronic goods.

But while products like the Thermomix and curved televisions and shiny fridges may make our lives easier, it comes at a high price.

A Baptist World Aid’s Electronics Industry Trends report has revealed the true cost of our love affair with all things electronic, with most companies in Australia unable to determine whether raw materials used in their products were obtained using slave labour.

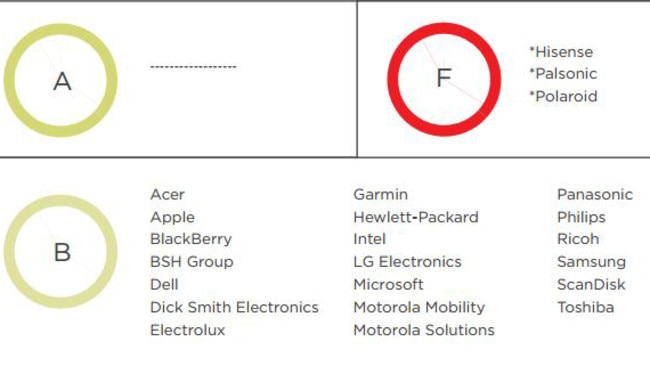

The report graded 56 companies from A to F on the strength of their labour rights management systems to mitigate the risk of forced labour, child labour and exploitation in the supply chain.

It found 64 per cent of those surveyed showed some improvement while 9 per cent showed significant improvement compared to the previous year’s report, including Dick Smith, BlackBerry and Garmin.

However, not one company was awarded a grade in the A range with the median grade for companies being a low C-.

Hisense, Palsonic and Polaroid were named among the worst offenders with an F rating, while Vorwerk, owners of the popular Thermomix, were awarded a D-.

The kitchen appliance which is a super-high-tech food processor, combining 10 appliances into one unit, has developed a cult following in Australia.

“Vorwerk, the manufacturer of Thermomix, did not participate in the Baptist World Aid

survey,” Vorwerk said in a statement.

“Giving a company a D rating because they chose not to participate lacks validity.

“Thermomix in Australia is committed to fair work practices and improving the health and

wellbeing of Australians through education, charitable partnerships and the empowerment

of communities.”

The report reads: “Disappointingly, a number of Australian brands including Kogan, Soniq and Palsonic were among the worst performers receiving D- and F grades.”

Dick Smith, which is now in receivership, was named as the Australian stand out moving from a D grade to a B- “reflecting increased disclosures about traceability and proof that workers in its first tier factories were receiving wages above the minimum”.

Other popular companies and brands including Breville, Hitachi and Sony were awarded a C.

Among the companies which failed to be transparent or take part in the survey included Dyson, Whirlpool and Kogan which were slapped with a D along with Capital Brands.

Surprisingly, tech giants Apple, Microsoft, Acer, Intel, LG and Samsung all received a B+.

Apple was named as among one of the most proactive in managing its supply chains, although the report noted there was still a lot of work to be done.

In March last year, shocking footage emerged of Apple workers being exploited at Pegatron, an electronics manufacturing company in China where iPhones and iPads are assembled.

The footage shot in secret as part of a BBC Panorama investigation revealed workers being “treated like prisoners” and “forced to sign work sheets that show them agreeing to long hours of overtime”.

In 2010, Apple found itself in the news again following the suicides of 14 workers at a separate Taiwanese Apple production factory, Foxconn, with the tech giant talking up its promises to take the rights of its workers seriously, including improved working conditions.

On its website, Apple maintains it is committed to building its products “in ways that are ethical and environmentally sustainable” by creating programs that “educate and empower workers”.

Tom Godfrey, a spokesman for consumer advocacy group Choice admitted many shoppers remained confused over what constituted an ethical choice when it came to buying electronic goods.

Mr Godfrey said when it came to appliances, a big brand or a high price tag is no guarantee of a more ethical purchase.

“Some of the better companies are more transparent about their supply chains and invest more to help consumers make an informed choice,” he said.

“Notwithstanding perceptions around price, if a company fails to audit, manage and disclose its supply chain, it is very difficult to determine if you are making an ethical purchase.”

It also found 60 per cent of people expressed concern over the materials used in the production process.

While more expensive may not necessarily mean you’re buying an ethically made product, Choice found bigger brand names were often better placed to seek out appropriate certification, develop codes of conduct and pay for independent audits.

Hannah Harborow, campaigns manager for Amnesty International, said it was disturbing that some of the world’s biggest consumer electronics firms were not able to say how and where they trace their raw materials from.

“The evidence we found suggests there is a high risk that big name companies are using cobalt mined using child labour in the DRC because they are failing to do basic checks,” she said.

“Companies need to make sure that their operations are not linked to human rights abuses but they can’t just walk away — they must address the abuses that child and adult miners have suffered and do what they can to improve the conditions of those who work in their supply chains.”

Originally published as Thermomix, Dyson, HTC: The ethical problem with our electronics