Undercover footage shows how ‘pig butchering’ romance scam takes unsuspecting victims’ money

Incredible undercover video has revealed the inner workings of a “devastating” scam operation, where real-life models lure unsuspecting victims.

Security

Don't miss out on the headlines from Security. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Incredible undercover video has revealed the inner workings of a “pig butchering” scam operation, where real-life models are recruited to lure unsuspecting victims.

Jim Browning, a software engineer and YouTuber from Northern Ireland who makes videos tracking and identifying scammers, worked with an insider who infiltrated a scam operation based in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, and was able to obtain undercover video and audio.

The 16-minute video reveals the inner workings of the pig butchering scam, which is a combination of a romance and investment scam, typically involving cryptocurrency.

Also known as romance baiting, the term pig butchering refers to a months-long scheme to “fatten up” victims on the premise of a fake relationship before “butchering” them with fake investment advice.

Although pig butchering scams originated in China, the lucrative method has been used to extort large sums of money from Australians, with perpetrators often finding targets on popular dating apps or through WhatsApp.

“The people in this office are pretending to be glamorous models in the hope they can steal money from people all over the world,” Mr Browning says in the video.

“But thanks to an insider who’s risking his life taking these pictures, we’re able to see how the scam operates. And if you’ve ever wondered why people are convinced by scams like this, take a look at this footage. Yes, they even employ models to FaceTime their victims.”

The footage shows a young model sitting on a couch speaking to a victim on video chat.

“Nice to see you — I will message you WhatsApp, OK?” she tells the man.

The scam operation was tracked to a set of eight-storey buildings several kilometres outside of the city, where “hundreds” of people were involved in the global scheme so extensive it required a dedicated communications van outside to handle traffic from so many mobile devices.

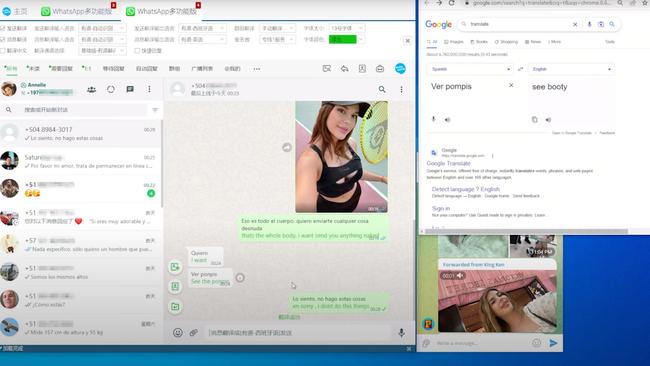

Inside the offices, rows of computers are set up with multiple dating and messaging apps — combined with VPNs to appear as if they are in the same country — which the scammers use to hunt for potential victims.

“At the start of every day it’s exactly the same, the scammer will pick out new potential victims,” Mr Browning says.

“You can see here who he’s pretending to be. It will always be someone glamorous with a rich-looking lifestyle.”

The scammer has a text document on his computer that includes a reminder of his fake persona, “Irene”, a script for interactions, and a list keeping track of potential victims.

Mr Browning notes the scammer will always ask the victim to move the conversation to WhatsApp or Telegram, as most dating apps have safeguards that detect suspicious behaviour.

“Only as I watched these scammers did it become apparent that this scam was truly global,” he says.

“I personally witnessed this group trying to scam people in South America like Bolivia and Peru, right through to obscure countries like Uzbekistan and Azerbaijan. They didn’t care how poor the people were, they were commissioned on how many people they got to sign up.”

According to Mr Browning, the person who filmed the video initially thought the job was legitimate, but when he realised it was a scam operation he decided to take the undercover footage.

He said the majority of workers inside the centres were migrants from North Africa or South East Asia, but the “vast majority” of the bosses running the operations were from China.

“It’s not clear why they’ve moved this scam from their traditional countries of Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos, but they’re now in Dubai,” he said.

Like many migrant workers in cyber scam centres in those countries, Browning said the workers were virtually held hostage as slaves with their passports taken away and strict rules governing their movements.

“The scale of this operation was incredible,” he says, estimating there may be as many as 1000 people involved.

The workers are provided with extensive scripts to copy and paste to potential victims, with pages of pre-written messages covering days of interactions.

“This is a copy-paste job, it’s very easy,” a recruiter is heard telling the undercover scammer on a phone call.

They are paid a base salary of 1500 dirham ($630) per month, but face dismissal if they get no new “clients”.

One new victim per month increases the salary to 2000 dirham ($840), while luring 20 new people into the scheme could see them earn as much as 6500 dirham ($2700).

New clients are defined as someone who gets to the second stage of the scam, investing money in a fake cryptocurrency app.

That’s where “Annelle” comes in, a glamorous Ukrainian model who hops on FaceTime to speak directly to any victims who might be unsure if they were talking to a real person.

She told the undercover agent she was paid 8000 dirham ($3400) — but complained she was unhappy with her salary and wanted closer to 25,000 dirham ($10,500).

“That’s why I’m leaving,” she says. “But I’m not an escort. I have family so I don’t want my family to see me in a porn website.”

Victims are asked to download a fake cryptocurrency app called Yomight, which appears genuine with a social media presence, YouTube videos and fake app store reviews.

The app tricks users into transferring crypto to the scammers’ accounts while making it appear as if the user’s balance is increasing.

“You’ll only really find out that it was all a scam whenever you attempt to withdraw large amounts of money,” Mr Browning says.

“The number one rule is, if it seems much too good to be true, then it almost definitely is.”

Scamwatch received 484 reports of romance baiting scams targeting Australians in 2023, according to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC).

Despite overall losses nearly halving, Australians still lost more than $40 million to the scam last year.

Pig butchering scams disproportionately impact people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, with reports to Scamwatch from these communities accounting for more than 30 per cent, or $12 million of total losses in 2023.

“Scammers are cold-hearted criminals who are looking to exploit people’s emotions in order to take their money,” ACCC deputy chair Catriona Lowe said in a statement earlier this month.

“We are urging people to not take financial or investment advice from someone you have only met online. Even if you think you know who you are messaging, remember that it could be a scammer on the other side of the screen.”

Ms Lowe warned that these scammers “will spend weeks, even months, messaging their victim, making them feel like they’ve formed a genuine connection before shifting the conversation to investment or cryptocurrency opportunities”.

“Ultimately, these ‘opportunities’ turn out to be investment scams, leaving the victim not only broken hearted but out of pocket by significant amounts of money,” she said.

Australians aged over 55 years old suffered the highest individual losses to romance baiting scams in 2023.

“While the decline in annual losses indicates that co-ordination between government and industry is increasing community awareness and disrupting scammers, we are concerned that people are still losing an alarming amount of money to romance baiting scams,” Ms Lowe said.

“Online dating and social media connection is a common way to meet new people, but it also presents an opportunity for scammers to deceive people and take advantage of their trust. We are working closely with law enforcement to combat these scams and protect the public.”

How ‘pig butchering’ works

• The victim and scammer meet on a dating app or dating website. Sometimes scammers will befriend the victim on social media.

• After some initial messages, the scammer will ask the victim to move the conversation to a free, encrypted messaging platform, such as Google Hangouts, WeChat, Line or WhatsApp.

• The scammer typically spends a couple of weeks developing a close relationship with the victim. This is sometimes referred to as ‘love bombing’ where the scammer is in contact with the victim several times a day professing their feelings for them.

• After a while, the scammer begins to talk about making money through different investments, most commonly involving cryptocurrency.

• The scammer will then offer to show the victim how to invest and will pressure the victim into transferring a small amount of money to see how easy it is.

• Initially, it often appears to victims as though they are making a profit from their investment. They may even be able to move money around, as the scammer entices them to keep investing more money.

• Often victims will be told they have to ‘top up’ their account to access their money or that they must always have a certain amount in their account otherwise it will be frozen, and their money lost.

• The scam ends when the victim has no more money to give or refuses to keep investing. At this point, the scammer may either disappear and stop all contact with the victim or may demand that the victim invests more money to access the money already invested.

• The victim is left with a significant financial loss while also losing the person who they thought they were developing a relationship with.

Source: ACCC

Originally published as Undercover footage shows how ‘pig butchering’ romance scam takes unsuspecting victims’ money