US climate scientists predict 2023 could be the Earth’s hottest year on record

Australia’s winter has been so mild one weather site suggested it ‘had taken the day off’, but other parts of the planet are cooking. See what it means for you.

Environment

Don't miss out on the headlines from Environment. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Like a child having a sook after a heavy tantrum, Australia’s weather has been having a quiet year.

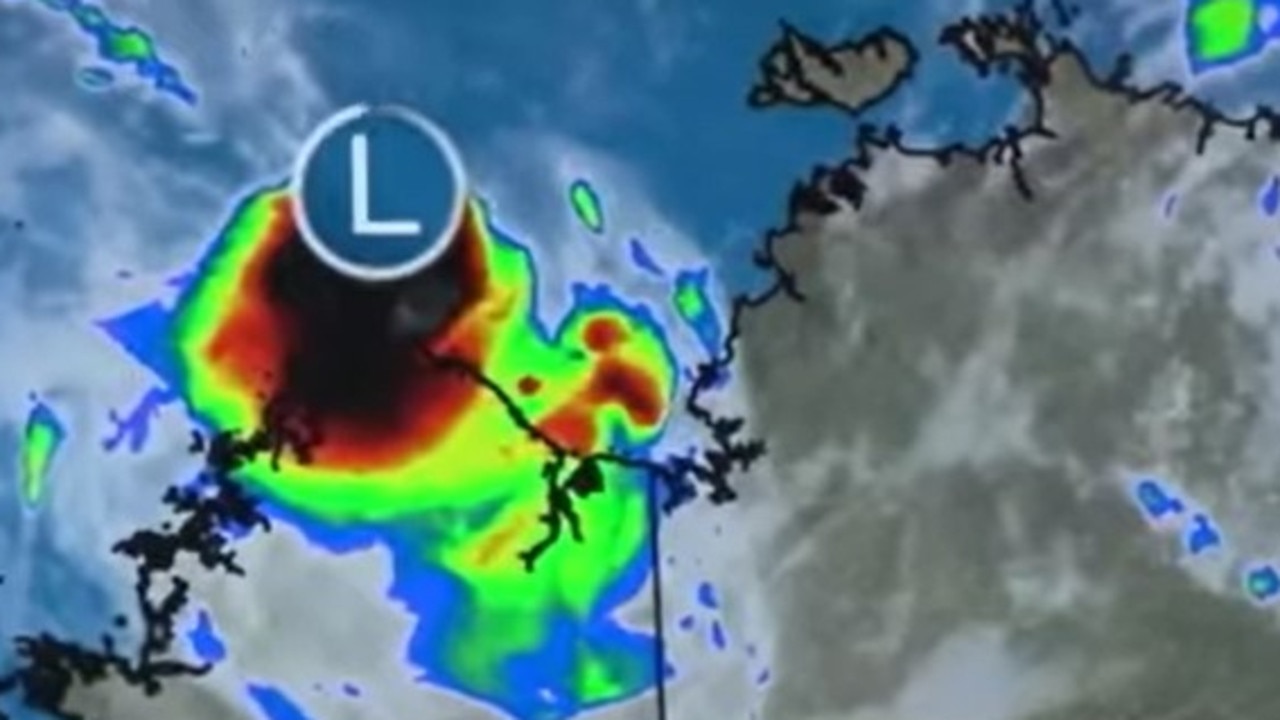

There have been highs and lows, of course – Queensland had its warmest June on record, and Western Australia had its lowest average rainfall in May – but the never-ending extremes of 2022 seem to have dissipated.

Thanks to a weakening La Nina, followed by a mild winter, Australia’s climate has been relatively unremarkable in 2023.

There was so little action on the national radar earlier this week, the weatherzone.com.au website quipped that Australia’s weather had “chuck(ed) a Tuesday sickie”.

“It’s almost as if the weather has taken the day off,” the site observed.

Meanwhile, other parts of the planet are absolutely cooking.

On July 7, the average of temperatures logged at weather stations all around the world was 17.24 degrees celsius – higher than any day ever recorded. It led to the hottest week on record, and followed the Earth’s hottest-ever June, according to the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO).

The new records come amid increasing concern about Antarctic sea ice, which is currently growing as it always does at this time of the year, but massively less than normal. In fact it’s expanded less this year than has been recorded since the start of satellite observations: 17 per cent below average.

Ocean temperatures are also massively outside their normal range; according to oceanographer Associate Professor Jan Zika from the University of NSW, parts of the Pacific are currently 2.5-3°C warmer than average, while the Atlantic has been a toasty 23 degrees some days.

The head of WMO’s World Climate Research Department, Dr Michael Sparrow, said temperatures in the North Atlantic were “unprecedented” and “much higher than anything the models predicted”.

And there are concerns those temperatures will push even higher, if (as most meteorological organisations predict) an El Nino system forms and strengthens in the Pacific.

“We are in uncharted territory and we can expect more records to fall as El Niño develops further, and these impacts will extend into 2024,” said Professor Christopher Hewitt, WMO director of climate services.

Prof Hewitt called it “worrying news for the planet” while UN Secretary-General António Guterres went even further, warning: “We are moving into a catastrophic situation”.

Climate scientists in the US are already predicting 2023 could be the Earth’s hottest year on record, as the first El Nino system the world has seen since 2016 turbocharges the underlying global warming trend.

It’s a bold claim for the scientists to make, given it’s only July and they could have egg on their face by December, but according to Sky News Weather meteorologist Alison Osborne, a record-breaking year is definitely a possibility.

“Our hottest year ever was 2016 and that coincided with an El Nino,” she said. “In 2022 we were still in La Nina and yet we had three weather stations crack 50°C in the northwest of WA.

A strong El Nino can definitely drive up that global average temperature, so I wouldn’t say that [a record-breaking year] is far fetched.”

Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology has not called an El Nino event as yet – their criteria are tougher than the overseas agencies who say it’s definitely happening – but many are concerned about what hotter and drier conditions will mean.

The prospect of a bad season for bushfires is very real, with NSW Rural Fire Service spokesman Inspector Ben Shepherd telling the Bush Summit this week the agency was seriously behind schedule in terms of hazard reduction burns.

Great Barrier Reef campaigners are also worried about a long hot summer.

“The declaration of an El Niño weather event is deeply concerning for the health of our Great Barrier Reef as it means hotter, drier conditions, which increase the chances of marine heatwaves and coral bleaching,” said the Australian Marine Conservation Society’s chief campaigner for the reef, Dr Lissa Schindler.

UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee is set to debate the state of the reef at its next session, to be held in Saudi Arabia in September.

The worsening environmental outlook comes as western leaders display a renewed sense of vigour in their attempts to grapple with climate change.

Just this week, US President Joe Biden and US Climate Envoy John Kerry met with King Charles and British finance groups at Windsor Castle to discuss investment in clean-energy solutions, and Germany’s Chancellor Olaf Scholz formally invited Australia’s Prime Minister Anthony Albanese to join the German-led “Climate Club”.

While some interpreted the invitation as a sign that Australia had finally thrown off its reputation as an international emissions laggard, Climate Council research director Dr Simon Bradshaw said it would actually lead to even greater scrutiny on Canberra’s climate policies.

“The fact is Australia’s emissions reduction target remains weaker than Europe’s, the US, and other members of the Climate Club. We will now rightly see even more international pressure on Australia to up our game,” Dr Bradshaw said.

The Climate Change Authority is currently considering what Australia’s emissions target should be for the year 2035; a recent consultation process on the question drew some 300 responses.

The target figure they eventually settle on will be the product of many factors – but there is always the possibility that record-breaking temperatures – the proverbial blowtorch to the belly – could add urgency to government thinking.

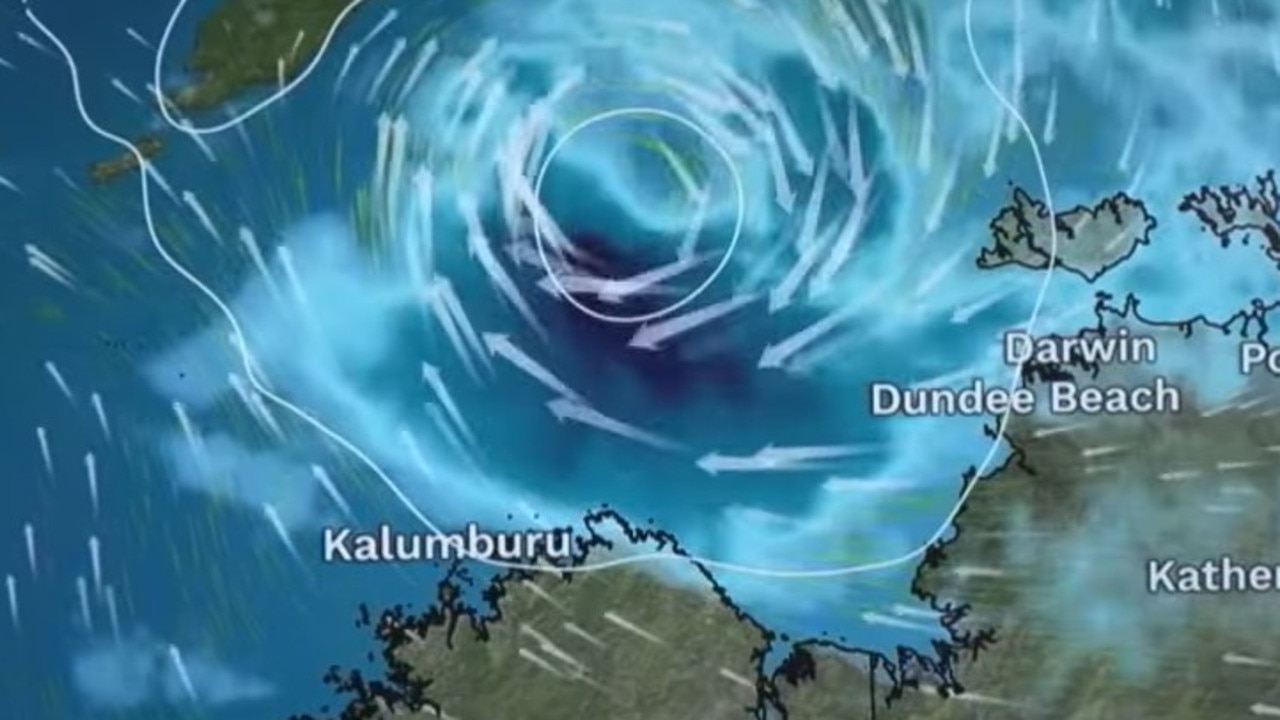

And according to Assoc Prof Zika, we should expect “a very dry summer ahead”.

“It looks like we’re going to have a double whammy in terms of the drought influence,” he said, with an incipient El Nino off our east coast, and another strong climate driver, the Indian Ocean Dipole, currently in a positive phase in the west.

“If those two modes of variation, the El Nino and the Indian Ocean Dipole are both in a phase that causes dry weather in Australia, then we’re in for a rough ride,” he said.

More Coverage

Originally published as US climate scientists predict 2023 could be the Earth’s hottest year on record