Opposition warns safeguard mechanism will lead to higher prices, introduction of carbon tax

The Opposition has blasted a deal between the government and the Greens over the safeguard mechanism. See why they’re warning of higher prices.

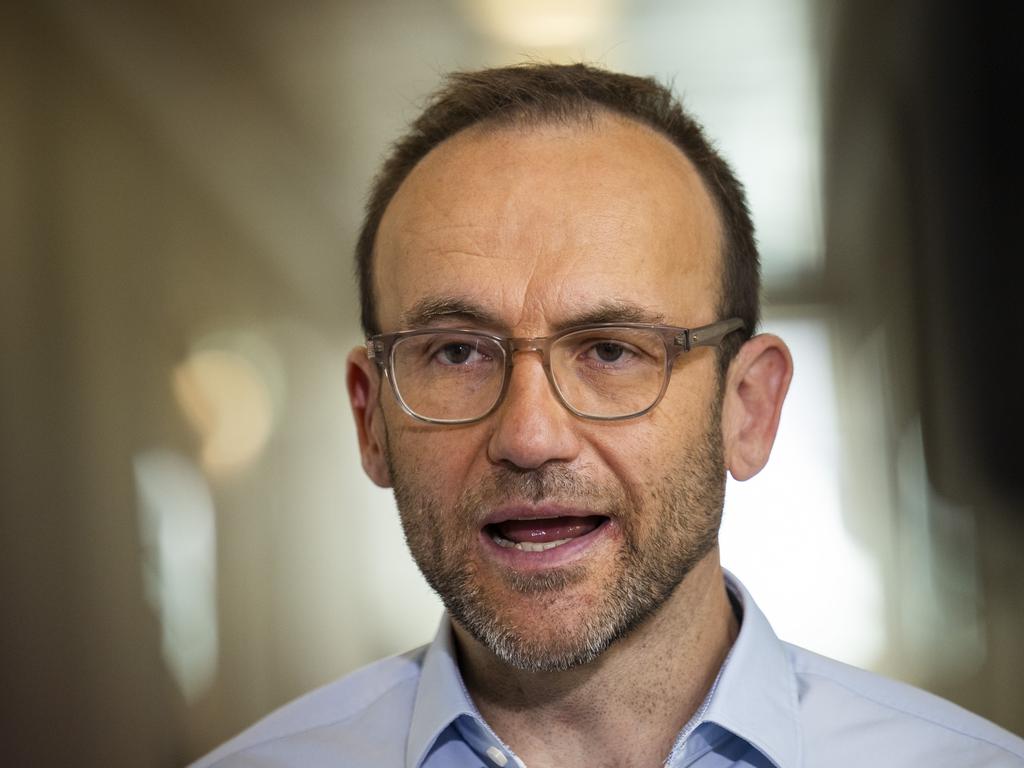

Opposition climate and energy spokesperson Ted O’Brien has blasted the deal between the government and the Greens over the safeguard mechanism, calling it a “plan to de-industrialise the economy” that will lead to higher prices for consumers.

“This plan is bad for the economy and it’s bad for the environment. It will make Australia’s economy weaker and the Australian people poorer,” he said.

“People will be seeing high prices because of the plan announced today.”

Mr O’Brien said the safeguard mechanism was “a Trojan horse” for “the most putative carbon tax in the world, bar none”.

The legislation would force Australian businesses to close and sets the country up “for an even worse energy crisis in years to come,” he said.

His warnings came after Labor and the Greens announced a deal on Monday morning that should see the Safeguard Mechanism pass through parliament this week.

Under the deal, key gas projects will need to have their emissions offset from day one - a clause that could make many of them unviable.

Here’s everything you need to know about the legislation and how it could affect you.

Why is parliament debating the ‘safeguard mechanism’ and what is it?

The “safeguard mechanism” was first proposed by the Abbott Liberal government in 2014, as a means to ensure Australia’s biggest greenhouse gas emitters did not go over certain pollution baselines. But the measure lacked teeth; since it was introduced in 2016, emissions have actually increased. Labor wants to introduce a new arrangement whereby the emissions baselines will come down by 4.9 per cent each year between 2023 and 2030 – meaning polluters will have to continually develop new processes to reduce their emissions, or else buy carbon offsets if they fail to do so.

So what deal did the government and the Greens come to?

The Greens wanted the government to ban all new coal and gas projects as a condition of their support for the Safeguard Mechanism legilsation. They didn't get that, but they did get stringent new emissions controls for new coal and gas projects, effectively meaning that some will no longer go ahead.

Under the plan, all new gas projects will need to offset their greenhouse gas emissions from day one of operation, including the controversial Beetaloo project.

The deal also ensures total emissions under the Safeguard Mechanism will be capped - meaning no new or expanded project can blow out the national tally.

Climate Council CEO Amanda McKenzie welcomed the deal, saying it would genuinely cut Australia’s emissions.

“Today’s agreement is a massive wake up call to any board or business execuitve that can keep stalling genuine climate action. The era of climate gridlock in Australia is over and the only viable path for any business is genuine, deep cuts to carbon pollution this decade,” she said.

Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen said “constructive discussions” with the Greens and the crossbench had resulted in a “strengthened design” to the Safeguard Mechanism.

Greens leader Adam Bandt claimed the deal was a massive win for his party.

“In balance of power, the Greens have stopped many of the 116 coal and gas projects in the pipeline from proceeeding, and now we’re coming after the rest,” he tweeted.

Voters who want climate action should “have a spring in their step,” he said.

“It shows we can take on the coal and gas corporations and win.”

Was the deal a surprise?

In some ways, yes. Mr Bowen had said last week it would be “irresponsible to just put a blanket ban on gas” as it was “an important firming and peaking backup to renewable energy”.

But there was strong public support for compromise; according to a uComms poll commissioned by Get Up!, 61.6 per cent of voters wanted the Albanese Government to work with the Greens and independents on the legislation.

Groups such as Greenpeace and the Australian Conservation Foundation welcomed the deal.

The Carbon Market Institute said it was a “stepping stone for progress ... but it must scale over time to ensure it continues to drive the transition of Australia’s industrial sector and broader economy”.

How many new coal and gas projects are we talking about?

According to the Australia Institute, there are 116 new fossil fuel projects awaiting Federal Government approval, and according to their calculations, if they were all green-lit, their global emissions would tally 4.8 billion tonnes – dwarfing the 205 million tonnes saved under the safeguard mechanism.

Will the safeguard mechanism increase prices?

According to Liberal leader Peter Dutton, yes. Businesses will have to invest more to reduce their emissions, or buy carbon credits – and either way, those costs will be passed on to the consumer, he has said.

The Business Council of Australia, which supports the government’s plan, has been a bit more circumspect, with CEO Jennifer Westacott telling a Senate committee the “fate of the Safeguard Mechanism has flow on consequences for the entire economy”.

Clean Energy Finance director Tim Buckley said any price increases arising from the safeguard mechanism would be “immaterial”.

“The impact of the safeguard mechanism on the Australian consumer is almost immaterial in terms of the overall impact of energy prices and the resulting wider inflation,” he said.

Extreme weather events had a much greater impact on an Australian business’s bottom line than any costs they would incur under the safeguard mechanism legislation, Mr Buckley said, citing the $8.5 billion in losses caused by flooding in 2022 alone as an example.

So what sorts of costs could go up as a result of the safeguard mechanism, and when?

Unless you buy your coal or iron ore by the ton, rest easy. The safeguard mechanism does not cover agricultural enterprises, transport, services or light manufacturing, so it’s not as though these everyday things will suddenly shoot up in price.

But as the Productivity Commission recently noted in its five-yearly productivity inquiry, abatement measures “increase the direct costs of production” and we can expect those costs to be passed on to the consumer.

But they also noted that “higher production costs can be viewed as the price of reducing the chance of even greater climate-related productivity costs in the future”. In other words: some higher costs now could prevent even higher costs down the track.

When those costs are incurred by big businesses (and then passed on to consumers) will vary from industry to industry, though it should be noted most facilities have already started the work of trying to reduce their emissions.

Interestingly, the Productivity Commission has called for the Safeguard Mechanism to be expanded into other sectors, including liquid fuel wholesalers, when the policy settings for the legislation are reviewed in 2026-27. That would certainly have a cost impact on motorists, but it should be stressed that’s a proposal only at this stage.

Who will the safeguard mechanism apply to?

The mechanism applies to 215 of Australia’s biggest emitting facilities – things like coal mines, natural gas plants, and heavy industrial factories.

Climate and Energy Minister Chris Bowen says if enacted, the changes to the safeguard mechanism will reduce Australia’s total emissions by 205 million tonnes – “the equivalent of taking two thirds of the cars off Australia’s roads”.

Why was the bill controversial?

The Coalition opposed the legislation, saying it will effectively act as a carbon tax, although others dispute this wording because the measure will not raise revenue for the government. The Coalition has also demanded the government release modelling to show how the changes to the mechanism will impact on everyday Australians; the government has so far refused to do so.

“If this policy is anywhere near as transformative as Labor claims, the government cannot justify hiding it from the Australian people, when it’s everyday households that will ultimately pick up the bill,” said the shadow climate and energy spokesperson, Ted O’Brien.

“Amidst a full-blown cost-of-living crisis, Labor wants to introduce a carbon tax and then hide modelling of its impact from those who’ll be forced to pay more for everything from fuel to food, and everyday materials.”

What would have happened if parliament rejects the safeguard mechanism bill?

Mr Bowen said without the safeguard mechanism, government projections show Australia will only reduce its emissions by 35 per cent by the end of the decade – substantially less than the 43 per cent target Australia promised to deliver at the COP27 climate conference in Egypt last year.

Why did the Greens demand an end to new coal and gas projects?

Because coal and gas are globally the biggest emitters of the greenhouse gases that cause climate change. The latest United Nations synthesis report on climate change revealed the world is on a trajectory to shoot past the 1.5-2.0° celsius of warming deemed acceptable under the Paris Agreement in 2015. We have already warmed the planet by nearly 1.1°, and even that amount has caused the climate to become completely unpredictable and destructive. The more the planet warms, the more unstable the climate becomes.

The Greens are not alone: climate scientists and even the International Energy Agency have called for an end to all new coal and gas projects globally.

Recent polling by uComms commissioned by the Australia Institute found differing levels of support for stopping new coal and gas projects. In the Queensland seat of Moreton, support was at 51 per cent, while in Bennelong (NSW) it was 53 per cent, Goldstein (Vic) it was 54 per cent, Mackellar (NSW) it was 60 per cent and Sydney (NSW) it was 65 per cent.

Are there other issues with the legislation?

Indeed there are. According to Emeritus Professor Ian Lowe, the legislation for the safeguard mechanism also radically underestimates Australia’s current and future methane emissions. While methane is the second most prevalent greenhouse gas, after carbon dioxide, it is up to 85 times more potent over the short term.

Prof Lowe said the International Energy Agency’s calculations about Australia’s carbon dioxide emissions were the same as the government’s, but when it comes to methane, the IEA’s figures are 63 per cent higher than the government’s figures.

“The IEA is no ratbag environmental group; it’s the voice of the energy industries at the global level,” he said.

“If the IEA figures are right, and they have no reason to exaggerate, the task [of reducing our emissions] is much greater,” Prof Lowe said.

What happens next?

The legislation is expected to pass both houses of parliament this week. The changes will come into effect on July 1.

More Coverage

Originally published as Opposition warns safeguard mechanism will lead to higher prices, introduction of carbon tax

Read related topics:Explainers