NOW that Kyle Chalmers has won gold in the 100m freestyle, legend status is guaranteed. As Mike Colman explains, the “hundred” is THE event in the pool.

“It doesn’t matter what pool, or what meet,” he says. “It’s a pretty nice feeling to know you’re the fastest swimmer in the place.”

It is pursuit of that feeling – and the swagger that comes with it – which makes “the hundred” Olympic swimming’s blue riband event, despite the reintroduction of the 50m freestyle in 1988.

Sure, the winner of the shorter race might theoretically be called the Top Gun of the meet, but the 50m will never have something that the 100m does: Tarzan.

Johnny Weissmuller, the original Tarzan of the movies, won the Olympic 100m freestyle twice, in 1924 and 1928. So did the legendary father of modern surfing, Duke Kahanamoku, who took gold in 1912 and 1920.

Add in the fact that the 100m freestyle was the final individual race that secured Mark Spitz an unprecedented seven gold medals in Munich in 1972, and it is not hard to see why the race holds such an exalted position in Olympic history.

Just as it is not hard to see why it means so much to Australians. The 1500m freestyle has long been known as “Australia’s race”, but with one gold and three silver medals since 2008 – and outstanding prospects for Rio – the 100m is threatening to take that mantle.

The US may have won the most 100m freestyle gold medals in both men’s and women’s events, but Australia is second.

With three golds, won by Jon Henricks in 1956, John Devitt in 1960 and Michael Wenden in 1968, Australia sits only behind the US with 13 in the men’s event, while the women’s medal ladder is closer.

The US women have won the event eight times with the second placed Australians having won five times, including the first-ever women’s title that went to Fanny Durack ahead of fellow Aussie Wilhelmina Wylie in Stockholm in 1912.

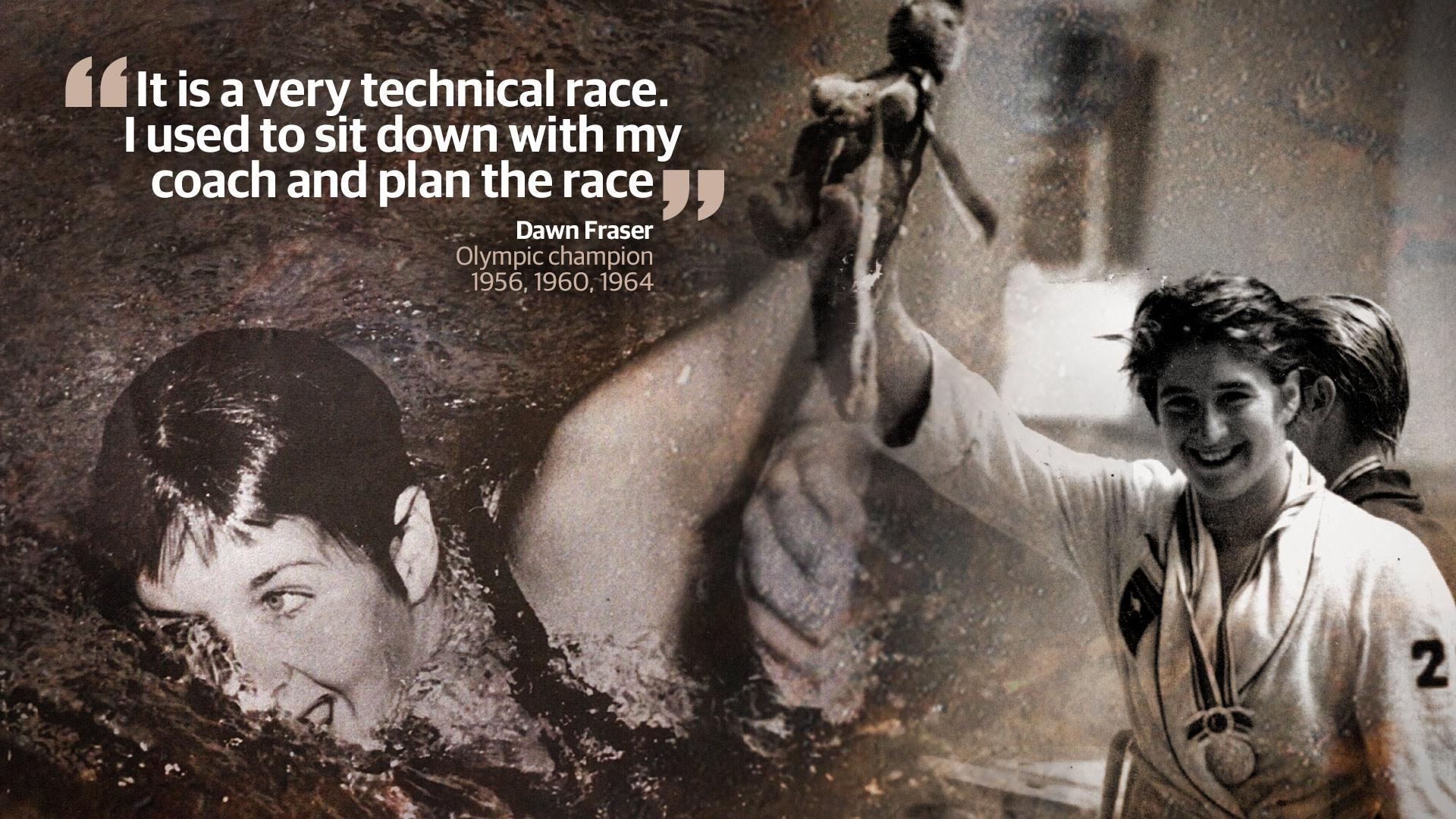

And in Dawn Fraser, Australians can boast something that no other country can – a swimmer with three consecutive 100m gold medals, between 1956 and 1964.

The last Australian to win Olympic gold over the distance was Jodie Henry in Athens in 2004, but our swimmers have come desperately close through Stockwell in 1984, Eamon Sullivan and Libby Trickett in 2008 and James Magnussen four years ago.

All of which makes this year’s event in Rio all the more exciting, with three Australians – Cam McEvoy and sisters Cate and Bronte Campbell – all considered excellent chances to put us back on the top step of the podium.

And should one – or even two – of them win gold, it will be the latest chapter in a fascinating story that has seen a full gamut of emotions, from triumph, to disappointment and even tragedy over the past century.

Australia’s first male medal in the 100m was silver to Cecil Healy in 1912. The Sydney lifesaver also won gold in the 4x200m freestyle relay and could very well have gone one better in the individual event.

Healy had finished first in his semi-final to make the final, but due to a mistake by American team management the three US swimmers, led by Duke Kahanamoku, did not show up for the semis and were not considered for the final.

Believing the final would not be a fair contest without Kahanamoku, Healy led a protest to officials and the Americans were allowed to swim their own qualifying race.

Kahanamoku duly made the final and took gold, beating Healy by just over a second. Six years later Lt Cecil Healy was killed in action at the Somme, becoming the only Australian Olympic gold medallist to die in World War I.

It would be 44 years before Australia won another Olympic medal in the 100m freestyle but in 1956 in Melbourne, we dominated the event like no other country since, when our swimmers repeated the feat of the USA in 1924 by finishing one-two-three in both men’s and women’s races.

“People ask if we felt any pressure because we were in our own country but going to the pool we were completely calm,” recalled John Devitt, who finished second behind Jon Henricks and ahead of countryman Gary Chapman in the men’s final.

“We all knew we were going to finish first, second and third. The only question was, which one of me and Gary was going to be second behind Jon?”

Given that Henricks had won 55 races from 56 starts over the distance in the previous three years, it was a fair assumption, although Devitt was pipped by only .4 of a second.

The next night the Australian women were also expected to score a clean sweep, but this time the question mark was over who would take gold, with Dawn Fraser and Lorraine Crapp the fiercest of rivals.

In the end, after the two teenagers had turned the second 50 metres into a race of two, Fraser got home by 0.3 of a second in world record time. Aussie Faith Leech was third.

It was the start of eight years of Fraser dominance and the ultimate justification for her love affair with the event.

‘I always liked the distance,” she said. “I loved the challenge. People assume that you just dive in and swim two laps as fast as you can and that’s it, it’s over, but it’s not like that.

“It is a very technical race. I used to sit down with my coach and plan the race. You had to look at the other swimmers and think, ‘where can I swim fast, where should I slow down?’

“The older I got the smarter I got. By the time I got to the third race, in Tokyo, I had learnt so much. In Rome in 1960 I was favourite. I hadn’t lost a race since Melbourne so that was fair enough, but in Tokyo I was at long odds.”

Seven months before the Tokyo Games Fraser had been driving her mother, sister and a friend home from a social event when her car skidded and hit a parked truck. Her mother was killed and Fraser spent six weeks with her neck in plaster because of chipped vertebrae.

“After the car accident not too many people gave me much of a chance,” she said. “Sharon Stouder, the American girl, was expected to win. She was younger, she hadn’t gone through what I’d gone through, so I had to be smart. I had to work out the perfect plan to beat her, and that’s what happened.”

Does she remember what that plan was?

“Of course, but I’m not telling you. It was between me and my coach. I don’t give away my secrets.”

John Devitt, who went one better than his silver in Melbourne by taking gold in Rome four years later, isn’t so reticent about his gold medal-winning game plan.

“There was a grate on the bottom of the pool in lane three, 10 metres out from the wall at the finish,” he said. “When I swam my semi-final I made sure I finished with a time that got me that lane.

“I wanted to be able to look down and know how far I had to swim so I could really hit the wall. I’d just missed out in Melbourne. I didn’t want it to happen again.”

The plan went perfectly – up to a point. When he saw the grate, Devitt threw everything into his final few strokes and hit the wall under the water with his right hand, just as American Lance Larson in the next lane appeared to do the same.

“An American coach came up and told Lance he had won, so I congratulated him and got out of the pool,” Devitt recalled. “Then when I got over to the Australians they told me I had won.”

And then started one of the greatest controversies in Olympic history.

While there was electronic timing, the placings were determined by human consensus. The three judges in charge of picking first place voted two to one in favour of Devitt, but those picking second place also voted two-one Devitt, meaning of the six judges, three felt Devitt had won, and three believed Larson was the winner.

The chief judge, Germany’s Hans Rumstromer awarded the race to Devitt.

The Americans protested, and the final appeal was not turned down until six years later.

“The funny thing was when I was working for Speedo later in my life I got friendly with a lot of those Americans coaches and officials,” Devitt said. “They used to say to me, ‘you know you didn’t win that race, don’t you?’ and I used to say, ‘Really? Do you want to see my gold medal?’”.

Four years later, the pool was ruled by Australian teenager Michael Wenden while at the following Games in Munich, 15 year-old Shane Gould’s five individual medals included bronze in the 100m freestyle.

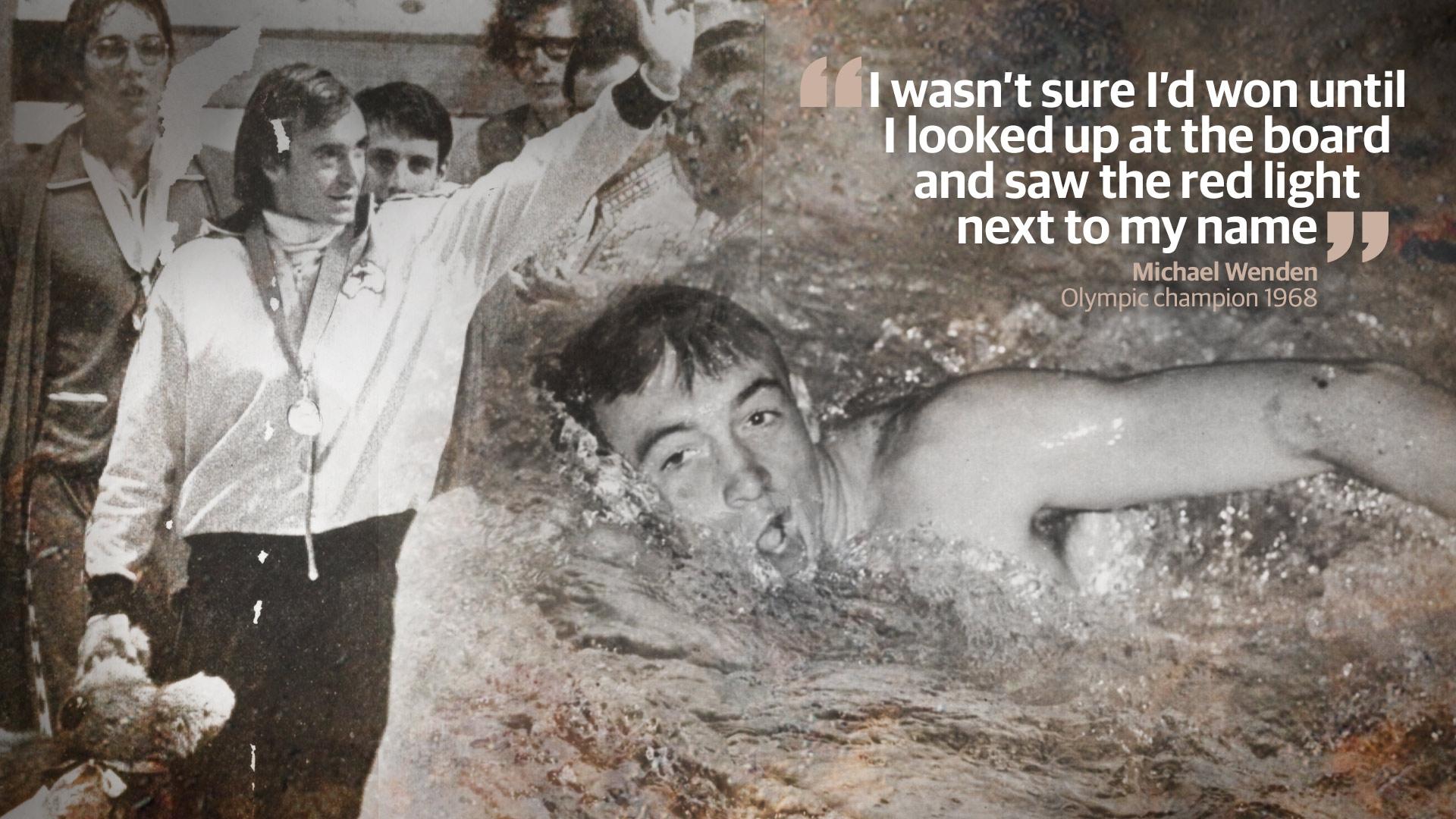

But it was 18 year-old Michael Wenden who, in Mexico in 1968, became Australia’s third and, so far, last winner of the event.

While it would be poetic to suggest winning Olympic swimming’s blue riband event had been a long-held dream for the Sydney youngster, in fact his ambition was less lofty.

“When I was 14 an older friend of mine took me around to his girlfriend’s house,” he said. “My recollection is that her brother had just been to the 1964 Olympics and finished eighth in the final of the backstroke. Everyone was so pleased; his family was making such a big fuss.

“I remember thinking how terrific it was. I thought, ‘wouldn’t it be great to go the Olympics and make the final?’ Two years later I went to the Commonwealth Games and won gold there, but my aim was still to make an Olympic final.”

Wenden had two major strokes of luck in the lead up to the 100m final. First was that the Australian Olympic Federation had been warned that the altitude in Mexico City could be damaging to the athletes’ health, so they took the unprecedented step of sending the Australian team to Mexico to acclimatise five weeks before the start of competition, giving Wenden a head start on his rivals.

“At first I thought I was going to die in the thin air, then my times started to come down dramatically.

“At one stage I thought, ‘I’m pretty sure I’m going to make the final’, then it became ‘wouldn’t it be nice to win a medal?’ On the last day of training I was looking at bronze and after we’d come third in the relay on the first day and I looked at everyone else’s splits I was thinking I could do better than bronze.”

Second stroke of luck for Wenden was the fact that his teammate Robert Windle, winner of the 1500m freestyle four years earlier, had just returned from a stint at the University of Indiana.

“I was fastest qualifier for the final and America’s Zac Zorn was second fastest. Bob came up to me before the race and told me that he had seen Zac in college competition in the US and I shouldn’t be surprised if I was looking at his feet after 25 metres.

“He said Zac had this amazing starting burst but he had a tendency to panic and go too hard. He told me not to worry if he was in front early, that he’d die towards the end.

“That’s exactly what happened. At one stage I was looking at Zac’s knees. If Bob hadn’t spoken to me I’m not sure how I would have reacted, but I stayed calm and from the turn I had the sense I was gaining on him with every stroke. Even so, I wasn’t sure I’d won until I looked up at the board and saw the red light next to my name. Zac finished last.”

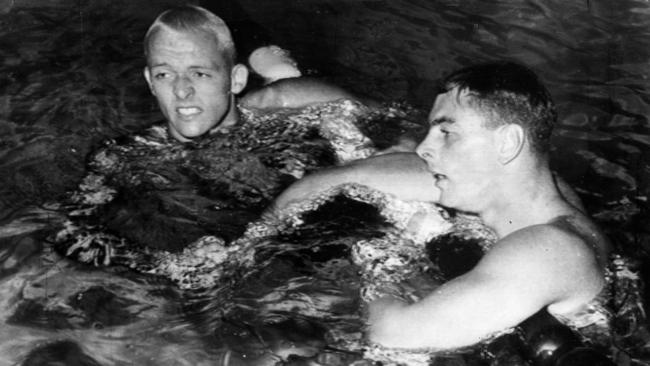

Windle also came to the rescue two days later when he finished sixth behind Wenden in the 200m freestyle final.

“Everything went black for the last few strokes,” Wenden said. “I was hanging onto the lane rope trying to regain my senses when I felt myself sinking. I remember thinking, ‘I’ve just won an Olympic gold medal and I’m going to drown. This will not look good’, but Bob was coming over to congratulate me. He realised what was happening and held my head above the water. That’s twice I owe him”.

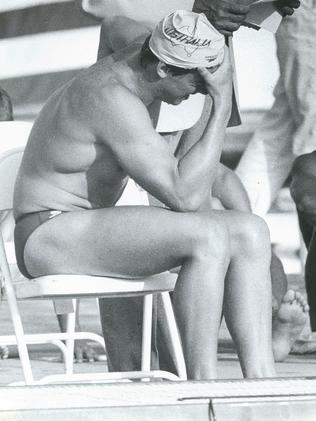

Four years later Wended headed to Munich to defend his title on a less than ideal preparation. He was now married and a father, a fulltime university student, and no longer with his long-time coach Vic Arneill. For some time he trained himself.

Even so, he very nearly played a major role in Olympic history.

Munich was the Olympics at which Mark Spitz set himself the goal of winning seven gold medals, but such was the mindset of the man that he would rather win one less gold that come home with a silver.

The 100m freestyle was the last individual race on Spitz’s list but with Wenden beating him in the semi-final and going into the final as fastest qualifier, the American started having second thoughts.

“Two American coaches told me independently that Spitz had wanted to pull out of the final and it took them five or six hours to talk him into swimming,” Wenden said.

It is now history that Spitz did swim, and Wenden finished fifth, leaving it up to another generation of Australian male sprinters to try, so far, unsuccessfully, to win the most coveted gold medal in Olympic swimming.

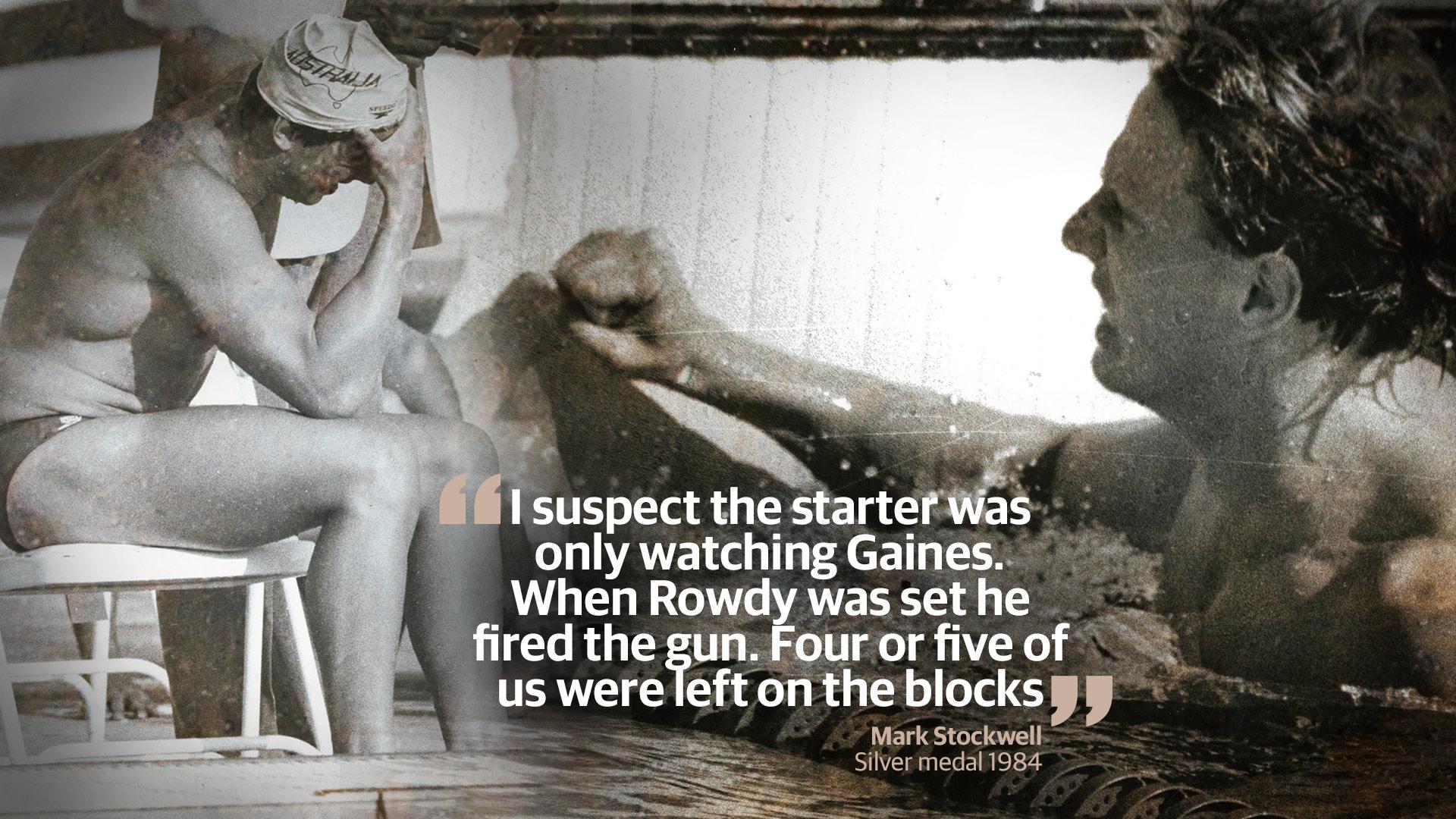

Without doubt the unluckiest has been Stockwell, who in 1984 in Los Angeles seemed destined to follow in the footsteps of Henricks, Devitt and Wenden, but was thwarted by a trigger-happy Panamanian starter and a canny American coach.

Stockwell went into the final as fastest qualifier, with his major rivals expected to be the two Americans Mike Heath and the veteran world record holder Rowdy Gaines.

Gaines had been robbed of the chance of gold when the US boycotted the Moscow Games four years earlier. Swimming the last individual race of his career, he was the crowd favourite and, thanks to his coach Richard Quick, the best prepared.

Quick had noticed that the race starter was Frank Silvestri whom the US team had protested against because of his fast starts at the 1983 Pan-American Games.

Two days before the Olympic final Quick took the gamble of changing Gaines’s starting style from the standard “grab start” in which the swimmers stand at the back of the blocks before stepping forward and hooking their toes over the edge, to the-then revolutionary one leg forward, one back crouched “track start”, in order to take advantage of Silvestri’s quick-draw technique.

It all worked perfectly for Gaines, who was in the air the moment the gun went off while Stockwell and the others were still getting into position.

“The rule is that you fire the gun when everyone is set,” Stockwell said. “I suspect the starter was only watching Gaines. When Rowdy was set he fired the gun. Four or five of us were left on the blocks.”

Stockwell took off after Gaines but could never make up the lead. He can be seen punching the water in frustration after the finish. He wasn’t the only one upset.

“It’s all there as a moment frozen in time,” he said. “I remember seeing our head coach Terry Buck with a horrified look on his face. Our manager Tom Brazier was visibly upset. He said, ‘do you want to appeal?’ and I said, ‘yes’ and Tom went off to lodge the appeal.

“It was crazy. We were in southern California; an American had won in a fairytale end to his career. The place was going nuts, and here was an Australian trying to rain on his parade. Then Mike Heath’s coach lodged an appeal as well because Mike had been left at the start too.

“Everyone was standing around arguing and then I remember this little guy with headphones and a clipboard running up and saying, ‘Everybody get out of the way, New York is coming out of an ad break’. We were pushed aside, the next race started and that was it. The Olympics moved on.”

It would be left to another Queenslander, Jodie Henry, to finally put Australian back onto the top step.

When Henry just missed out on making the team for the Sydney Olympics, she was approached by a ex-swimmer who patted her on the back and said, “better luck next time”. It was Dawn Fraser. Their paths have not crossed since, but the former champion’s words proved prescient.

By the time Athens came around in 2004 Henry was very much in the team but not the Australian woman expected to win the 100m freestyle. That weight was being carried on the shoulders of Libby Lenton, the world record holder.

It proved to be a burden too great and Lenton failed to make the final. Henry on the other hand, thrived, breaking Lenton’s record in her semi-final and stamping herself as the greatest danger to defending champion, Dutchwoman Inge de Bruijn.

As they stood behind the blocks for the final, the 30 year-old de Bruijn stared at the Australian 10 years her junior in an attempt to psyche her out. Henry, typically, just laughed.

“I couldn’t believe she would think I was a threat,” she said.

Less than a minute later Henry was to prove more than just a threat. She was the new Olympic champion, although at the time it seemed she was more interested in getting home to be with her pet budgie than strutting around the pool-deck like the stereotypical hot-shot sprinter.

“It wasn’t so much that I was over it, more that it had been such a big week,” she said. “It’s really crazy and you don’t get the chance to sit back and enjoy it. I just wanted to get home so I could think about things.

“It’s now that I look back that I realise what an amazing time it was. When I think about how many Australians have tried to win that race and how few of us there are who have done it, it makes it even more special.”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

TikTok star is golf’s secret weapon

Min Woo Lee opens up about balancing tradition with social media fame as he reflects on his high-profile friendships and making his mark in style.

Watch: NTFL battlers prepare for rare opportunity

Wins are at a premium for these two NT clubs Buffaloes – and a big Friday night clash could spell the end of one side’s season. Find out how to watch the match LIVE and FREE.