It has become one of the most iconic examples of Sunshine State passion. Billy Moore walking out of the tunnel in 1995 screaming “QUEENSLANDER” again and again. But the origin of that spine-tingling war cry goes back to a team meeting in 1987, where Paul Vautin convinced master coach Wayne Bennett that he knew what would get his teammates fired up to bring down the Blues, writes Mike Colman.

THE OXFORD ENGLISH DICTIONARY reckons it’s a word.

“Queenslander,” it says.

“Noun. A native or inhabitant of the Australian state of Queensland.”

Whoever wrote that has obviously never been to Suncorp Stadium on Origin night.

Forget the fact that just being an “inhabitant” of Queensland does not a true Queenslander make.

Everyone knows you have to be born here, preferably with second-generation maroon bloodlines on both sides.

Forget, too, that describing it simply as a “noun” falls about as short as Noel Cleal’s drop-out in the wet at the SCG, Game 2, 1984.

And as for the dictionary’s guide to pronunciation: “kwi:nslanda”, oh pur-lease. Where’s the passion, the emotion? The growl that is dragged up from the gut and leaps from the back of the throat like a red cattle dog off the tray of a ute?

Kerweeeeeeenssssslannnndarrrrrrrrr …

The fact of the matter is that what “Queenslander” means to … well, Queenslanders, can’t be encapsulated in a few words. And it should never be attempted by outsiders.

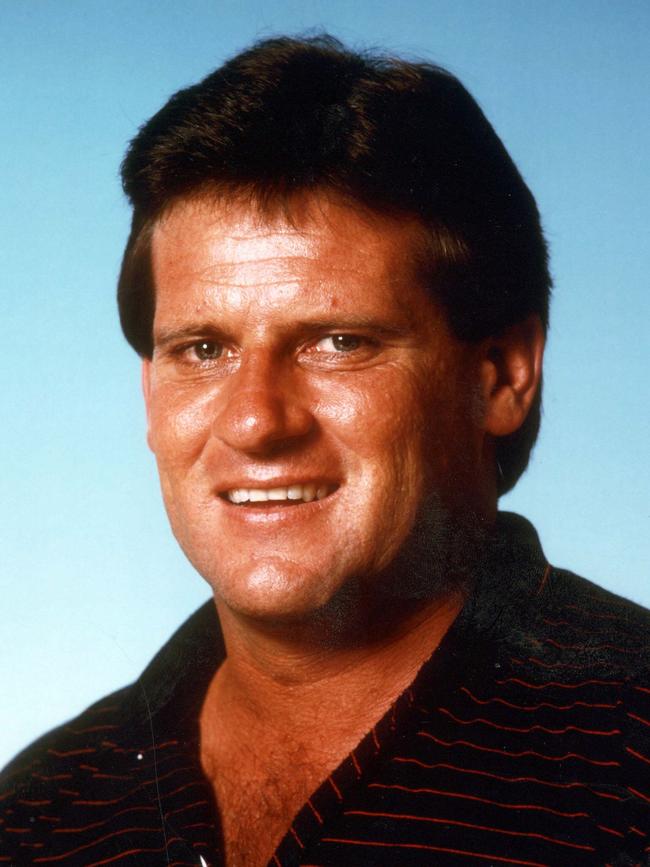

“It says something about you, about your upbringing, your parents, where you went to school, who you are,” says former Origin player and coach Paul “Fatty” Vautin – and he should know. He gave birth to it.

OK, so he didn’t actually coin the word. It has been around since June 6, 1859, when Queensland officially broke away from New South Wales, thus setting in motion a slow-building avalanche of cross-border animosity that would result in the first State of Origin match 121 years later.

Between 1866 and 1939, The Queenslander was a weekly news and literary magazine published by the Brisbane Newspaper Company, and in 1970, after a rare one-point rugby league win for the home team over the old enemy from south of the Tweed, radio caller Kev Kelly famously remarked: “They’ve done it … they’ve humbled the Blues and I tell you what, it’s great to be a Queenslander.”

So to say Fatty was the originator of the term “Queenslander” is laying it on a bit thick. What he did was rejuvenate it: pick it up, brush it off and give it new relevance.

THE BIRTH OF A LEGEND

IT HAPPENED IN A BACK ROOM OF SYDNEY’S NOW DEFUNCT Rushcutters Bay Travelodge hotel before the second game of the 1987 Origin series.

It’s fair to say things weren’t looking too good for the mighty Maroons that day as coach Wayne Bennett gathered the boys around.

The man, now regarded as arguably the greatest rugby league coach of all time, had been in charge of the Queensland team for four games – and they hadn’t won one of them.

One series down and one loss away from a second, careers were on the line.

“Basically Wayne just told us that it was our last chance,” recalled former Maroons fullback Gary Belcher.

“He said if we lost again a lot of us weren’t going to be around anymore. The senior blokes like Wally (Lewis) and Mal (Meninga) and Geno (Gene Miles) and Fatty would be OK but it was pretty obvious that Wayne and the newer ones like me would be gone. I’d played three games and I hadn’t been on a winning side once.

“That’s where the ‘Queenslander’ call came from. Wayne said we should come up with something that would pull us together and give us a lift when we were down. People said it was me that came up with it because I was the one calling it out the most at first, but that was only because I was the one at the back and could see when we needed it. Also, often times I was the only one who had enough breath to call it. Fatty was the one who came up with it.”

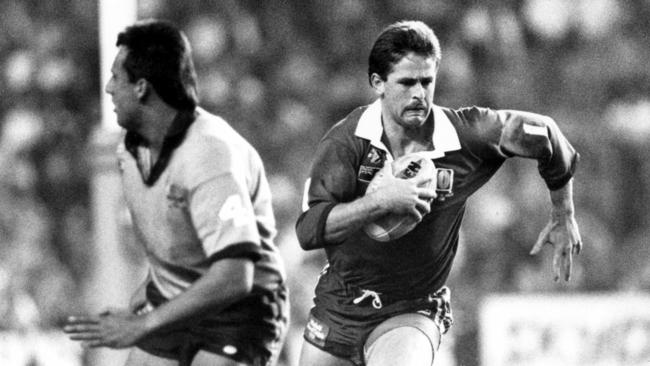

Born and bred in Brisbane, Vautin had moved to Sydney in 1979 aged 19 to play for the Manly-Warringah Sea Eagles. When he got the call-up for the first of his 22 matches for the Maroons in 1982, Vautin was the personification of what Origin was all about.

When league great Arthur Beetson had led the Maroons out for the inaugural Origin match two years earlier, it was the first – and only – time he would play for his home state.

Having headed to Sydney in 1966 to play for first Balmain, then Easts and Parramatta, his previous 17 interstate matches had all been in the blue of NSW.

Origin changed all that, giving Queenslanders based interstate, in New Zealand or, in the notable case of Allan Langer, England, the chance to return home to take on the Blues.

Vautin would stay in NSW longer than most, but never for a moment did he forget where he had come from. Along with his Manly teammate and fellow Maroon, Chris “Choppy” Close, it was as if he was working as an undercover agent in enemy territory, just biding his time for the chance to put the Blues to the sword each season.

As the Maroons’ revered team manager Dick “Tosser” Turner once put it, “I would never say that one player was any prouder than any other to play for the team, but to me Paul epitomised that pride”.

Vautin had heard Kev Kelly’s “It’s great to be a Queenslander” call as a 12-year-old listening to the radio, and was known to recite it happily to teammates at Maroons training.

Prior to the 1986 series, for which he was sidelined with a broken arm, he was interviewed on a TV show about the so-called “Queensland spirit” – much maligned by NSW critics such as Origin commentator Jack Gibson.

“People like Gibson can say it doesn’t exist all they like,” Vautin told the interviewer.

“They just don’t get it and they never will. How could they? They’re not Queenslanders.”

Little wonder then, that when Bennett asked for suggestions for a Maroons rallying cry, that one word – “Queenslander” – jumped to mind.

“All these suggestions were being thrown around,” Vautin recalls.

“Red zone, red alert, oranges, apples … I reckon we went through every fruit in the shop, and it just came to me. I said, what about we just call out ‘Queenslander’, and that was it. It was right. It was gold. Basically it was a call to arms. It was saying, ‘we’re locking our arms and holding the line together. We’re building a Queensland wall, and no one gets through’.”

FLICKING THE SWITCH

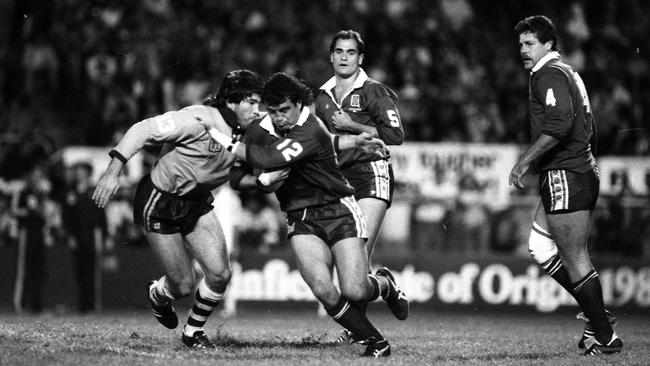

THE NOW-FAMOUS QUEENSLAND RALLYING CRY GOT ITS FIRST airing early in the second half of that game.

It was probably Belcher who called it.

As he says, he could see what was needed from the back of the field, and at 6-nil down with the series slipping away, anything was worth a try.

It was like flicking a switch, Vautin says.

Sparked by Belcher’s call, others in the team joined in.

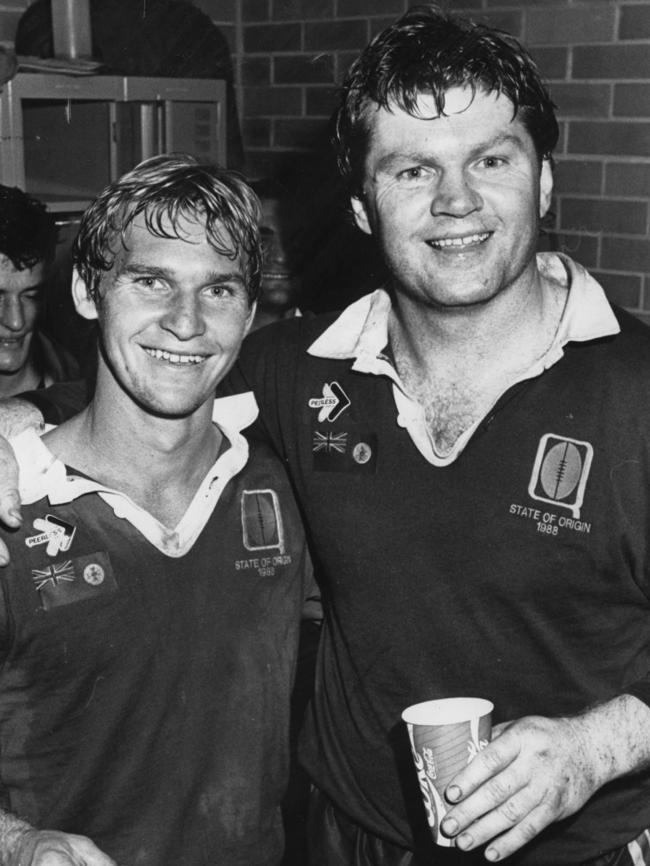

The Maroons were galvanised and invigorated. They scored three tries and won 12-6 to square the series, but it was at Lang Park in the decider a month later that the Queenslander call entered Origin folklore.

The Maroons came in at half time leading 10-8. Bennett addressed a few issues, Queensland captain Wally Lewis had his say and then handed over to his vice-captain, Vautin, for a final word before they returned to the field.

“I know this sounds simple,” Vautin said. “But if they don’t score, we win.”

The Queenslander call went up, over and over for the next 40 minutes.

So often, and so loud, that it was heard by the crowd, picked up by the TV microphones and transmitted into the press box.

The next morning’s newspapers were full of it – along with the final score: Queensland 10-8.

“The NSW players had a bit to say about it,” Vautin says.

“They scoffed. They didn’t understand it, they still don’t, but it was palpable. It was real. It lifted us time after time. We won three series in a row from there so we didn’t use it as much after a while, and in time it drifted away but it was always there if we needed it.”

In 1995, at the height of the Super League War, it was needed more than ever.

When Maroons coach Bennett was told he couldn’t select his Super League players he resigned his post, forcing the Queensland Rugby League to make one of the bravest, and ultimately inspired, choices in the game’s history.

They offered the job to Vautin.

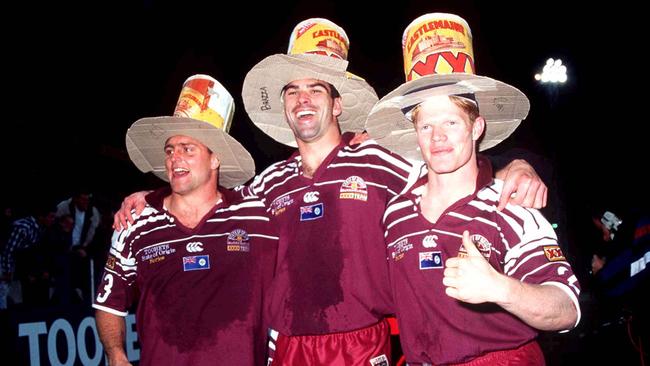

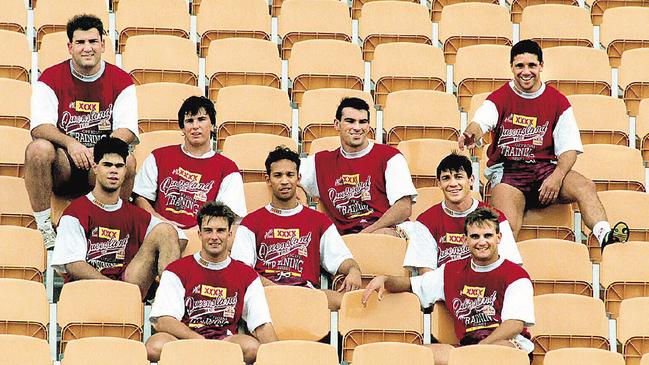

With next to no coaching experience and few players deemed to be of Origin standard to choose from, Vautin pulled together a ragtag army of “Neville Nobodies” and enlisted three old friends as support: Tosser Turner, Choppy Close … and the Queenslander call.

“At the first meeting I got up and spilled my guts on what being a Queenslander meant to me, and at the end I said, ‘Oh, and by the way, the Queenslander call is back. It’s yours. When you need that unstoppable force, when you can’t let them through, you reach for it. It’ll be there’.”

Listening that day, his eyes like saucers, was North Sydney Bears backrower Billy Moore.

By his own admission he was not the most naturally gifted of players, and at 90kg certainly not the largest. But what Moore lacked in skills and bulk he made up for in heart and intensity.

If ever there was a player born to take the Queenslander call from Vautin’s hands and carry it into its second incantation, Billy Moore was it.

“I grew up in Wallangarra, 50 metres on the Queensland side of the border. When I woke up in the morning I could look out the window and see New South Wales. Everything, daylight saving, the yellow numberplates, it was all there, very real. I felt like I was on the coalface of the frontier, keeping the Blues out of Queensland,” he says.

When he was nine years old, Moore saw the meaning of Origin reflected in the eye of his father Ron.

“My dad was a classic country guy, a labourer all his life. He’d never leave town. I played 211 first-grade games for North Sydney, 17 Origins and three Tests for Australia and he never saw one of them. One time the Bears offered to send a limo to pick him up and bring him to Lang Park to watch me play but he said no. He wanted to watch it on his TV sitting in his chair at Wallangarra, that’s just how he was.

“In 1980 I was lying on the loungeroom floor watching the first-ever Origin on TV. Dad was sitting in his chair and when Artie Beetson led Queensland on to the field I looked up and Dad had a tear in his eye. I couldn’t believe it, my head snapped back. That was the first and only time I’d ever seen him show emotion. It showed me how much Origin meant. After that I told my mum and dad that I was going to play Origin. I was nine years old. When I was 15, I started training for it.”

THE SPIRIT OF QUEENSLAND

MOORE’S FIRST ORIGIN WAS GAME 2, 1992. HIS ROOM-MATE was Peter Jackson, who would earn Maroons legend status for his 100 per cent devotion to the cause both on and off the field.

“The first day I was standing at my bed looking down at my Queensland tracksuit and Jacko came up behind me and said, ‘Welcome to the Queensland family … now go out there on Wednesday night and prove you deserve to be here’.

“Jacko told me the three things that meant being a Queenslander to him: One, help your mates; two, find an answer; and three, no excuses. When he said that to me I was so pumped I said, ‘Let’s go training.’

“He said, ‘Training? We don’t go training. We go out for a drink’. That was my introduction to the Maroons family.”

By the time Moore received the call to join Fatty’s Nevilles, leading to what he says were the best six weeks of his life, he was a veteran of eight Origin matches.

A solid, wholehearted player who gave it everything he had from kick-off to fulltime, he would never be remembered on a par with Maroons greats such as Lewis, Meninga, Langer, Lockyer, Thurston or Smith.

In fact, if not for a few brief moments of fortuitous timing in Game 1 1995, he might not have been remembered at all.

With Super League players barred from the 1995 Origin series and the star-studded NSW side featuring the likes of Brad Fittler, Andrew Johns and Paul Harragon expected to easily brush aside the seemingly undergunned Maroons, Channel 9 feared their biggest ratings winner might lay an egg.

To make the coverage more attractive, the network’s head of sport, Gary Burns, brought in some innovations that might seem commonplace now, but back then were cutting-edge, such as fixed cameras in the team dressing rooms and having a cameraman walk backwards filming the players as they headed back on to the field after halftime.

The opening game was at the Sydney Football Stadium. When the players trooped into the sheds at the break the scenario was almost identical to the one eight years earlier when the Queensland call had first made its mark: Queensland up 2-0 … “If they don’t score, we win”.

After coach Vautin had spoken to the players, Maroons second-rower Gary Larson sidled up to Moore.

A teammate at North Sydney, Larson was another tackling machine. So effective were the pair in tandem that the press nicknamed them Batman and Robin – Queensland’s Dynamic Duo.

Larson was every bit as passionate as Moore but an elbow to the throat that had permanently affected his voice meant he left the stirring speeches to his backrow partner.

Nodding towards the inexperienced youngsters in the team he rasped roughly into Moore’s ear, “Better give ’em some of that Queenslander stuff, Billy”.

Moore didn’t need to be asked twice.

He told them what Peter Jackson had told him before his first match, and then launched into a full-blooded Queenslander call.

Within seconds they were all doing it, the one-word anthem reverberating off the walls until Choppy Close opened the door and motioned them out into the passageway where the cameraman was waiting.

“We had no idea the camera was there,” Moore says.

“No one had warned us. I didn’t even see it.”

But the camera saw Billy.

First out was Queensland captain Trevor Gillmeister, followed by Mark Coyne and Gavin Allen, then a short break before Moore, his eyes focused straight ahead, strode down the tunnel, arms swinging menacingly by his sides like a wrestler eager to enter the ring.

He was a few paces away from the camera, perfectly framed on millions of TV screens around the country when he let it rip.

Kerweeeeeeenssssslannnndarrrrrrrrr …..

Then another immediately afterwards.

Kerweeeeeeenssssslannnndarrrrrrrrr …..

And then a third, this time when he had passed the cameraman and could be heard only as a disembodied voice in the distance, making the whole thing seem bizarre yet all the more powerful and heartfelt.

Kerweeeeeeenssssslannnndarrrrrrrrr …..

As commentator Ray Warren noted in classic understatement, “Billy Moore seems to be very, very pumped up”.

A LEGACY IS BORN

JUST AS IN GAME 2, 1987, INSPIRED BY THE QUEENSLANDER call, the Maroon wall held firm in the second half.

The score didn’t change and Queensland won by two points.

They also won the second game in Melbourne to take the series, and the third in Brisbane for the clean-sweep, an achievement that will stand forever as one of the most momentous in Queensland sporting history.

The Queenslander call hasn’t been heard on-field much in recent years, but off-field it grows louder each year.

Those eight seconds of thundering passion changed Billy Moore’s life forever and made an indelible mark on Queensland culture.

“I know I was lucky,” Moore says.

“I was a good player, not great. I know if it wasn’t for the Queenslander call I’d be one of those players who blokes in a pub say about, ‘what was that guy’s name again?’

“I just happened to be right place, right time. My old teammate Tony Hearn was filthy. He was walking down the tunnel behind me and he’d been shouting ‘Queenslander’ too.

He’d stopped just before he got to the camera. Whenever he sees me he says, ‘It could have been me’.”

After some initial notoriety and ribbing from mates, memories of Moore’s eight seconds of fame faded.

It was several years ago that he received a call from an advertising agency that would catapult him, and the Queenslander call, back into the public consciousness.

The agency had conceived an ad campaign for XXXX that revolved around Moore dressed in a Maroons jersey “blessing” each can with a full- throated “Kerweeeeeeenssssslannnnd-arrrrrrrrr” as it came off the production line.

“That’s where it all started again. It just took off. I do about 60 appearances a year now, speaking at pubs and clubs and events all over the place. It’s mainly word of mouth. Someone I know will ring and say someone they know wants to know if I’ll go out and talk to their club. I try to go to places I’ve never been before.”

And it’s not just at sportsman’s nights and footie club fundraisers where “Queenslander” gets a workout.

It’s at business meetings and army camps, hospitals and the sites of natural disasters. Wherever a group of Queenslanders need to pull together and give that extra effort.

As Gold Coast golfer Adam Scott teed off for the round that would see him crowned Australia’s first-ever US Masters winner, a heart-felt “Queenslander” boomed out from the gallery.

Dr Amy Clarke, a lecturer in history at the University of Sunshine Coast who specialises in cultural identity (and a devout Maroons supporter) says the Queenslander call is a classic example of “collective identity”.

“It’s like when you are overseas and you hear someone speaking in an Australian accent and you think, ‘they are one of us’. When you hear someone shout, “Queenslander” you immediately know they are part of your tribe,” she says.

“It definitely goes beyond sport – you only had to see how Anna Bligh used it during the floods in 2011 – but it doesn’t hurt that we’ve smashed the Blues in recent years. It all adds to the mythology. It has a spiritual feel; it has taken on an extra power, rallying people to keep going that little bit further and sticking with the team.”

And still leading the way, at top volume, is Billy Moore.

At 48 he remains in top physical shape – he recently completed the Tokyo Marathon – which is handy, because each year he pulls on the full Maroons kit and leads the 50,000-plus crowd at Suncorp Stadium in the Queenslander call prior to kick-off at Origin matches.

“I’ve been told in the past that sometimes when I did it, down in the dressing room Cameron Smith would say to his team, ‘Hear that? How good’s that?’

“I reckon it’s got to be the biggest brand in the country, and it’s organic, it’s grown itself. There’s an honesty about it. If you believe in it it’s real. That’s why I’m proud to be the custodian. No one owns it, we just look after it and hand it on.”

Which is exactly how Fatty Vautin feels.

“I don’t know if (current Queensland coach) Kevvie Walters and his team use it these days, but they’re welcome to it. It belongs to all Queenslanders.”

And even if the players don’t use it, one thing is certain – the supporters will.

“I was hosting a function at an Origin game a few years back,” Moore says.

“There was a big group of Queenslanders and only one bloke from New South Wales. Before the game he came up to me, pointed at the crowd and said, ‘How long does it take before these idiots start screaming Queenslander?’ I said, ‘Gee mate, I’m not sure’.

“At half time he came up to me and said, ‘I can tell you. Twenty seconds. And they haven’t shut up the whole bloody game’.”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Lockyer: Real reason Maroons axed captain DCE

Maroons coach Billy Slater has failed to truly explain the reasons for pulling the trigger on Daly Cherry-Evans. Queensland selector Darren Lockyer finally sheds light on why the captain was axed.

‘Don’t kick to Spencer’: Maroons’ Leniu evasion plan revealed

NSW’s Angus Crichton has confirmed he heard Queensland’s “deliberate decision” to avoid Blues firebrand Spencer Leniu in Origin I. The star backrower also talks Maroons mind games, targeting Tom Dearden, and more.