How Matthew Hayman completed fairytale comeback from injury to win Paris-Roubaix classic

INJURED and written off even as he threatened in one of cycling’s toughest classics, Aussie Matthew Hayman just kept riding.

Other Sports

Don't miss out on the headlines from Other Sports. Followed categories will be added to My News.

BELGIUM’S soft autumn sun shines through the windows of Mathew Hayman’s Lanaken home.

Its morning light arrows into the loungeroom, where it’s stopped by a rock. Not just any rock, but a granite cobble belonging only to the victors of cycling’s most mythical one-day race — Paris-Roubaix.

The bike Hayman rode in that race is hanging nearby, unwashed and still caked with the mud from northern France’s scarred and cobbled landscape.

For the veteran Australian cyclist from Camperdown, NSW, they are the reminders of a day six months earlier that changed his life so powerfully and unexpectedly he still struggles to absorb it completely.

Ten days before his 38th birthday, six weeks after breaking his wrist and in his 15th attempt at a race that had become his obsession, the selfless Orica-BikeExchange domestique claimed the 257.5km “Hell of the North”.

After years of bad luck and circumstances beyond his control, the race Hayman has loved since moving to Europe as a teenager finally loved him back just when the expectations couldn’t be any lower.

“I haven’t actually sat down and watched the whole race because I’ll get too emotional,” Hayman told the Herald Sun.

“I’ve watched the Backstage Pass (YouTube) video a few times, but it almost breaks me.

“There was a point two days after the race when I said to (wife) Kym, ‘I can’t see any more photos and I can’t watch any more because I’m tired’. It just brings so much emotion.”

To fully appreciate Hayman’s triumph and its place in Australian sporting folklore, we need to go back to February 27 and the first classic race of the 2016 season, Belgium’s Omloop Het Nieuwsblad.

A workhorse for virtually every other race day of the year, Paris-Roubaix is Hayman’s annual one shot at glory and, as he rolled off the Niewsblad start line in Ghent, months of training in Australia, South Africa and Europe had him in supreme condition.

Then, on a right-hand turn onto a section of cobbles, it all got thrown out the window. Hayman crashed and broke the radius bone in his right forearm. Teammate Luke Durbridge was with him.

“When you go from a four-lane road to a cobbled bike lane at 60km with 180 riders it never really goes down well,” Durbridge said.

“You either make it and think, ‘Oh, I got through that one’ or you don’t, and we didn’t. We were a bit too far back ... I crashed in the soft grass on the side and Matty crashed on the cobbles.

“He was sitting on the ground holding his wrist. He looked up at me and just shook his head.”

Hayman had been around long enough to know the score.

“I didn’t want to get in the ambulance because I didn’t want it to be true,” Hayman said.

“The doctors said it would be at least six weeks and that was being positive. I did the calculations and that had me back the day before Roubaix, but they were shaking their heads saying, ‘There’s no way you’ll be riding Roubaix’.”

Orica-BikeExchange released a statement declaring Hayman’s classics season over. The team even moved his bikes to its service course in Italy.

“The hardest thing for him was the realisation you can be riddled your whole career with bad luck,” Durbridge said.

“You can be in the form of your life and have a crash like that and, once again, after 15 years of trying for the big breakthrough result it’s taken away.”

But Hayman couldn’t face throwing in the towel. He got home, went to the garage and sat on his stationary trainer. Unable to hold the handlebars, he got a ladder and rested his plastered right arm on the top step.

An old teammate then recommended Zwift — a computer training partner that pits riders against each other in a virtual world — and Hayman was soon hooked, completing 100-minute sessions in the morning and evening.

Still, as the weeks rolled on and the cast became a brace, the doubts remained.

“The whole time I was doing it I was asking myself and anyone I spoke to, ‘What the hell am I doing? Where is it leading? Is it worth it?’,” he said.

But the numbers said Hayman had made progress and after he finally emerged from his garage for two one-day races in Spain, the decision was made to start him at Paris-Roubaix.

“We actually didn’t decide to start him until a week before the race,” Orica sports director Matt Wilson said.

“He’d come off that injury and it was basically like ‘Oh well, he’s got a lot of experience, let’s put him in’. You could say our expectations were low.”

When Orica-BikeExchange gathered for a reconnaissance ride three days before the race, the team saw a different Hayman to the one taken away in an ambulance six weeks earlier.

“We had two motorbikes and we pretty much did the whole course. Matty was on this different mission,” Durbridge said.

“We were riding behind the scooter doing pacing and Matty was riding off the back or in front of the scooter. We were just like, ‘Matty, chill out, the race is on Sunday’. He just looked at us like, ‘What would you know?’.”

Hayman was cramming and while no one else believed, he had started to.

The night before the race, Hayman had separate visits to his room from Wilson and Dan Jones, the team’s video producer.

“I said, ‘Oh mate, it’s unbelievable you got a start’ and he was quite p-----d off that I was writing off his chances,” Jones said.

Hayman read Wilson an email he had received from his coach Kevin Poulton, which stated he was back to producing some of his best power. But both men agreed that while he might be good for 200km there was a real risk of the “lights going out” in the final.

In the team bus the next morning a plan was laid out to protect Durbridge and Jens Keukeleire.

“In the pre-race meeting we didn’t even talk about Matty,” Durbridge recalled.

“It was like, ‘Matty, you get through 120km and that will be great, that will be perfect’. Matty was just sitting there like, ‘You wait. You wait’.”

After years of mainly self-inflicted pressure, Hayman rode with freedom. He got in the early break with 14 others and with 20km to go he’d found himself in a select group of five that included Belgian superstar and four-time Roubaix winner Tom Boonen, Ian Stannard, Sep Vanmarcke and Edvald Boasson Hagen.

Still, he was given no chance. Back in the Roubaix velodrome the announcer was asking fans who they thought was going to win by giving them four names to choose from. Hayman wasn’t one of them.

When Stannard inadvertently ran him wide on a tricky left-hander with 16km to go, the unfancied Aussie was gapped. It was supposed to be curtains, except it wasn’t.

With former Canadian rider Mark Walters’ words — “Always keep riding” — ringing in his ears, Hayman fought back, led out the sprint in the velodrome and triumphantly raised his arms across the line nearly six hours after starting out in Compiegne.

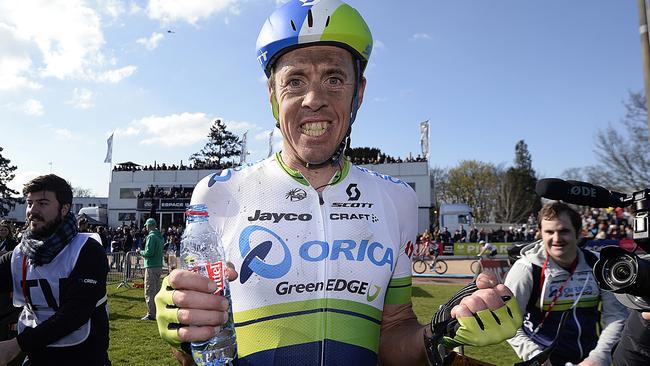

In his 17th year as a pro and riding his 15th Paris-Roubaix, the then 37-year-old had never before made the Paris-Roubaix podium. His look of genuine shock after crossing the line was the enduring image of the race.

Roger Federer was famously given a cow after winning Wimbledon for the first time. Hayman was given a year’s supply of beer.

“Those 15 years, I think I had to go through all that to have the knowledge and to just be in the perfect mental state. Sometimes the pressure I’ve put on myself just for that one day has stymied me in a way,” Hayman said.

“As far as my cycling career goes, it’s validated everything. It’s very much a fairytale for me and I couldn’t have asked to win a more special race.

“Without it, there could have been a ‘what if?’. But all the time you’ve ever spent and all the sacrifices you’ve made have been that bit more worthwhile and made it that much sweeter.”

On that Backstage Pass video, the musical backdrop to Hayman’s win could not be more apt.

It is Hans Zimmer and Lisa Gerrard’s emotional Now We Are Free.

Now, near the end, Hayman is finally free.