Sandpaper-gate: Behind Australian cricket’s ball-tampering downfall

AUSTRALIAN cricket is still living with the cataclysmic repercussions of the ball-tampering scandal but how did it come to this? Geoff Lemon explores the nitty gritty of ‘Sandpaper-gate’.

Cricket

Don't miss out on the headlines from Cricket. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Through the build-up and the sandstorm, it can’t be said that coach Darren Lehmann often asked the right questions at the right times. Once, though, Australia’s coach did offer the most pertinent query.

What the f..., indeed, was going on? A professional national representative team, paid in the upper echelon of athletes in the world, in a sport thick with talk of fair play and respect, cheating in a way that left no grey area, ham-fisted in the attempt, leaving a junior player to do the work, then being so startled when the high likelihood of being caught became real that they ducked their heads and tried to lie their way out. How did this possibly come to pass?

To answer, you first have to ask: how long has this been going on? Cricket Australia’s investigation exposed lies about sandpaper and David Warner, but otherwise its conclusions mirrored captain Steve Smith’s initial claims: that only three people ever had an inkling, and that Cape Town was the only incidence. No Australian ever considered tampering until the inspiration struck in the second half of a Test in the second half of a series, then was exposed within an hour of that newborn idea taking its first slow blinks in the sunlight.

All series the ball had moved extravagantly. Yet halfway through the third match, Australia’s ball conditioners had apparently lost their entirely legal ability to extract swing. Smith even offered the precedent as amelioration: “We’ve seen the ball reversing quite a lot throughout this series, and our ball just didn’t look like it was gonna go.”

At lunch on day three, when the plan was supposedly hatched, that ball was 22 overs old.

Reverse swing generally kicks in after 40 or 50 overs. So we were asked to believe that in Cape Town, Smith agreed to a tampering plan because a ball wasn’t doing something that it couldn’t have been doing unless it had been tampered with. Was this really the company line?

It was true that Cameron Bancroft had been sufficiently unskilled that he was caught in quick time. But equally implausible was the insistence that Bancroft’s first time was also Australia’s. He was under surveillance because suspicions were high.

Scrutiny in Port Elizabeth was what made Warner recruit a new ball-shiner in the first place.

South African players believed they’d seen tampering first-hand. Media connections had spoken on air. Television cameras had suspicious footage.

There was a misleading impression that (head of integrity Iain) Roy’s investigation covered the whole team when he had only interviewed Warner, Smith, Bancroft, Lehmann and Peter Handscomb. No other player had to sit down with a trained cross-examiner exploring what they knew. Lehmann’s supposed corroboration had no source. It was either a huge oversight or a convenient omission.

Possibility raised

The thing is, South Africa were reversing it just as early. That doesn’t have to mean they were tampering, maybe they were managing the ball to perfection. But it raised the possibility. Did Australian suspicion have an influence before South African suspicion? Warner said on the first night of the series: “The ball shifting after 20-odd overs on the first day is incredible.”

Now consider Warner’s pachydermal memory for grudges. He had history with South Africa and tampering. In 2014 when AB de Villiers was the wicketkeeper, Warner noticed he would collect throws from the outfield, then brush the rubber pimples of his glove over the rough side of the ball. Warner made the accusation in a radio interview after losing the Second Test.

The ICC fined him for inappropriate comments, then umpires in the Third Test told de Villiers to stop brushing the ball.

In that bad-tempered third Test of 2014, Warner led the “pack of dogs” confrontation that saw Faf du Plessis barked off the field. South Africa struggled for swing. Australia didn’t. “I was really surprised to see the ball reverse from their side. It was 20 overs old and with the damp conditions … let’s just leave it at that,” said du Plessis with an artful pause.

After du Plessis’ mint charge in 2016, Smith was conciliatory and said that everyone uses that technique, while Warner gave a speech about how disappointed he would be if his team ever stooped so low. In 2018, when South Africa got swing at Durban, what are the odds that Warner decided it was dodgy? What are the odds it started an arms race?

It fits an earlier theme: anyone getting away with something makes Warner want to even the score.

Having just moved back into the slips, tape was a fair precaution for Warner’s damaged fingers. Warner routinely taped his left thumb and index finger, wrapping a sheath around the digits as he had through the Ashes. Now he had a cross-strap, a thick band of tape running across his palm below his fingers.

As they batted in Port Elizabeth, South African players swore things were amiss. The tape on Warner’s palm, they started to think, was sticky side up.

That theory got passed on to broadcasters. Reports began to circulate questioning Warner’s bandages, and the following morning camera close-ups found the names of Candice and his daughters freshly inked onto the new tape. Recasting an object of controversy as a sweet family tribute was a clever riposte.

Family was the central factor, anyway. If Warner hadn’t been tampering before the stairwell fight with Quinton de Kock in Durban, surely it was the catalyst. If he had been, it would have made him feel justified. Through the second and third Tests, as abuse of his wife intensified, Warner was coming back to the hotel each night to find her crying and blaming herself for the drama. Warner loves Candice Falzon more than anything. He credits her with making his life worthwhile.

They were both besieged. The ugliness leached through the touring party and the series. Experienced match referee Jeff Crowe said it was the angriest series he’d ever seen. The players union boss Alistair Nicholson thought the same when he arrived: “The environment that I encountered prior to the Test at Newlands was the most hostile I have witnessed since I began this role.”

Under all this, Smith was falling apart. He’d come right out and said during the tour that he wasn’t mentally right: “I didn’t feel I was hitting the ball that well but my mind was in a good place, maybe now my mind is not in as good a space as it was but I’m hitting the ball better.” And, “It got to the point where I actually didn’t want to pick my cricket bat up for a bit which is very rare for me.” No one picked up on the significance.

South Africa swarmed him as they’d done before. He hadn’t made a ton against them since his first attempt in 2014. He was so plumb in Port Elizabeth that he started walking, then stopped and reviewed it just in case. In Cape Town he was out twice to a trash shot at a trash ball from a bowler who rarely threatened.

Later Smith would speak about the one-dayers he’d played after the Ashes. “I think it all comes down to the mental part of the game and just putting so much into the Ashes back home that it took so much out of me.”

Small wonder that horrible decisions were being made in the dressing room as well. It also revealed that Smith had never been much of a leader to begin with. A great cricketer, a decent tactician, but not someone who would set the path or demand the behavioural standard.

The 2015 clear-out that made him captain also stripped senior experience from his side. Nathan Lyon had played the most but never quite believed he belonged. Mitchell Starc and Josh Hazlewood were good-natured and played along. Usman Khawaja was quiet, Shaun Marsh was silent, Mitch Marsh was a cheerful goof.

New boys only wanted to impress, Bancroft to his detriment, Handscomb grinning and chirping like one of those schoolkids wanting to win favour with bullies. None of them would stop Warner doing as he pleased.

And so to the final piece of the puzzle. In November 2016, when Australia was shot out for 85 by South Africa in Hobart, the game’s authorities hit a well-worn crisis button. Rod Marsh resigned as chairman of selectors while his colleagues sacked five of 11 players. The “quiet” wicketkeeper Peter Nevill was ditched, the new man Matthew Wade would “bring back the mongrel”. In short: Nevill didn’t sledge and Wade didn’t stop.

The clear lesson was that management demanded aggression.

When things got dark in South Africa, Smith didn’t have a guiding store of principles to draw on. All CA had drilled into him was to win and back up your mates, the classic Australian way.

Smith was crumbling, strung out, manic. Warner was enraged, acting out, and had the longest track record in the game.

PR advisers pip lawyers

From the start there were rumblings from Warner’s camp that he wasn’t to blame. CA’s report indicated that he’d made the plan, Bancroft was the stooge, and Smith didn’t snuff it out. Warner took several more days to make a public appearance than the others, and did so with careful scripting that limited admission of liability. Only the goodwill that Smith and Bancroft attracted for their apologies saw Warner accept his sanction, as the PR advisers pipped the lawyers.

As in 2015, when Clarke and Lehmann denied asking him to sledge, Warner remained adamant that he had done what they wanted. Is this a moral relativism, or did others actually know?

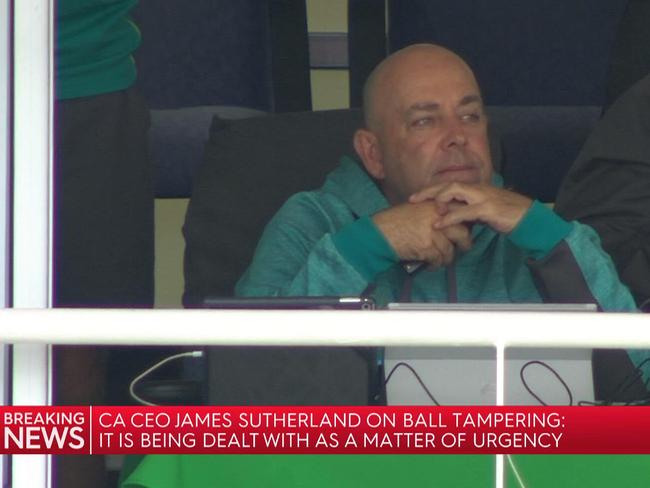

When the sandpaper story broke, Sutherland adopted his basset-hound air. “In recent times, as I think most of you know, I’ve had reason to speak to Steve about the team’s behaviour, and we put a media release out recently about that. I have very strong and clear views about the responsibility of the Australian cricket team to play the game in the right spirit, and I don’t think anyone would be under any illusions within the team as to what I think about this.”

Talk of being held to account was hollow; Warner never was. He was encouraged and enabled. It didn’t matter whether anyone started telling him to stick the boot in. It mattered that no one had stopped him doing it before. Australia wanted to use Warner’s temperament but ignored an ancient lesson: elemental forces are never fully controlled.

Fire, water, electricity, gravity, velocity: all can be bent to your purpose, but you respect their damaging potential and you never ease your vigilance. Those running the game could have worked towards better awareness, better standards, an aim of being better people, but had failed at each. All that remained was the poor theatre of condemning one’s own creation.

This is an edited extract from Steve Smith’s Men by Geoff Lemon published by Hardie Grant Books RRP $29.99 AU and is available in stores nationally from 1 November 2018.

Originally published as Sandpaper-gate: Behind Australian cricket’s ball-tampering downfall