Dean Jones death: How Elton John saved late Aussie legend from making huge financial gamble

It’s such a strange tale you’d be forgiven for thinking it was made up. But no. Here’s the story of how Elton John saved Dean Jones from losing one of the biggest gambles of his life.

Cricket

Don't miss out on the headlines from Cricket. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Dean Jones was always an entertainer, but it took one of the greatest entertainers of all to save him from losing his house.

The year was 1999 and Jones was about to go all-in with his event management company on a multi-million dollar investment to bring David Beckham’s all-conquering Manchester United to Australia.

Jones’ three-man consortium had recently brought the FIFA World XI down under to play the Socceroos and had got INXS back together following the passing of Michael Hutchence to officially open the Sydney Olympic Stadium ahead of the 2000 Games.

Watch every match of the 2020 IPL Season LIVE on Fox Sports with Kayo. New to Kayo? Get your free trial now & start streaming instantly >

DEAN JONES NEWS

The layer of sadness behind Deano tragedy

How Jones, Hadlee became cricket’s quirkiest union

Jones was set for national team role

Despite the mega event turning over $15 million, Jones vowed never to take such personal risk again, after the stress of putting his house on the line for a $5 million loan, which was in doubt until the morning of the show, with members of INXS considering pulling out at the last moment.

But following that ultimate success, Manchester United came knocking, eager for an Australian tour after winning European football’s Triple Crown. And they wanted Jones’ company to put up over $10 million for the privilege.

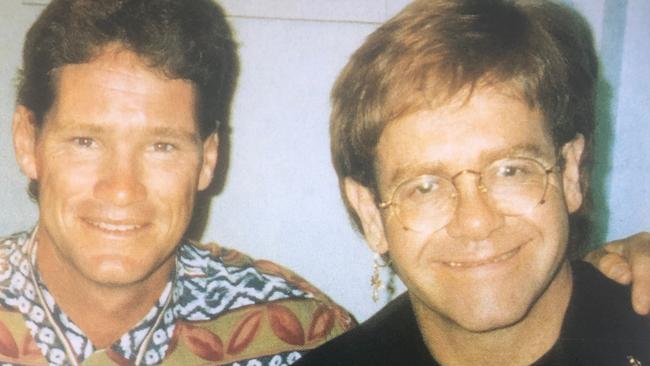

Jones says he was on the verge of signing on the dotted line to take one last plunge, before he excused himself from a meeting with Manchester United heavies to visit long-term friend Elton John in his hotel room at Crown Casino in Melbourne.

“I said, ‘I’ll tell you what, can we do this tomorrow, because I’ve got an appointment’,” Jones recently recalled on a podcast hosted by fellow cricket great Shane Watson in June.

It was moments later in John’s room he received a bombshell tip-off from the music icon that he says saved him from financial ruin.

“I told Elton what date they were playing (in July) and he said, ‘Dean, I’ve got a confidentiality agreement so I’m going into the next room. You need to look on my desk,’” Jones recalls John telling him.

“I walked across to the desk and there was the invitation for him to play at Beckham’s wedding which happened to be the same (time).

“And I’ve gone, ‘ohhhh, so half the team is going to be with Beckham!’”

Plenty of superstars still came out for matches in Melbourne and Sydney in front of massive crowds, but half of the famous Manchester United starting team – including coach Sir Alex Ferguson – were absent, with Paul Scholes, Roy Keane, Gary Neville and, of course, Beckham not making the trip, as well as recently departed keeper Peter Schmeichel.

Jones says he quickly sold the rights to businessman Rene Rivkin and believes John’s subtle wink-wink, nudge-nudge about the date of Beckham’s nuptials saved him from potential financial ruin.

“I went back to them (United management) and said, ‘is that date right?’ I said, ‘you’ve got nothing on?’ They said, ‘no.’ And I knew they were lying,” Jones told the Watson podcast.

“They didn’t care. Not worried about advertising these guys’ names and they don’t turn up.

“Rene Rivkin was also trying to bid for it and I gave it to him for $200k and he ended up taking the heat.

“And half the team never turned up. You know what? I would have lost my house and everything … event management is a lot of fun, but it comes down to your networking.”

With John as a friend, Jones couldn’t have been better connected.

The bond between the legendary performer and cricketer was mutual.

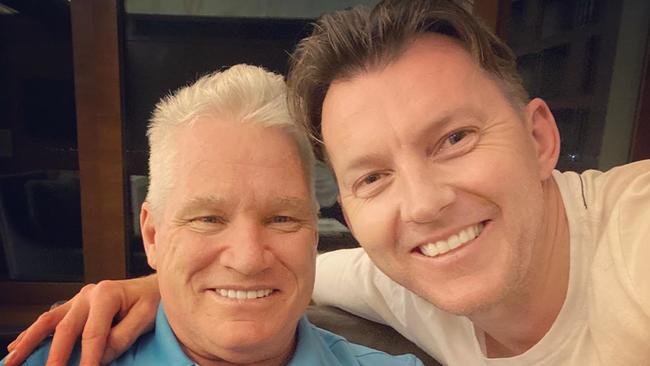

Elton John paid tribute to Jones following his tragic death from a heart attack last Thursday, posting on twitter “Life is unfair” next to a smiling photo he had recently received of Jones and Brett Lee.

“Only last week I was sent this lovely photo of Dean Jones and Brett Lee in Mumbai,” John wrote.

“Now Dean has gone. Life is unfair. He was a great cricketer and a wonderful father. My love and condolences to Phoebe, Janey and Gussie. #RIP.”

Border’s first impressions of young gun Dean Jones

I was at the other end when Dean Jones made his Test debut and I swear he gripped the bat so tightly the glue was almost squeezed out the end of his handle.

You couldn’t blame him. It was a dirty day and a moist wicket in Trinidad and Deano made his entrance at No.7 with Australia 5-85 against an attack that included Joel Garner and Malcolm Marshall.

When we spoke mid-wicket his eyes were popping out of his head. It was as if he had drunk 100 cups of coffee. He was jumping around like a cat on a hot tin roof as the ball whizzed past his nose.

But he wore a few and somehow made 48 and I thought straight away “this kid has something special.’’

Thrown in on the morning of the game, he had courage in spades.

From that innings until the last time we spoke on the day of his death I was a Dean Jones fan but our relationship stretched deeper than that.

Even as I pen these words, I feel a sense of numb disbelief that my former teammate and great friend is no longer with us.

Scott Styris, who was in Mumbai commentating with Deano, rang me with the news while I was watching the Broncos just after 8pm on Thursday and my first reaction was “this could not be right’’.

Initially I thought he was recovering after a heart attack but Scott said “no, he’s gone”.

I just could not process it. I generally don’t get too emotional but I did last night.

I had spoken to Deano earlier in the day. He has always been an ideas man and we were looking to going into a wine-making venture together. It was exciting stuff and a bit of fun. That was Friday morning. Then suddenly he was gone.

My phone rang off the hook but I could barely speak to reporters without choking up. I’m not normally like that.

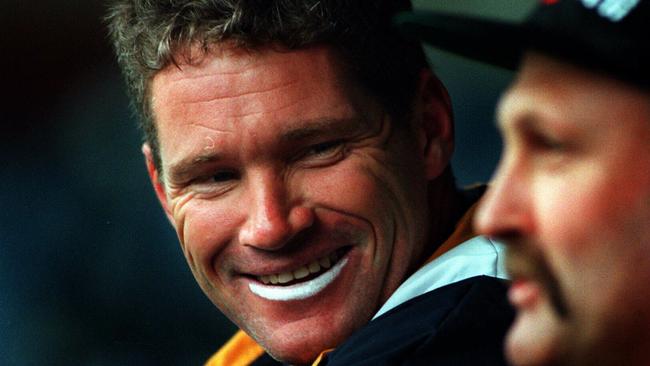

Deano and I were opposites in so many ways but we just got each other. He would push my buttons and question things – yes, it did occasionally burr me up – but I enjoyed his banter. He always had my back as a captain and that meant a lot to me.

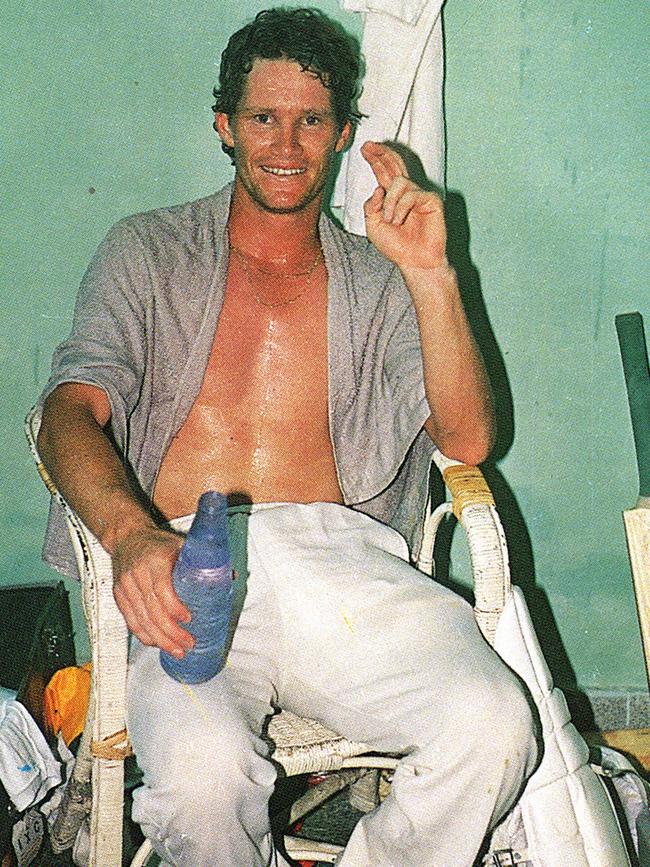

I have so many vivid memories of Deano including batting with him during his innings of a lifetime – his 210 in Madras. He was totally spent with dehydration when he got to 170 and said to me “I’m shot – I’m going off’’ and I knew I had to find a way of stirring him up so I said “let’s get a tough Queenslander (Greg Ritchie) out here.’’

A proud innovator and boundary pusher, he was the first player to wear sunglasses on a cricket field.

I remember saying to him “mate, I just hope and pray you take that first catch – don’t worry about Bob Simpson, I’ll be having my say. You are already a mug lair ... do you really need any more dramas in your life?’’

Sure enough, Deano was ahead of the game and a year later I was wearing them.

In 50-over cricket he was the first guy to really challenge the fielding team with quick running.

Let me say this about Deano – he was an underrated player. Do you reckon the current selectors would like to have a batsman averaging 46 after 52 Tests up their sleeve?

I’ve enjoyed the old replays of 1980s ODIs on Fox Cricket lately. They proved to me that the game has improved and changed but Jones’ technique was timeless.

It looked excellent back in the day and it would stand up just as well today – and there are plenty that wouldn’t.

He played his last Test in 1992 and quite clearly we cut him far too soon. He blamed me for this and used to goad me at sportsmen’s nights where we would be on stage together and he would ask “so AB, why did you end my Test career?’’

He enjoyed putting me on the spot.

I wish I had a decent answer but he got me every time.

I enjoyed the way he challenged things with unconventional theories. It disappointed him that he could not land a coaching role of a major nation and I share that regret because he could have been successful.

In my last season in Australia we went out for a few innocent beers in Sydney the night before a one-dayer and saw this promotion of a beer launch where you got a free beer if you threw a ping pong ball through a hula hoop. People were struggling to do it and I could not help myself.

I was normally not so adventurous but Deano and I just kept threading the needle and getting free beers, wobbling home at 3am, somehow avoiding the wrath of “detective inspector’’ Bob Simpson.

It’s memories like that made me smile through the pain and reinforced what I already knew – that Dean Jones was someone I cherished as a man and a cricketer and I will miss him greatly.

MORE ON JONES:

Adam Gilchrist reveals why Dean Jones was his favourite player growing up

Dean Jones dead: Mark Waugh says the architect of modern cricket deserves highest honour

UNDERAPPRECIATED DEANO A TALENT LIKE NO OTHER

- Ron Reed

Sometimes very good people have to die before they are fully appreciated. Sadly, there has been an element of that as the tributes have flowed freely and generously for Dean Jones, a cricketer who stood out from the crowd in every way – and who wasn’t always made as welcome as he should have been.

For a player of such obvious talent and determination he was on the receiving end of some rough treatment from the national selectors and other heavy-hitters from time to time, and there is no doubt he deserved to play considerably more than the 52 Tests he did during the eighties and early nineties.

As a coach, he was far more in demand in Asia – where he fashioned a highly successful second career of it in Pakistan, Afghanistan and elsewhere – than he was in Melbourne, where he grew up to become Victoria’s greatest player of the last 50 years behind only Shane Warne.

So it is beyond regret that only six months ago he felt so angry and frustrated at being overlooked – snubbed, in another word – as new coaches were sought for the Stars and Renegades Big Bash teams that he cut all official ties with Cricket Victoria.

Critical also of other aspects of the way the game was being run and offended that he seemed to have encountered a communications brick wall, he handed back the life membership bestowed on him in 2011 and demanded his name be removed from the award for Victoria’s best one-day player.

Unfortunately, that rift did not have time to get resolved, although CV executive Shaun Graf said yesterday that when the dust settles Jones’s family will be consulted on returning his name to its rightful places of prominence.

Deano, as he was known to everyone, was a born coach and commentator – another role in which he excelled, on radio and in print – because he was such a deep and often lateral thinker about all aspects of the game, which he wanted to share as widely as possible.

He enjoyed the cut and thrust of the media and established firm friendships with a wide range of journalists, some of whom (us) he played cricket with on a casual basis long before he made it to the big-time, and who would often find themselves tapped on the shoulder in the Press Box and invited to swap opinions on whatever was happening out on the field – or off it.

Some cricketers are best remembered for their stats. That won’t be Deano. His greatest legacy will forever be the stupendous 210 in Madras in weather so debilitating he ended up in hospital on a drip.

The Australian coach at the time, Bob Simpson, described it as the greatest innings ever played by an Australian – but in fact it is probably in the top handful of individual feats across the entire national sports spectrum. Ever.

That bravery was also evident in his regular battles with the frightening fast bowlers from the West Indies who dominated his era.

His flair for the then-evolving 50 over format – where he took running between the wickets to a new level and fielded with rare ferocity -- also put him in a class not quite of his own, perhaps, but certainly as a pioneer of what was possible in terms of innings totals. If Twenty20 had arrived a few years earlier he would have taken it by storm.

While numbers can never define him, it is worth noting his Test average was 46.55, which translates between very good and exceptional. It might surprise that of the 28 Australians who have scored more Test runs than his 3631, only 15 have better averages and then mostly only marginally.

Without denigrating anyone else, Mark Waugh – widely-regarded as an all-time great – is an interesting comparison. When Jones was unexpectedly dropped against the West Indies in Brisbane in 1992 he had just topped the averages in a tour of Sri Lanka, while Waugh was making four successive ducks.

Jones, shattered by the bullet he never saw coming, never made it back while Waugh went on to play 128 Tests in which he averaged 41.81, which is a significant gap at that level. He also averaged 39.35 in 244 ODIs against Jones’s 44.61 in 164.

There are other examples and they did rankle, especially as it became clear in South Africa two years later that he was never going to wear the baggy green again.

A lawyer, probably farcically, suggested he sue for restraint of trade but of course that was never going to happen, any more than he was going to take the big money he was once offered to make a rebel tour of South Africa. His respect for the game – drilled into him by his father Barney, a famously combative club cricketer – would never have allowed any of that.

He was an easy character to like, excellent company, unfailingly interesting and entertaining when cricket – or footy – was on the conversational agenda, which it nearly always was.

But that doesn’t mean he wasn’t a polarising figure in many respects. As Victorian captain he set high standards for himself, setting a cracking pace in all aspects of preparation and was ruthless in expecting others to keep up. “The weak failed under him because they couldn’t cope with the pressure,” says team-mate Darren Berry, who followed him as captain.

Berry likened him to Michel Jordan, the legendary American basketballer whose intolerance of team-mates’ dedication and work ethic was featured in a recent documentary that transfixed the sports world.

“Deano couldn’t understand why people wouldn’t train with the same intensity,” he said. “He didn’t suffer fools easily.”

Berry, who was among those who temporarily fell out with him before resuming a close mateship - he likened it to “Batman and Robin, and you can guess who was who” - believes Jones was like many top sportsmen who could come across as arrogant and brash but were, deep down, insecure and simply craving respect.

That’s a major reason why he made nearly 150 trips to India to play, coach and commentate. People there never forgot the Madras epic and idolised him because of it. He felt the positive vibe there more than he perhaps did in his own home town, where once every kid growing up had wanted to be like him – a swaggering, swashbuckling hero of the national game.

“He was loved by the masses but had to learn to be close to those around him,” Berry said.

There is a strong school of thought among some of his peers that if Jones had not been such a maverick he might have sometimes found it easier to get the nod from selectors, and that wasn’t lost on him as he moved well into retirement.

When it was brought up in conversation he would shrug it off on the basis that Dean Jones was Dean Jones for better or for worse.

The “better” was what the cricket world – all of it – is remembering today, and the only regret is that there could have and should have been more of it. But what we did get, nobody would want to change.

RON REED is a former Herald Sun sportswriter who covered Dean Jones’ career from start to finish.