Australia vs India, first Test: Nathan McSweeney’s strengths and weaknesses analysed

Nathan McSweeney’s selection as Test opener has been divisive. CricViz data proves the debutant is already the world’s best player in one department, but there remain red flags.

Cricket

Don't miss out on the headlines from Cricket. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When it comes to opening partnerships, Australian fans are familiar with the unfamiliar. In the past 10 home summers, only once has the opening pair who started the previous season walked out to bat at the start of the next.

Despite the longevity of David Warner, and the recent success of his partnership with Usman Khawaja, Australia are used to changes at the top of the order.

This year is no different. On Friday, Nathan McSweeney – toss permitting – will become the 170th man to open the batting for Australia in Test cricket.

However, unlike the vast majority of his predecessors, the 25 year old Queenslander has barely done the job before. He has opened in just one red ball match, for Australia A a few weeks back. Never before this season, never in the Sheffield Shield.

So why is he opening against India?

Well let’s underline the simple stuff first – McSweeney has scored a proper chunk of runs in domestic cricket. Since moving to South Australia for the 2021/22 season, he has averaged 42 in the Shield. In those seasons, only three guys have averaged more than him (among those to play at least 20 times): Cameron Bancroft, Peter Handscomb, and Beau Webster.

There is clear evidence that he’s improving as well. Going back to the start of last season, McSweeney’s average rises to a tick under 50, with four hundreds in 12 games. And yet despite this strong record, there has been a fair amount of frustration at McSweeney’s promotion.

A significant part of that is people’s perception of how much you need to dominate domestic cricket before getting a crack at the level above. In the past, you needed to be knocking out 1000 runs a season to be catching the eye of selectors, but times – and conditions – have changed.

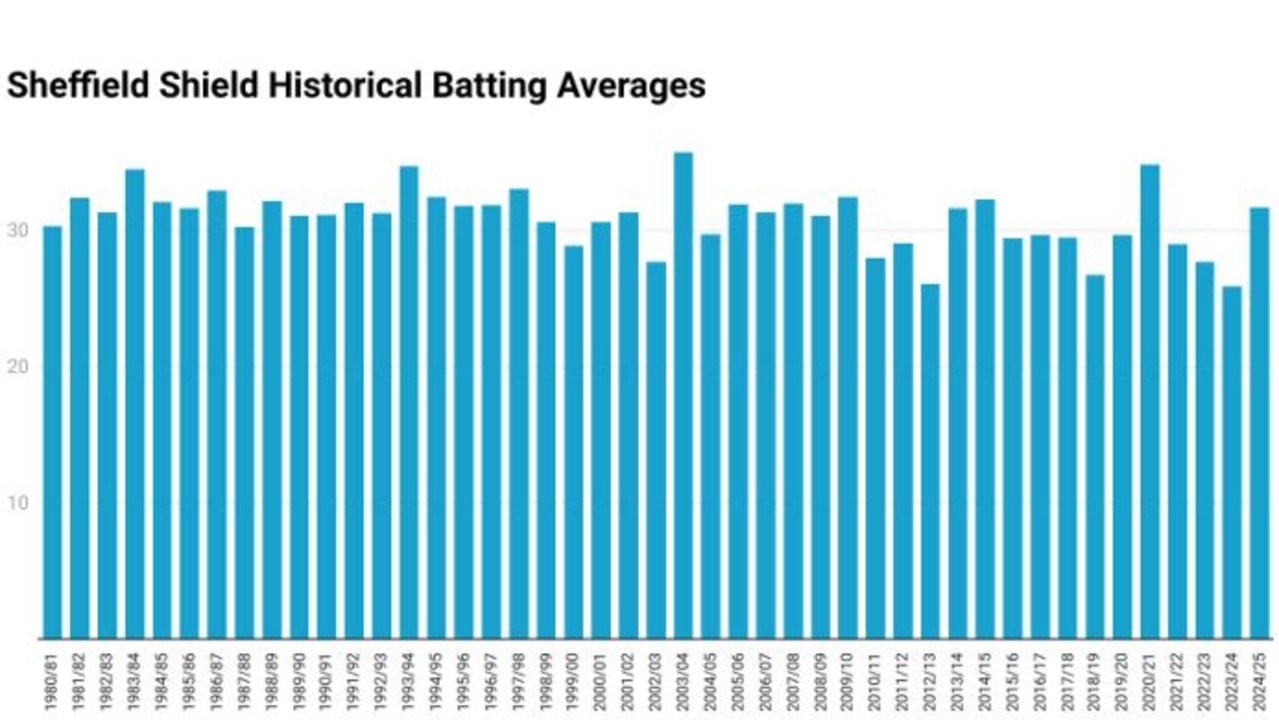

McSweeney may not have the bank of runs that was needed to stand out in years gone by, but nobody does. From 1980 to 2000 overall batting average in the Shield dipped below 30 in just one season; in the last 15 years, the trend has reversed with only four seasons averaging above 30. We need to think about selection a little differently.

The more interesting element of the frustration centres around the specific job McSweeney is being asked to perform. Almost all of his red ball runs have come at No.3 or No.4, not opening the batting, maybe the most specialised position in a batting order. So, let’s take a look at McSweeney’s record in a bit more detail, to see whether his game is suited to that speciality.

In the last four seasons, McSweeney’s stats are skewed by an excellent record against spin bowling, against which he averages just under 70 runs per dismissal.

Aussie fans may be slightly concerned that his average drops to 40 against pace bowlers; however, that profile isn’t unusual for a Shield batter.

This is a competition where spinners struggle in general, and where seamers’ stats are always boosted by the new ball.

If you actually stack McSweeney’s record against the quicks up against the other runners and riders, he comes out well – only Webster betters his average.

The one element of McSweeney’s game which separates him from Bancroft, Harris et al is his record on the back foot.

In the last four seasons, playing pace off the back foot, McSweeney averages a staggering 149 runs per dismissal, easily the best in the Shield. Take that a step further if you’d like; from first-class competitions where there is collected shot-type data, McSweeney’s back foot average is the best in the world.

On a simple level, the challenge of opening the batting is facing the new ball. You can debate precisely when the ball stops being ‘new’, but the data broadly suggests it’s after 20 overs – and during this period, McSweeney has done well. Even with the mitigation that he’s coming in later than the opening batters, his record in this phase is more than comparable to Bancroft and Harris.

However, there are some causes for concern. Against bowlers who have played Test cricket, McSweeney’s average falls to 32.

It’s an imperfect measure, with many of those bowlers at the back end of their career rather than actually being international standard right now, but it’s still something of a guide.

Similarly his defensive record, particularly against pace (a dismissal every 60 defensive strokes) does not necessarily paint the picture of a Test opener in waiting.

All of Bancroft, Harris, Webster and Renshaw boast better defensive records in recent Shield seasons.

There’s a long history of Aussie openers who battered bowling off the back foot, but their success was as much about diligent front foot play as brutally cutting and pulling.

In short, there is more than enough in the numbers to suggest McSweeney can make a success of his new role. The psychological shift from batting first drop to opening is clearly substantial, but his record facing the new ball feels like a good indicator he can cope with it. That defensive solidity will be a worry, and will need to improve, but right now you would back the good to outweigh the bad.

More Coverage

Originally published as Australia vs India, first Test: Nathan McSweeney’s strengths and weaknesses analysed