Vale Ron Barassi: Reflecting on the life, achievements and importance of one of Australian football’s most revered and respected figures

Ron Barassi is Melbourne’s greatest figure, forever lives in Carlton folklore and turned North into a premiership force. Glenn McFarlane reflects on the life of a man who did so much.

AFL

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It was midweek in September of 2021 that Ron Barassi stared down the barrel of the camera and belted out a passionate rendition of the Melbourne theme song.

The champion player and master coach’s mind had been slipping, limiting his public outings and putting an end to his speaking engagements, but Barassi could still sense the occasion.

Sitting in his St Kilda lounge room, the Demons Legend finished his singing and then urged on the famous club’s current day side to break a 57-year-old curse and win Melbourne’s first premiership since 1964.

“We’ve waited so long; it would mean so much to so many people,” Barassi said.

“It would be absolutely beautiful … it would be fantastic if we can win one after all these years. Can we win it? Hell yeah! We are going to win it.”

Two weeks later, Barassi got to watch and cheer on that historic premiership from his home as Max Gawn’s hungry Melbourne side demolished the Western Bulldogs during the Perth grand final — a match relocated away from Melbourne for the second time in history because of Covid.

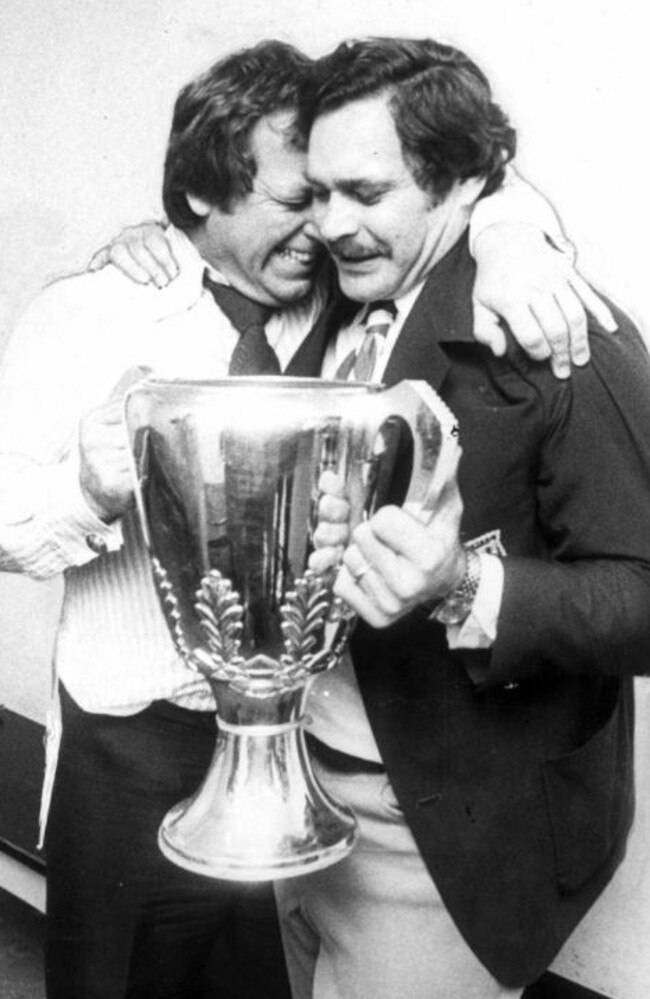

Two weeks after that he was pictured gloriously holding up the Cup. The same thrill he experienced as an inspirational Melbourne player six times — in 1955, 1956, 1957, 1959, 1960 and 1964. He captained the side in the 1960 and 1964 wins.

Barassi has always been Melbourne’s greatest figure, and now we are mourning his loss.

Throughout his career, Barassi was renowned as one of the competition’s most determined players, who influenced games through skill and sheer willpower and who never conceded defeat.

As a coach, he was fearsome, ruthless and inspiring.

He led Carlton to premierships in 1968 and 1970 before crossing to North Melbourne to taste success in 1975 and 1977.

Barassi stamped himself as a winner, but his early life was shrouded in sadness and loss.

In July 2021, he marked 80 years since his father, Ron Sr., was killed at Tobruk in 1941, aged 27.

Barassi, who was born in Castlemaine to Ron Barassi Sr and Elza Barassi in 1936, was only five at the time and could barely remember anything other than the telegram arriving with the tragic news.

“My mother and I were staying with my uncle and his family in Footscray,” he said.

“I remember the telegram (detailing his father’s death) arriving at the house. It was just a scene of utter grief. War is a terrible thing.”

Ron Sr. played in Melbourne’s 1940 premiership side – 10 months before his death.

Barassi said he had continued to feel his father’s absence more and more through the years, making two trips to his grave in 1984 and again in 2013.

“I had dreamt about visiting his grave over the years and it became a reality when Cheryl (his wife) and I went there in 1984,” he said.

“I don’t remember anything I said, but I do know that I said: ‘Dad, I love you!”

“Although I was only five when he was killed, he’s always been a hero to me. I spent a fair bit of time crying.

“I had thought about trying to investigate bringing him home to Australia. But I think if he had anything to say about the matter, he wouldn’t want to come back.

“I reckon he would have wanted to stay with his mates.”

If Barassi was driven by his father’s ghost, it was his mother who was determined he would not grow up soft and insisted that he never back away from a fight.

She became a powerful influence in his early years and teen life, instilling in him a belief that the only way to conquer fear was to refuse to show you were scared.

Barassi’s mother remarried and moved to Tasmania in the early 1950s, but young Ron had fallen in love with football and the Demons.

Despite being zoned to go to either Collingwood or Carlton, Melbourne lobbied the VFL and grabbed the rising young star from Preston Scouts as a father-son recruit – only the second player to be taken under the emerging rule.

This historic moment connected Barassi with his father’s club and aligned him with a leader of men and a mentor who would significantly shape his career, the legendary Melbourne coach Norm Smith.

With his mother’s blessing, her then 16-year-old son moved into a bungalow at the back of Smith’s Pascoe Vale home in 1952.

He credited sitting down to Sunday roasts with the master coach as a crucial factor in the way he viewed and approached the game.

“Norm was very good at judging a person’s attitude and putting them back in their place,” Barassi told the AFL Record.

While he made his senior debut the following year – aged 17 years and 79 days – wearing his father’s No. 31 against Footscray in Round 4, he spent the entire game on the bench as 20th man.

He was never quick but his ability to play both tall and small with a high level of skill encouraged the innovative Smith to revolutionise the ruck-rover role in 1954.

“In those days clubs selected two ruckmen to contest the hit-outs at centre bounces and around the ground,” Barassi said.

“But Norm Smith decided to use me as a mobile ruck-rover and that’s pretty much stayed for the rest of my career.”

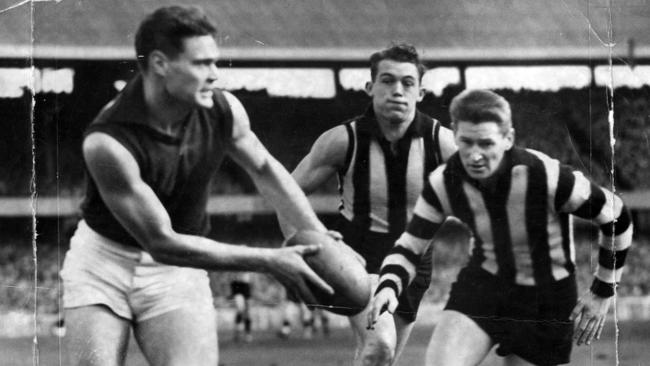

After Barassi experienced the biggest stage in 1954, playing in Melbourne’s losing grand final side against Footscray, he announced himself as a big-game player, kicking three goals as one of the best on the ground, in Melbourne’s 1956 premiership triumph over Collingwood in front of a crowd of 115,902 at the MCG.

“I’ll never forget the roar of the crowd,” Barassi said of the magical moment.

“This was the first time more than 100,000 had attended a Grand Final.”

Barassi’s career flourished under Smith, winning six premierships, two best and fairests, two club goalkicking awards and playing five years as captain.

His 204th and final game for Melbourne came in the winning 1964 grand final.

Little did Demons fans know that it would spark a 57-year premiership drought and lead to

one of the biggest transfer shocks in the game’s history in December 1964 when Carlton appointed Barassi as its playing coach.

Melbourne supporters were reduced to tears, including one Demons fan who had trained her parrot to say, “C’mon Ron”.

“At the time I was so focused on the job ahead of me that I probably didn’t appreciate how my leaving Melbourne may have affected some people,” Barassi recalled.

“I changed my mind a few times about the move. It was tough, but it turned out to be the best football decision I ever made.”

The great Jack Dyer wrote at the time: “Barassi was so much Melbourne that we all believed it wasn’t a guernsey he wore, (it was) just the colour of his skin.”

Barassi excelled as a coach and will forever live in Carlton folklore after masterminding an impossible win in the 1970 Grand Final against Collingwood.

The Magpies held a 44-point halftime lead, but Barassi’s order to handball at all costs followed by a string or revolutionary moves inspired an improbable comeback and win.

Former Carlton player John Goold told the Herald Sun years later that Barassi had sowed the seeds for the faster style of play against Hawthorn in round 20 of the same year by asking us “to handball more than usual”.

The Carlton players quickly embraced the handball concept in the grand final shooting off 40 in the second half, 26 more than Collingwood. There is no doubt it helped turn the game

Goold remembered “a super calm Ron replaced the ranting one”.

“He asked the match committee and committee men to leave the room which just left Ron and us. He hardly raised his voice,” recalled Goold.

“He was positive at all times and explained to us we were going to start a new game with a new team.”

The new team included Vin Waite moving to centre half-back, David McKay to a back pocket, Goold to a wing, Phillip Pinnell to half-back and, of course, 19th man Ted Hopkins to replace Bert Thornley.

Goold said the last move took real guts: “People don’t understand it now, but you couldn’t bring a player back on the ground once he had been replaced by one of the two reserves, so had we got an injury we would have been in all sorts.

“But that was Barassi, a brave coach for a desperate time.”

Goold said Barassi had created a unique spirit among the Carlton playing group.

“Ron would regularly drive miles from his home before work to drag (ruckman Peter) Jones out of bed and take him for a run at St Kilda beach,” Goold explained.

“So when the s**t hit the fan at halftime, we believed in him because we had seen the sacrifices he’d made.”

When Barassi took on the coaching role at North Melbourne in 1973, the game’s greater TV exposure further enhanced his reputation as a firebrand.

He banned chest marks at training as a “stupid waste of time” and was tougher on his team’s champions because he believed being born with natural ability was just luck and “you can’t respect luck but you can respect effort”.

He acknowledged that his methods could have been seen as bullying from the outside but never apologised for being tough on players in a “tough, unforgiving game”.

“How can you expect your players to take on a ferocious opponent who is willing to do absolutely anything to beat you and grind you into the dirt, if you go easy on them?” he said.

He led the Kangaroos to their historic first premiership in 1975 and after drawing the 1977 grand final with Collingwood rallied his troops to win the rematch the following week.

Barassi could not recreate the magic when he returned to Melbourne under much fanfare as coach in 1981, spending five years in charge without success.

He also had a stint with Sydney between 1993-1995 in a move that brought greater attention to the club.

But for the man who is survived by wife Cherryl and children Susan, Richard and Ron, the legend had long since been set in stone.

“I sign my name ‘Ron Barassi 17 4 10’,” he once said.

“The digits refer to the 17 Grand Finals I contested as both a player and a coach

(hence the figure ‘4’) for 10 premierships (a record he shared with his mentor,

Norm Smith).

“People might think that’s egotistical, but I’m unashamedly proud of it.

“It’s spooky when you consider that 17 plus four plus 10 equals 31.”

The famous signature never changed, but Barassi could have been excused for one last addition – bumping the “17 4 10” up to “18 4 11” for the one more Melbourne premiership he had always dreamt of seeing before he died.