Tiwi Islands community Pirlangimpi has produced three Norm Smith Medallists

THIS small island community with a population of 370 souls has produced three Norm Smith Medallists. Welcome to Pirlangimpi: a village of sporting stars.

AFL

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IT is remarkable that the Tiwi Islands, 15 minutes by light plane north of Darwin, with a population of around 3600, have produced three Norm Smith Medallists. But there’s a more incredible stat.

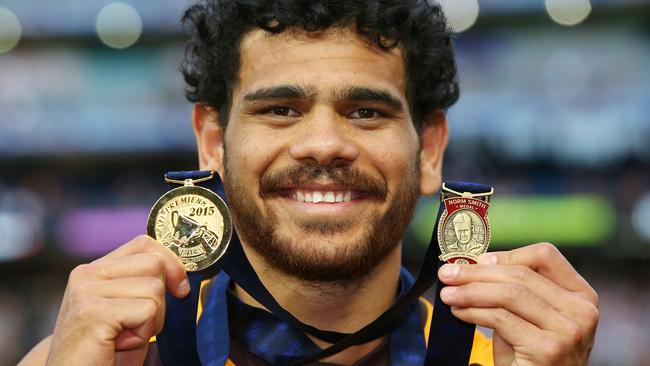

Those Tiwi players awarded best on ground in a grand final - Maurice Rioli, Michael Long and now, Cyril “Junior Boy” Rioli - are tied by birthright to Pirlangimpi, or Garden Point, a beautiful, remote speck of northern Australia compromising just 370 souls.

You’d have to search far and wide across the world to find a higher ratio of athletic prowess to population. This is a village of stars.

For some, Pirlangimpi is a place born of sadness. But that has been overcome with pride for the way its players have changed the game — and the way Australia sees itself.

The Tiwis are two sizeable islands: Bathurst and Melville, separated by the Apsley Strait. Melville is the bigger, and less populated.

In 1941, Pirlangimpi, on Melville Island, was known as Garden Point Mission.

It is where the Catholic Church placed so-called Catholic “half-caste” children from the Kahlin Compound, in Darwin, The Bungalow, in Alice Springs, and elsewhere, to be raised by Missionaries of the Sacred Heart.

These children were the Stolen Generations. Incorrect mission records from 1946 identify 11-year-old Cyril Rioli as a “half-caste” from Alice Springs. His parents are not named.

The same records also name a nine-year-old John (Jack) Long, from Pine Creek, south of Darwin. Only his Aboriginal mother is named.

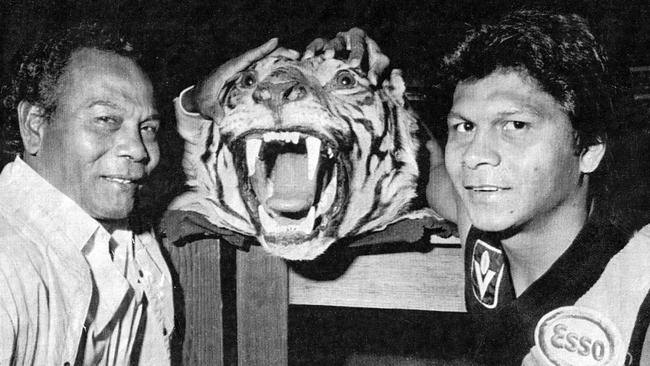

These men, still with us, are the respective fathers of Maurice Rioli and Michael Long, and the grandfathers to Hawks’ star Junior Boy Rioli.

Cyril Sr, 81, who lives at Pirlangimpi with his wife Helena, says the mission records are wrong. He was born on Bathurst Island to a Tiwi woman, who had a relationship with a pearler — possibly Makassan or Malay.

Cyril Sr was classified a “half-caste” and sent the short distance across to Garden Point under the removal laws of the day.

Both Michael Long’s parents were raised on the mission. His father Jack was taken from Ti Tree north of Alice Springs, and his mother, who died when Michael was 14, was taken from Daly River, south of Darwin.

“My dad, he’ll talk about the past with sadness,” says Kathy Long, the mother of Junior Boy and sister to Michael (plus six other brothers). “But most of the times were happy times.”

Pirlangimpi has produced more than the three ‘Norms’. There’s Ronnie Burns, who played for Geelong; Maurice’s brothers Sibby, Cyril Jr (father of Junior Boy) and Willie, who all played for South Fremantle; plus Sibby’s son Dean, for Essendon. And there’s more to come.

It’s not in the water. It’s in the blood. Which means family.

“It’s a special place,” says Kathy. “It is very close-knit. Everyone knows each other, everyone’s related. Doesn’t matter who it is. Everyone’s looking out for everyone’s kids.

“It is a special place because that’s where my mum and dad grew up, and both Junior’s grandparents.”

It must be special.

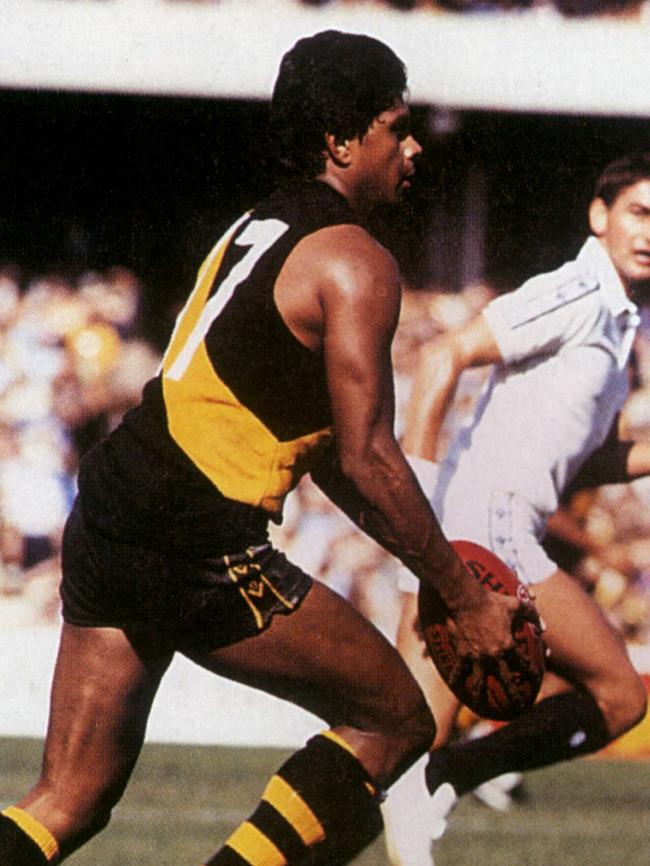

Maurice Rioli became the first player to win best on ground in a losing grand final, playing for Richmond in 1982. He was born and is buried here, dying too young at 53 from a heart attack.

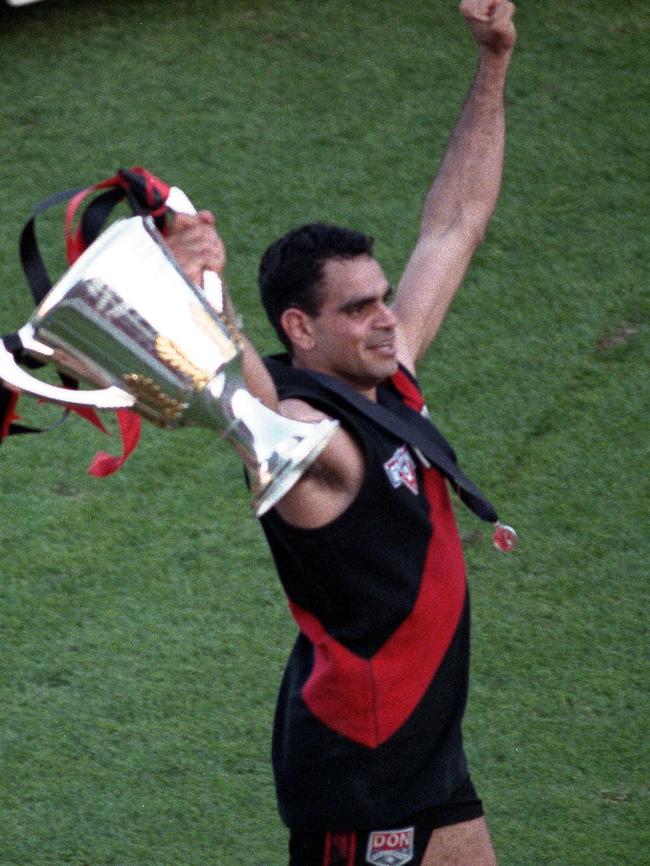

His first cousin, Michael Long, won the Norm Smith for Essendon in 1993. His refusal to tolerate racial vilification awoke a thoughtless nation.

And there’s Cyril, nephew to Maurice and Michael, who last weekend instigated the Eagles’ nightmare by kicking two first-term goals followed by an infuriating game of unremitting interference that broke their resolve.

Cyril, 26, wasn’t born when uncle Maurice won the Norm Smith, and was only four when uncle Michael won his. But he was raised in the same Tiwi football world.

“Just watching my dad and having seven brothers and seeing how competitive they were, everything was pretty much eat, sleep and live for footy,” says Kathy.

Kathy took Junior Boy home to live in Pirlangimpi from the age of five. By then the Catholic mission was gone, replaced by a state school with unusually high attendances for an indigenous community.

“We had some teachers that really pushed the kids to be a part of sports. Junior was lucky because his dad was playing footy. He’d go in and play footy for the Saints’ (Darwin’s St Mary’s) juniors.”

She remembers Junior Boy as good at “playing” with other kids, but knew something was up when he was picked to run a 200m dash for a Tiwi side at a Darwin comp.

“He didn’t know how to run,” she says. “He left them behind by about 100m. Someone come up to me and said, ‘Your son has just beaten the NT champion.’ He was about nine.”

AS the southern game shuts down for summer, the NT football season is just beginning. Willie Rioli, coach of the Tiwi Bombers, the islands’ Essendon-linked team that plays in the Northern Territory Football League, is getting organised.

Willie, 43, the youngest son of Cyril Sr, says football was all he knew as a kid.

“I thought Aussie Rules was the only sport people played,” he says.

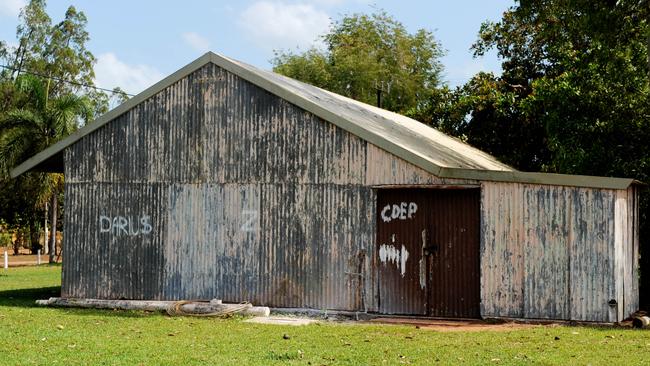

Pirlangimpi’s dusty oval is eaten down by wild horses, but the rains are coming and the new grass will soon welcome the town’s only team, the Imalu Tigers, who play in the local Tiwi comp.

Willie can’t explain what it is about Pirlangimpi and football stars. “Some people work harder, and some get the chance,” he says.

“It’s no different to anywhere else. But everybody has a dream. It’s a matter of putting it into action. I was a big dreamer of footy and I think that matters.”

He often tells his Bombers to remember the Tiwi legends. There’s his older brothers, Maurice, and Sibby, who also died too young and is buried alongside Maurice in the community.

And there’s David Kantilla. Recruited to the SANFL in 1961, he was the first traditional Aboriginal man ever to play in a southern league.

“David was an inspiration for us,” Willie says. “I didn’t get the chance to meet him or see him play, but it took a whole lot of courage for him to go south, especially in those times.”

Kantilla loved football but hated being away from the Tiwi Islands. The same homesickness has plagued many young indigenous footballers who’ve journeyed south — Junior Boy included.

At 14, Junior Boy was attracting attention with the St Mary’s juniors in Darwin. He and a cousin, Steven, were chosen for a scholarship-boarding program at Melbourne’s Scotch College, overseen by teacher Rob Smith.

“They wanted to select some indigenous boys to go away — they were guinea pigs,” says mum Kathy.

Cousin Steven went home from Melbourne in a hurry. “And Cyril stayed,” says Kathy. “That was a bit hard, he wanted to come home. He didn’t want to be there by himself. We talked him into it, a bit of tough love there.”

At first, says Kathy, they asked Rob Smith to watch him closely. “Junior would go and see him every day. We just focused on getting through the first 10 weeks, and then the next 10, taking it in stages.

“I’d ring Rob and one day he said, ‘I don’t see him that much any more.’ It worked.”

Some like to argue that the Stolen Generations were for the best. This presumption, made by people who never lived through it, insults those that did. Every story is different. No political outcome ever outranks personal experience.

And yet the children of Garden Point have mostly positive memories of the priests, brothers and nuns who raised boys and girls in separate dorms.

“They were good people,” says Cyril Sr. “I can’t complain about one — not a bad word.”

He “can’t exactly pinpoint” why this place has produced so many good footballers, but says it has something to do with the way missionaries taught them. “If you’re not brought up the right way, you won’t get any place,” he says.

Legend has it that MSC Brother John Pye, who arrived on Bathurst Island in 1941, introduced the “modern” game to the Tiwis who, according to one version of history, “played a traditional form of football, whose object was to run or kick the ball over a line.”

Cyril Sr says the boys already knew the game backwards. What Brother Pye did was start an inter-Tiwi comp that included Garden Point, which — albeit interrupted by an evacuation of kids during War II — was starting to fill with Stolen kids.

Cyril Sr played with the great David Kantilla, but says there were another 20 Tiwi players as good as him. And Cyril Sr could kick with both feet, decades before it became a mandatory skill. “We just went for it,” he says. “We got stuck in.”

Cyril Sr spoke to his grandson on the Tuesday before the grand final. “I told him when he played in the 2008 grand final he was very good. I told him that this year he should win the Norm Smith. He’d played well all year and it was time.”

He doesn’t think of comparing his son Maurice to his grandson, but — seeing as he’s asked — he says: “Junior’s a little bit ahead. He’s played more (AFL) games.”

He sees them as alike in temperament. “Cyril is there to chase the red ball for his club. That’s it. I can’t remember him losing his temper. My son was like that. All my boys were like that.”

Cyril Sr has in recent years changed his surname to Kalippa — his traditional name. The nuns gave him “Rioli” because a surname was needed for documents. He has no idea where it came from and says: “I don’t like it.”

It is his only issue with the mission times — and he’s corrected it by deed poll. His issue with football in these times is that it’s become “like rugby. Too much scrambling, with 25 players around the ball.”

Former Territory politician Marion Scrymgour’s mother was raised on the mission and, as a child, Marion did not even know she had older sisters because her mother was not allowed to keep them.

She says some mission kids who were taken to Garden Point from the mainland, with no Tiwi heritage, felt lost when they’d finished school. They were turned loose, making their way to Darwin.

But, disconnected from their own people, they’d come to love the place. And the Tiwi people made sure they felt they belonged.

“The history of the Stolen Generations hangs over Garden Point,” says Marion, “but many years ago the Tiwis made a decision to allow mission families to go back to the island and live there.

“So, whilst there’s sadness, there’s great joy. These islands are special. It’s home. They’re our people. It has issues like every other place, but the Tiwis have always been isolated from the mainland. It’s a pretty good life.”

And good football, says Marion: “Seems to be in that gene. Michael Long was as special as Maurice. And young Cyril is the combination of the Rioli and the Long blood.

“I can’t wait to see young Maurice’s son, Maurice Jr, who looks exactly like Maurice. He’s one for the future.” He’s only 11 or 12, at school in Pirlangimpi, but Marion says: “He’s a special little footballer.”

If that’s a weight of expectation for small shoulders, Tiwi footballers have shown they can stand it.

Willie Rioli says if his small community’s influence is outsized, so is the goodwill coming back from the mainland. “The Australian public has been fantastic,” says Willie. “We hope it continues.”

Kathy Long says she was on Facebook when her son was playing the Dockers in the preliminary final. “Someone I call my son sent me a message, saying: ‘I want to be like Cyril.’

“I laughed to myself. I thought, ‘You can!’”