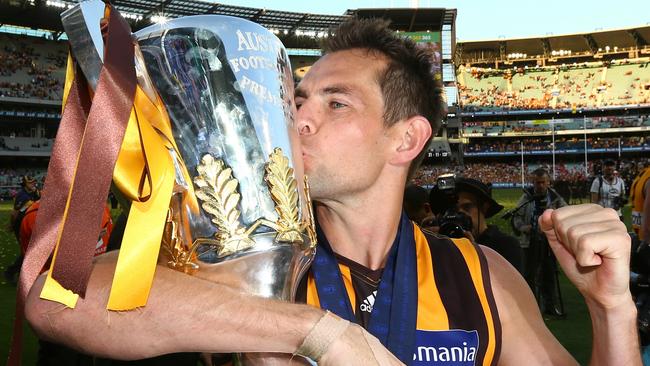

How Luke Hodge went from a fat kid to a Hawthorn premiership star

AT a young age Luke Hodge was a fat kid who no one wanted on their team but the Hawthorn champ reveals the sacrifices he made that helped him become a four-time premiership star. READ THE BOOK EXTRACT

Hawthorn

Don't miss out on the headlines from Hawthorn. Followed categories will be added to My News.

FROM being the fat kid no one wanted on their team, four-time premiership star Luke Hodge has forged a remarkable career.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I hated it. The teams would be picked and I’d be left out. No one wanted the fat kid. Often it was because we’d played footy earlier and, given I was bigger than the rest, I’d easily beaten them or I might have roughed them up. So to get back at me they wouldn’t pick me the next time.

They called me fat, so I called them a sook if they started crying.

“Bad luck, fat boy,’’ they’d say. I didn’t know why I was bigger than everyone else — I liked food, but I figured everyone else did too.

I’d been given the nickname Pumbaa, after the warthog from The Lion King movie, and it was one of those that stuck.

The teasing would get worse on the school bus. I normally tried to give back as good as I got, but sometimes my brave face would break and I’d come home in tears. Mum was the only one who would see them. The way I dealt with this was the way I dealt with everything — I grabbed my footy.

SON OF LEGEND: MAURICE JR ALREADY HAS ‘RIOLI’ TRAITS

2018 FIXTURE: WHAT WE KNOW SO FAR

STEVIE J: CATS SACKING WAS EMBARRASSING

One of Dad’s many theories when it came to football was that good players needed to be able to kick on both feet. I was a natural left-footer and would spend most of my time at the Western Oval in Colac practising snaps and torpedoes.

Dad would make me kick on my right. He’d want 10 on the right foot and all had to hit the target.

Being the sort of kid I was, I would try to get away with doing all my kicking on my left. Things would inevitably turn sour when it was time to leave.

“There’s your footy — go and kick it by yourself. I’m going home,’’ he’d say.

Some nights I’d chase after him, kicking the ball with my right foot; on others I’d crack it and sit in the middle of the oval in tears.

There was a stubbornness about the Hodges. It started at the top and had worked its way down.

An opportunity to try out for the Victorian primary school football team came up, and given that I was a lot bigger than most kids, Dad and I went up to Melbourne for a look.

We travelled to Windy Hill for the trial. There were hundreds of kids there and we ended up having to go back several Sundays in a row.

Fortunately, I made the final cut. Not bad for a fat kid. Getting a Big V jumper was pretty cool.

THE SACRIFICE

“WHAT the hell are you doing?’’ I’d seen my father angry before, but nothing like this. He grabbed me and pinned me against the wall.

I managed to say: ‘‘I got home a bit late.’’

‘‘Why didn’t you call? You have a phone, use it.’’

I’d been to the Colac Tech School ball and had told Dad I’d be home at midnight. I was playing for Geelong Falcons the next day in Tasmania. The problem was that it was now past 2am. And an even bigger problem was about to rear its head.

‘‘Did you drink?’’ Dad had been adamant that I wasn’t to touch a drop of alcohol the night before a game of football. I remember I’d waved to him as I walked out the door, offering: ‘‘No problems.’’

There were problems now — big problems. We’d all met at Mum’s house to get dressed and then we’d caught a stretch limousine to the ball. Champagne went around in the limo and I had a couple of glasses, plus a beer or two. When I got home I wasn’t drunk by any stretch, but neither was I in any position to argue my way out of this.

“I had a couple,’’ I said. It was getting more and more uncomfortable.

“If I say you’re not going to drink, you don’t drink!’’ he yelled. ‘‘If you drink the day before a game again, you won’t play.’’

With that, he let go. I was in shock, which soon turned to anger.

While I resented him for how he’d reacted, as time went by I started to get an understanding of why he’d done it. He wanted me to realise I had an opportunity that my mates didn’t have.

I was playing in the TAC Cup, which was the first step towards getting drafted. I wanted to play AFL and the message Dad was sending was simple: Don’t blow it.

KOKODA

If you’re talking about eye-opening experiences, nothing comes close to Alastair Clarkson’s choice of pre-season camp: the famous Kokoda Track.

For five days, we hiked for 12 hours a day in 33-degree heat and 95 per cent humidity. The amount of sweat that came out of our bodies was exceptional — guys were drinking up to 12 litres of water on the hike without requiring a toilet stop as the water just evaporated in sweat.

We were allocated basic rations, which included nuts, instant soup, pasta, noodles, canned fruit and protein bars.

The lack of sleep and lack of food combined with the obstacles placed in our way really tested us. We had to carry logs and stretchers with 60kg sandbags on them to replicate the weight the soldiers had carried 60 years earlier.

For Clarko, the challenge was to see who would fold, who would be selfish and who would help their teammates. A brilliant example of the latter was produced by Trent Croad. Some of the steps we had to navigate were three-quarters of a metre high and we were all carrying a 20kg backpack and a 20kg sandbag.

Harry Miller was a small indigenous kid and he was almost falling backwards as he tried to get up the steps. Croady intervened, took Harry’s sandbag off him, connected it to his own and then helped push his teammate up the steps. That was the type of leadership Clarko wanted to see.

We went into the trip as a loose collection of new and old players with a new coach; we returned different people.

KILLING THE SHARK

“What happens if sharks can’t go forward?’’

Clarko was standing at the front of the coach’s room in the bowels of the MCG. On the whiteboard he’d drawn a picture of a shark. We were less than an hour away from running out onto the ground for the 2008 Grand Final.

‘‘They die,’’ someone said.

‘‘That’s right,’’ Clarko said. ‘‘Sharks need forward momentum. Sharks die if they get caught in a net, because there is no water and oxygen running over their gills. So as soon as they stop, they die.

‘‘What has that got to do with this? They’re trying to come through us like a shark. Well, good luck to them. Good luck to them in the Grand Final, on the big stage with lots of pressure. They’re coming up against the best defensive pressure side in the competition.’’

He started tapping at the whiteboard.

‘‘We have to kill this shark as early as we possibly can, because if it sits there, it’s just going to die.’’

He was saying the key was to deny Geelong the centre corridor and force them wide.

Clarko’s cluster had been invented for this day.

‘‘Let’s kill the f---ing shark,’’ he said. And with that, the meeting was finished. The coach had done his work. It was now time for the players to do theirs.

THE CAPTAINCY

“I want to be captain.’’ It was the first time I’d said it out loud. Brad Sewell had asked the question and I didn’t think I needed to hide my aspirations.

‘‘Well, keep going along these lines,’’ he told me. ‘‘The boys are starting to see a real change in you.’’

He then added the money line. ‘‘The senior guys are starting to have faith in you.’’

Boom. There it was.

The captaincy handover was made official by Jeff Kennett (at the best-and- fairest) and I managed to win my second Peter Crimmins Medal. This was classified as a double celebration. Lauren and I found ourselves with a few teammates and friends from Colac in Crown casino’s Mahogany Room.

There was a dispute over daylight saving — the clocks were changing and we were trying to figure out if they were going forwards or backwards an hour. The reason for this was because we had to be at St Kilda Beach at 5am.

I struggled to get out of my suit in the darkness on the beach. Some of the boys had been home and even had a couple of hours of sleep, and were there in their bathers. I was in my jocks.

We all jumped off the pier into the freezing water and somehow swam back to the shore.

‘‘Hodgey, do you want to address the boys?’’ Clarko asked.

‘‘Of course not, coach,’’ is what I wanted to say. I was pretty sure I wouldn’t make any sense.

But I began with: ‘‘Look, boys, it’s not good enough.’’

That was the gist of what I attempted to say, but my slurred speech meant it didn’t exactly hit the mark.

Later I realised the session hadn’t been without incident. I’d lost my wedding ring during the swim and also managed to misplace my wallet and watch.

If I had been in better shape, my speech for Clarko would have been gold.

‘‘When you appointed me, you said I was captain for a reason and it was important that I didn’t change. You said if I wanted to have a beer with the boys, I should have a beer. You said, ‘Don’t change, because that’s why they’ve voted you in’.

Well, coach, I’ve followed your advice to the letter.’’

Edited extract from The General by Luke Hodge, published by Penguin Random House Australia, RRP $45, on sale Monday October 30.

Be one of the first 200 readers to buy The General for $37, and receive a copy signed by Luke Hodge. Order online at heraldsun.com.au/shop or call 1300 306 107.