Scott Pendlebury through the eyes of his three coaches: Mick Malthouse, Nathan Buckley and Craig McRae ahead of 400 games

Scott Pendlebury’s career changed in 2006. Now, the ‘conductor of the orchestra’ is Collingwood’s greatest ever player. GLENN McFARLANE speaks to Pendlebury’s coaches about the 400-gamer.

AFL

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It was 2006 and Scott Pendlebury’s name on Williamstown’s magnet board – and his footy career – were about to be flipped.

The 18-year-old convert from basketball had been biding his time in the second tier VFL since recovering from a bout of glandular fever that hampered his first AFL pre-season.

Having been drafted as pick five in the previous year’s national draft, just three selections behind Dale Thomas, Pendlebury spent the early part of this Williamstown game – one of 10 matches played for Collingwood’s then VFL-affiliate – running the expanses of the wing.

That was about to change forever.

In the middle of a huddle during a break in play, Collingwood coach Mick Malthouse strode purposefully over to the coaching magnet board, grabbed Pendlebury’s name off the wing and placed it with impact in the midfield.

“He (Malthouse) just threw Pendles’ name from a wing to the middle and said: ‘You’re not a wingman or a flanker, and you’ll never be’,” said someone who witnessed it that day.

Almost two decades on, Malthouse recalled the moment, if not much else about the match.

He had seen enough of Pendlebury to deduce blistering pace wasn’t going to be his strong suit, but he knew instantly that he had the peripheral vision and talent to be an elite midfielder.

“I didn’t think he had the leg speed to play outside,” Malthouse said this week. “I remember thinking he was not having an impact (in the game), so I thought ‘let’s put him in the midfield where the action is’. He just had elite decision-making capabilities.

“He was 18 and coming off a basketball background and normally you put those kids out on a wing. But once you saw him out there, you could see he wasn’t going to get touched (in close) as he had this beautiful peripheral vision.”

In a matter of weeks Pendlebury was promoted to the seniors. He didn’t look back and has never played a VFL game since his 2006 debut season.

It wasn’t the only change Malthouse made at the time. Thomas had been playing half-forward with a few midfield cameos in the seniors at the time, but he was on the move, too.

“I thought they (Pendlebury and Thomas) were tailor made for swapping,” he said.

“‘Daisy’ (Thomas) was playing a bit of half-forward, but he went out to the wing after that.”

Within four years, Pendlebury won a Norm Smith Medal as a star midfielder and Thomas became one of the AFL’s best wingmen.

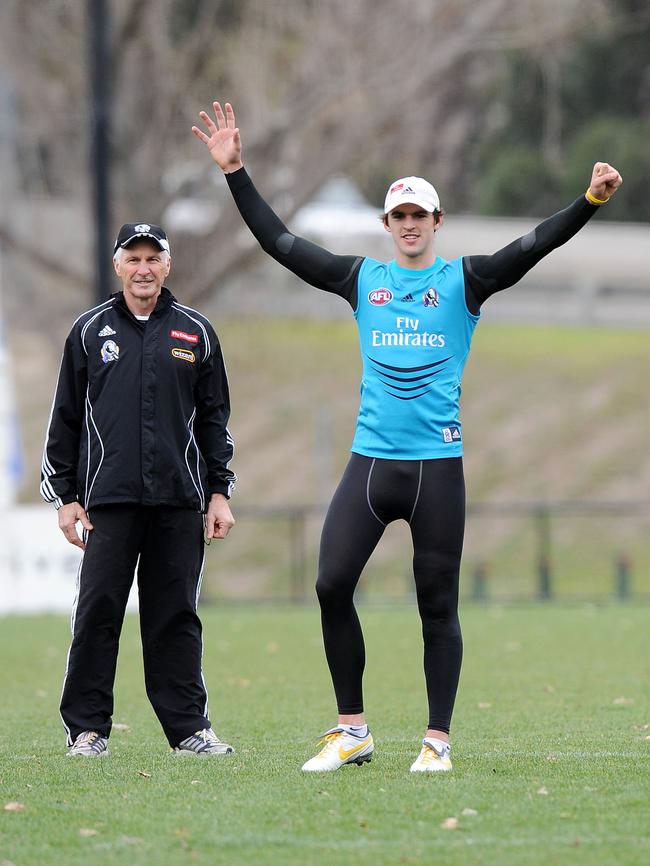

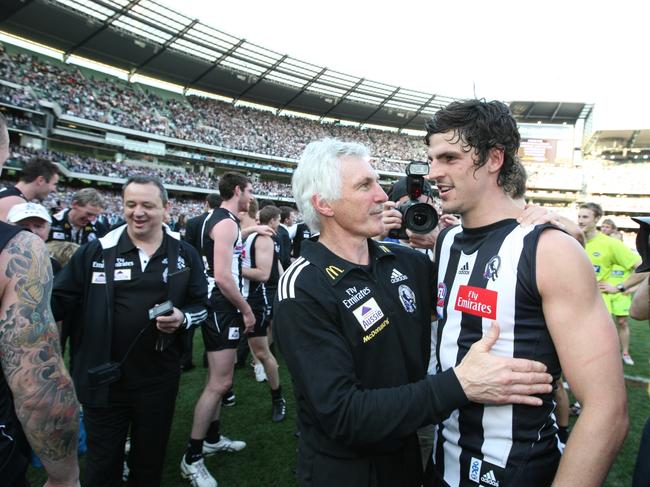

Malthouse is connected to the first player, and soon to be sixth player, to reach the 400-game milestone.

He played alongside Richmond’s Kevin Bartlett, and coached Pendlebury in 127 of his 400 matches.

“When you look at the 400-game players, Pendles is unique,” Malthouse said. “You look at Bartlett, (Michael) Tuck, (Dustin) Fletcher, (Brent) Harvey and (Shaun) Burgoyne and they have two things in common – they rarely got injured and they all had speed.

“Pendles has been injured, but nothing too bad, but he is not quick. But he is very quick of mind. He has not lost his ability (over the years) and he still pulls it (the game) back to his own speed.”

‘YOU WON’T FIND PENDLES PLAYING PING PONG’

Nathan Buckley reckons there is a reason why Scott Pendlebury has been elite at most of the endeavours he undertakes.

His former coach says with a smile: “Pendles doesn’t care for the things that he can’t win … he won’t engage in anything that he doesn’t have the upper hand in.

“That’s why you will never see him on a table tennis table. He is one of the worst table tennis players I have ever seen.”

Buckley said Pendlebury was good at most things he turned his hand to, but had little time for the pursuits that don’t float his boat.

“The only time I have seen him take a shortcut was when the boys would line up for some warm-up strides,” Buckley said. “He would always somehow find his way to start half a second before the whistle went off, and he would just keep going.

“Pendles was never the fastest. Try as he might, he never really picked up his 10 or 20m time … the way he was able to (keep) up with everyone was to start before they did. He did it mainly because he knew it would annoy the blokes around him.”

Buckley and Pendlebury formed a great coach and captain partnership across almost a decade. The admiration was mutual.

But when Buckley, the player, was asked in 2006 to describe Pendlebury in his debut year, he used one word: “aloof.”

“Alan Richardson was (Collingwood’s) head of development in 2006 and he went around looking for the leaders of the organisation asking them for a word to describe all the young blokes,” Buckley said.

“Mine for Pendles was aloof.”

He soon came to realise the kid from Sale was more observant than aloof.

“What I witnessed was a guy who was a bit stand-offish. He would always sit back and observe and it looked like he wasn’t super engaged,” Buckley said.

“But what soon became apparent was that he was analysing everyone and everything.

“The culture was still old school, so he probably didn’t waste his time in his early years listening to too many others … as they probably wouldn’t listen to him.”

Buckley said Pendlebury’s stubbornness and strong-will helped to make him the player and leader he ended up being.

“The thing you could say about Pendles, and probably all of the greats, is that they do it their own way,” he said. “There is a strength of character and a resolve, they believe in their methods and processes. They are unshakeable through the inevitable ups and downs.

“He went through a period there (in the mid to late 2010s) where he would just move his name tag at the start of the second quarter. He would want to give himself a little extra second-quarter break, to sit on the pine for the first rotation.

“It happened four or five weeks in a row and I would say to him: ‘Why don’t you share it with us, so at least we can plan around it rather than you just moving your name tag from the middle of the ground to the bench.”

In a way, he’s still marching to his own beat.

Buckley had a chuckle last week when Pendlebury tried to crib a few extra minutes when the Magpies decided to sub him out at three-quarter-time against Richmond to ensure he was right for his 400th outing.

“In his 399th last week, when he was tapped on the shoulder and subbed out, he was still walking towards the centre bounce at the start of the last quarter,” Buckley said.

“He would have been thinking, ‘I want to play another five minutes’ … (before he was told) ‘We need you off now’.”

COLOURING BOOKS TO GRAND FINAL ’CONDUCTOR’

Craig McRae has seen two Scott Pendlebury versions – the fiercely driven, meticulous young gun who didn’t like to be distracted and the father equally driven but who now revels in having his kids close at hand.

The Collingwood coach doesn’t know what a young Pendles would have made of a teammate bringing his kid into team meetings a decade or more ago.

The man himself now does it weekly.

“What people don’t see (from the outside) is the family stuff,” McRae said.

“I didn’t see it last time I was here at Collingwood (as head of development, where he started in late 2010). I saw a really driven, somewhat selfish individual who was meticulous about ‘why I need to do this many reps’.

“Now I am seeing a player who knows everything he needs to prepare well and perform, but one who has a balance of family.

“It’s about his connection to his wife (Alex) and kids (son Jax and daughter Darcy).

“Pendles comes into the team meetings with his kid Jax … his boy is doing the colouring in as we are having the team meetings.”

It’s an image that takes place inside the AIA Centre most weeks and always brings a smile to McRae’s face.

The Magpies coach also recounted this week the eye contact he had with Pendlebury in the frantic final moments of last year’s grand final.

Brisbane’s Charlie Cameron had just goaled to put his team in front 18 minutes and 50 seconds into the final term. A seesawing game was going right to the wire.

McRae recalled: “As soon as Cameron kicked the goal, he (Pendlebury) was looking over at the bench and I’m looking back at him. I am pointing at the sign we had up at the time.”

Ten months on, the coach is reluctant to reveal what the sign meant. But he stressed it denoted “a method and a system that gets all the players and the team on the same page”.

Pendlebury was at the heart of the message.

McRae said: “He (Pendlebury) is the conductor of the orchestra. You go to the conductor to say ‘this is the song we are playing’ and he goes and executes it.

“If you go back and watch it, he is looking around, making sure everyone is organised and ready to go at the next bounce. That sort of thing filters through to the entire group.”

Young midfield star Nick Daicos was preparing to head out of the centre square before the next bounce, believing it was his turn to rotate out.

But the conductor in black and white never let it happen. Pendlebury shouted to Daicos above the roar of the crowd: “Mate, do you want to be a part of this?”

In one of the most famous passages of play in Collingwood’s history, Daicos stayed in the midfield for the bounce, released a nifty handball to Pendlebury who kicked into attack. The ball bobbled out to Daicos who handballed to Jordan De Goey who drilled a crucial goal.

“He helps set it up, he executes it and he looks back at me again,” McRae said of Pendlebury’s part in the Magpies’ symphony.

“I kept the same sign up. I said, ‘We are going again’. He (Pendlebury) questioned it, put his hands up and said: ‘Are you sure?’ I said: ‘Yeah, we’re going for it.”

The Magpies kicked the next goal via Steele Sidebottom before a late major to Joe Daniher brought the margin back to four points at the end in one of the most remarkable grand finals.

“Pendles just went into complete beast mode in the last quarter of the grand final,” McRae said. “All those years of experience, all that driving of others came down to that moment on the biggest stage when it mattered most.

“He was just delivering at his optimum again.”